Document of the Month 12/24: A Lost Arabic Papyrus

From Jerusalem To New York:

The Journeyings and Insights of a Lost Arabic Papyrus, P. Mird Ar. 102

by Robert Hoyland

The whereabouts of the Arabic document that is the subject of this post is still a mystery. Sometime in the eighth century CE it was deposited, along with a couple of hundred other Arabic papyri, in a cave on top of a mountain in the Judaean desert, a short distance to the south of a large and imposing monastery. When you are on this isolated peak, it feels like you are in the middle of nowhere, for you are surrounded by rocky desert and arid valleys (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Aerial drone photograph of the Kastellion/Khirbet Mird Monastery with arrows indicating the two most likely contenders for the cave that contained the papyri. © Hyrcania Fortress Excavation Project.

Yet only 6 miles to the east, as the crow flies, is the Dead Sea with its many thriving agricultural communities, and 10 miles westwards lies the historic town of Bethlehem, with Jerusalem then only a short hop to the north. The monastery is a reconstructed Herodian castle, and this explains its name: Kastellion in Greek and Marda in Syriac, both implying a fort, and from the Syriac comes the modern Arabic name of Khirbet/“Ruin of” Mird.

Map showing the location of Khirbet Mird in the Judaean Desert, known in Greek as Kastellion. ©Robert Hoyland.

For three centuries, from around 500-800 CE, monks bustled about their business on this dramatic mountaintop retreat, in contact with the many other cenobitic centers in this narrow strip of desert between the Judaean hills and the Jordan valley. A partial record of their lives is to be found in the corpus of Greek and Christian Palestinian Aramaic papyri stored in the same cave as the Arabic documents that I have just mentioned. Alongside the numerous Biblical and liturgical texts, the corpus comprises letters, legal documents, accounts, and even a few literary pieces, such as a fragment of Book One of the Iliad, which likely served as a tool for teaching Greek. These are all to be expected in a monastic library, but it is not so easy to guess why the Arabic texts are there, especially as many of them are obviously Muslim documents: correspondence between Muslims, including senior Muslim officials, Qurʾan fragments, and even an extract from the Prophet Muḥammad’s biography. I will return to this question but let us now look at the circumstances of the discovery of these papyri more than 1100 years after their deposition.

The unearthing of scrolls at Qumran at the northern end of the Dead Sea in 1947 led to a flurry of activity in this region as Bedouins, soldiers and scholars ran from cave to cave in a frenzied search for more precious fragments. Members of the Taʿamirah tribe, who had long inhabited land between Bethlehem and the Dead Sea, came upon a cache of Greek, Aramaic and Arabic papyri, which they then sold to the Palestine Archaeological Museum in July 1952. A French Dominican priest named Roland de Vaux, who was excavating at Qumran, got wind of this discovery, and he contacted Philippe Lippens at Louvain University in Belgium, urging him to organize a rescue mission. This Lippens did and from February to April of 1953 a small Belgian team undertook exploratory work at Khirbet Mird. Some roamed around the wadis hunting for more documents, while Robert de Langhe stayed at Khirbet Mird, supervising seven Taʿamirah Bedouin as they cleared out earth and rubble from the cave where they had found the first lot of papyri. In the course of this excavation many more fragments were brought to light. At the end of the season the spoils were divided: the Greek papyri went to Louvain, while the Aramaic and Arabic texts were housed in Jerusalem, first at the Palestine Archaeological (Rockefeller) Museum, and later, under the charge of the Israel Antiquities Authority, at the Israel Museum, and now at the Schottenstein National Campus. For a long time this corpus attracted very little attention. No catalogue of the Greek texts was published and only a few of them were edited, and the same is true of the Aramaic texts. The Arabic papyri fared better thanks to Adolf Grohmann, who published an edition of 100 of them in 1962, but his work inspired very few scholars to follow his lead, and on a visit to Jerusalem in 2019 I was surprised to find that there were over 400 fragments – presumably Grohmann had only selected the finer texts that caught his eye. Finally, however, the Khirbet Mird papyri are now being conserved and digitised, both in Louvain and Jerusalem, and so there is some hope that they will attract more attention in the future.

