Document of the Month 4/25: A Judeo-Arabic Bible Commentary

A Judeo-Arabic Bible Commentary in the Bamiyan Papers:

A Family Heirloom or a Scholar's Tool?

by Nadia Vidro

Introduction

The Invisible East corpus contains manuscripts in many different languages. Most fragments are in New Persian, but others are in Judeo-Persian, Middle Persian, Bactrian, Sogdian, Arabic, Khotanese, Old Uighur, Chinese, Tibetan, and Sanskrit. Only one manuscript in the entire corpus is in Judeo-Arabic, a Jewish form of Arabic traditionally written in Hebrew characters. In this instalment of the Document of the Month series, I present this unique manuscript and ask how common knowledge of Arabic was among Persian-speaking Jews in pre-Mongol Iran and Afghanistan. I do this by juxtaposing the little we know about Jews in western Iran with their contemporary co-religionists in Bamiyan.

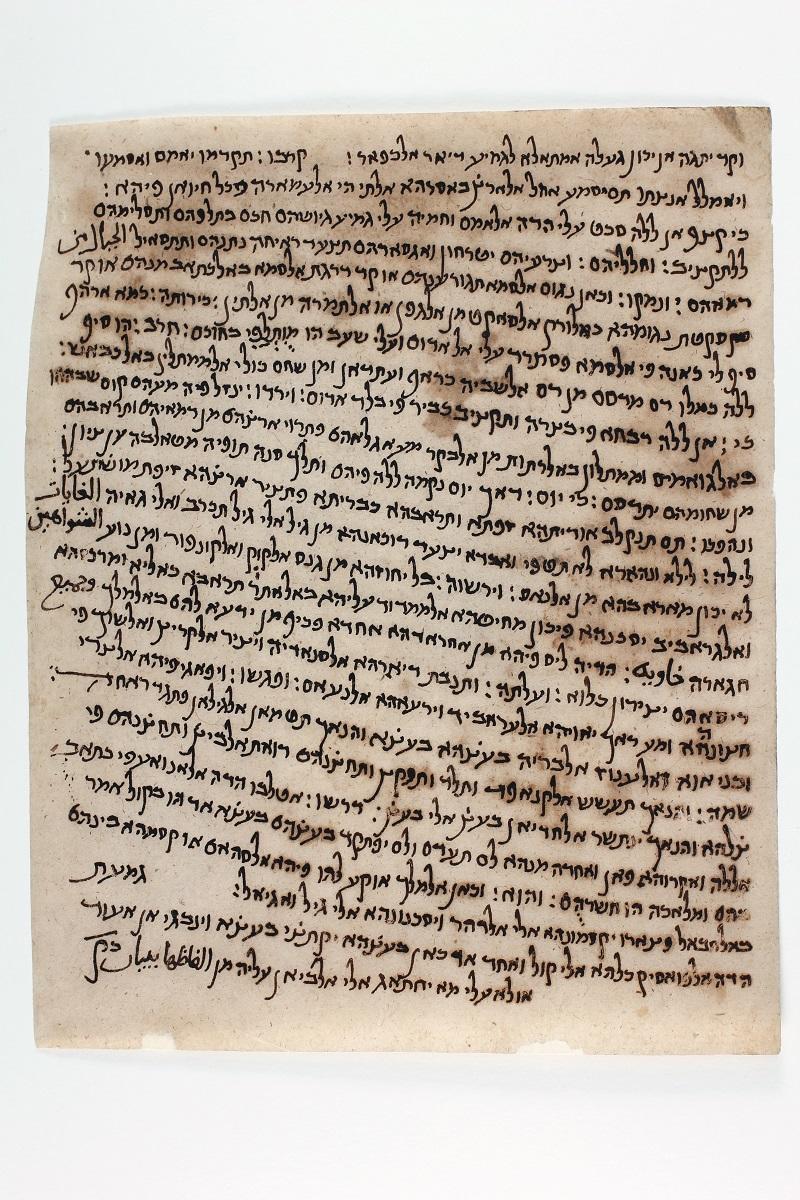