But the papyrus that I want to talk about was not one that went to these two cities, but rather to the United States. It was acquired by a certain Commander Elmo Hutchinson during his 1951-54 tour of duty in Israel/Palestine as a military observer with the United National Truce Supervision Organization. On his return to America he wrote to Florence Day, an assistant curator of Islamic Art at the Metropolitan Museum and told her that “prior to leaving I obtained some fairly large pieces of papyrus in Greek, Arabic and Aramaic from the Bedouins living southeast of Jerusalem”, which he had then shown to Gerald Harding, the director of antiquities of Jordan, which held the West Bank at that time, “for photographing and clearance” (letter of 11 May 1955). Miss Day agreed to look at the papyri and after receiving her report he offered them to her for sale, since, as he said, he had no means of properly preserving them. In her letter of June 24, 1955, to Commander Hutchinson she declares that Carl Kraeling of Chicago University would like to buy the Greek papyri, while she would take the Arabic texts, which she describes as “one larger legible piece and three fragments”. It is this larger legible piece that I will talk about here. It is uncertain where it is now. Florence Day said that Hutchinson’s Arabic papyri “will eventually come to this museum, where they will always be kept safely”. However, she was summarily dismissed from her job the next summer, which greatly upset her, as we know from her correspondence with Paul Sachs (d. 1965), businessman and art historian, who acted as her patron for over two decades. This makes it unlikely that she ever gave the papyri to the Metropolitan Museum, and indeed they have no record of it in their collection. From 1958 to 1960 Miss Day was employed by the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard to produce a report on the Islamic art collections in the Boston area as a preliminary move to setting up a “program in Islamic art”. Sadly, she developed health problems soon thereafter and did not work again in the field, and both she and the papyrus disappear from our view. The Rhode Island School of Design owns a few textiles that are stated to be “from the estate of Florence E. Day”, which makes it likely that she also bequeathed Hutchinson’s Arabic papyri to a similar sort of art or educational institution, but this remains to be investigated.

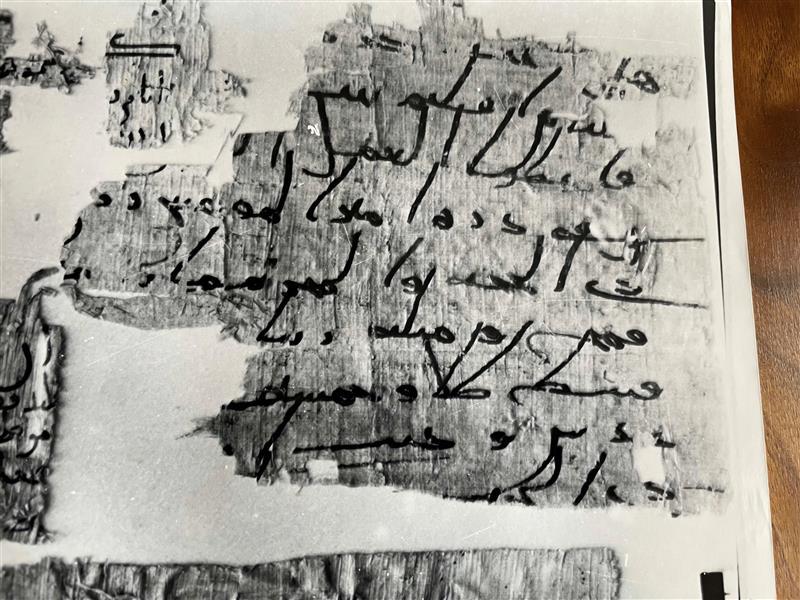

Fortunately for us, these papyri were photographed by Gerald Harding before being carted off to America and the photographs were acquired by Robert Donceel of the Université Catholique de Louvain, whose wife Pauline Donceel-Voûte recently entrusted them to the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven. The “larger legible piece” that Florence Day mentions is particularly interesting (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Photograph of Papyrus P. Mird Ar. 102. KU Leuven archives (courtesy of Eibert Tigchelaar).

It is written in a beautifully clear legible hand of the mid-Umayyad period (ca 690-710), with the ascendant letters rising high and all other letters low and in proportion. The first two lines, which would have contained the invocation (“in the name of God…”/bismillāh…) and the sender, are unfortunately missing, and the text opens with the addressee, which is the people of a village, the name of which is frustratingly unclear. Crucially, though, we learn that it belongs to the jurisdiction of Jerusalem and, more specifically, to a town that begins with Bayt, perhaps Bayt Laḥam (Bethlehem). Lines 5–10 constitute the main part of the document, in which the villagers are instructed to supply the provisions due for the months of Dhū l-Hijja and Muḥarram in the form of wheat, olive oil, grape juice and lentils to the labourers working on the construction of a palace of the “commander of the faithful” (amīr al-muʾminīn), that is, the caliph. Lines 10–11 concern the time of writing and possibly the name of the scribe, but the former is partial, and the latter is absent.

In short, this document is a requisition order, issued by the new rulers of the Middle East to their subjects. The word for “provisions”, rizq (line 6), can be a religious term, then designating the sustenance that God gives to his faithful, but it also has a more mundane sense, referring to the foodstuffs that the conquered peoples had to deliver to the troops of the Muslim Arab government or to those who performed tasks for them. It is very close in format to the requisition orders that survive in the archive of papyri from Nessana in southern Israel/Palestine, dated to the 670s. There is the same demand for two months’ worth of food and the same hierarchy of geographical administration: region (kūra), municipality (iqlīm) and village (qarya). The requisition orders of Nessana speak of the region of Gaza, whereas in our document it is Jerusalem. This answers an old question about whether Jerusalem had an administrative function in the Early Islamic regime; clearly it served as a regional capital of Palestine, on a par with Gaza. Another fascinating aspect of this papyrus is its allusion to the “palace of the commander of the faithful” (line 6). The Arabic word used here for palace is dārat, which also occurs in a sixth-century Greek papyrus from Petra rendered in Greek letters as daraṯ. It is equated in bilingual texts to the Greek word aulē, which can just designate a hall, but also a grand residence (villa, palace). The same Greek term features in several Aphrodito papyri from Egypt that all pertain to the years 86–91/705–710 and also concern the construction of “a palace of the commander of the faithful” (aulē tou amiralmoumnin). The location of this caliphal residence is not named in the Egyptian papyri, and this has given rise to a lively debate over whether it was being built in Fusṭāṭ or in Jerusalem. Moshe Sharon argued strongly that such a project was “beyond the ability of the Umayyads”. Our document offers irrefutable evidence that a royal palace was under construction in Jerusalem, and it suggests that the Aphrodito papyri, which are roughly contemporary with our document, are also referring to a building in Jerusalem. Scholars usually connect this building with the early Islamic complex of structures that lie to the south and west of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem and that were excavated by Benjamin Mazar and others in the 1970s.

So we can see that this document, though short and fragmentary, has a lot to tell us. It might also shed light on why it, and many other Arabic documents along with it, ended up on top of a mountain in the Judaean desert. Plausibly, the village to which it was sent lay to the west of Bethlehem, not far from the mountain-top monastery. One of the Greek papyri mentions a mosque and this could have belonged to this village and served as the repository of all the Arabic texts of Khirbet Mird. Some catastrophe might have prompted the villagers to deposit their archive in a cave by the monastery, which was surely known as a safe and secure spot. This is a lot of conjecture, but one thing is sure: this corpus still has many insights to impart about the daily life of a monastery in the Judaean desert and the beginnings of Muslim government in this region. It takes patience to decipher these fragments, but the real-time data they yield makes the effort worthwhile.

- [بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم]

- [من فلان بن فلان الى] ا

- هل ... ﻣ[ن كورة]

- [اﻳﻟ]يا من اقليم بيت [لحم]

- فاعطوا العمل اﻟ[ذﻳ]ن ...

- ون في درة امير المومنين رزق

- ذي الحجة والمحرم مايه مد[ى]

- قمح ومثله زيتا و ...

- قسط طلا وخمسة ...

- عدس وكتب ... في

- ذي الحجة [من سنة ...]

-

[In the name of God the Merciful the Compassionate]

-

[From so-and-so son of so-and-so to] the

-

People of (the village of) … [from the province (kūra) of]

-

Jerusa[lem] from the municipality (iqlīm) of Beth[lehem]

-

Give the workers w[h]o [are working]

-

on the palace of the commander of the faithful the provisions (rizq)

-

of Dhū l-Ḥijja and Muḥarram: one hundred modii

-

of wheat and the same amount of oil,

-

a kistis (xestēs) of grape juice and five …

-

of lentils. And it was written in

-

Dhū l-Ḥijja [of the year …]

Amitai-Preiss, N., “Kūra and Iqlīm: Sources and Seals”, Israel Numismal Journal 19 (2016), 120–132.

Cytryn-Silverman, K., and Elad, A., “Jacob Lassner, Medieval Jerusalem: History and Archaeology”, Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 53 (2022), 381–458

Daniel, R.W., “P. Petra 10 and its Arabic”, Atti del XXII Congresso Internazionale di Papirologia, Vol. 1 (Florence 2001), 331–341.

Day, Florence E.: Correspondence stored at Katholieke Universiteit Leuven and the Harvard Art Museums archive.

De Langhe, R., “Eenzaam in de woestijn van Juda”, Onze Alma Mater 8 (1954), 1–6.

Grohmann, A., Arabic Papyri from Ḫirbet El-Mird (Leuven 1963).

Haber, M., and Gutfeld, O., “Through the White Desert of the Buqeiʿa: Preliminary Results from the Inaugural Excavation Season at Ḥorbat Hyrcania”, in Peleg-Barkat, O., et al. (eds.), New Studies in the Archaeology of Jerusalem and its Region (Jerusalem 2024), 103–28.

Hoyland, R.G., “Arabic and Greek in Nessana and the Near East before and after the Muslim Conquest”, in Gajda, I. and Briquel Chatonnet, F. (eds.), Arabie-Arabies: volume offert à Christian Julien Robin (Paris 2023), 255–282.

---- “Forgotten Papyri of the Judaean Desert: The Khirbet Mird Corpus from Late Antiquity

to Early Islam”, Israel Exploration Journal 74 (2024), 102–119.

Sharon, M., “Shape of the Holy”, Studia Orientalia 107 (2009), 283–310.

Wright, G.R.H., “The Archaeological Remains at El Mird in the Wilderness of Judaea”, Biblica 42 (1961), 1–27 (with appendix by J. Milik on the literary sources).

Cite this article

Hoyland, R. 2024. “From Jerusalem to New York: the Journeyings and Insights of a Lost Arabic Papyrus, P. Mird Ar. 102.” Document of the Month. Invisible East. doi: 10.5287/ora-pdydonvvx.

About the author

Robert Hoyland is a Professor of Late Antique and Early Islamic Middle Eastern History at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, New York University.

The online series, Document of the Month, presents some of the most interesting and revealing medieval documents from the desks of Invisible East researchers and their colleagues worldwide. Each piece in the series is dedicated to a single document or a closely related group of documents from the Islamicate East and tells their story in an engaging and accessible way. You will also find images, editions and translations of the documents. If you would like to contribute to the Document of the Month series, please, get in touch with Nadia Vidro.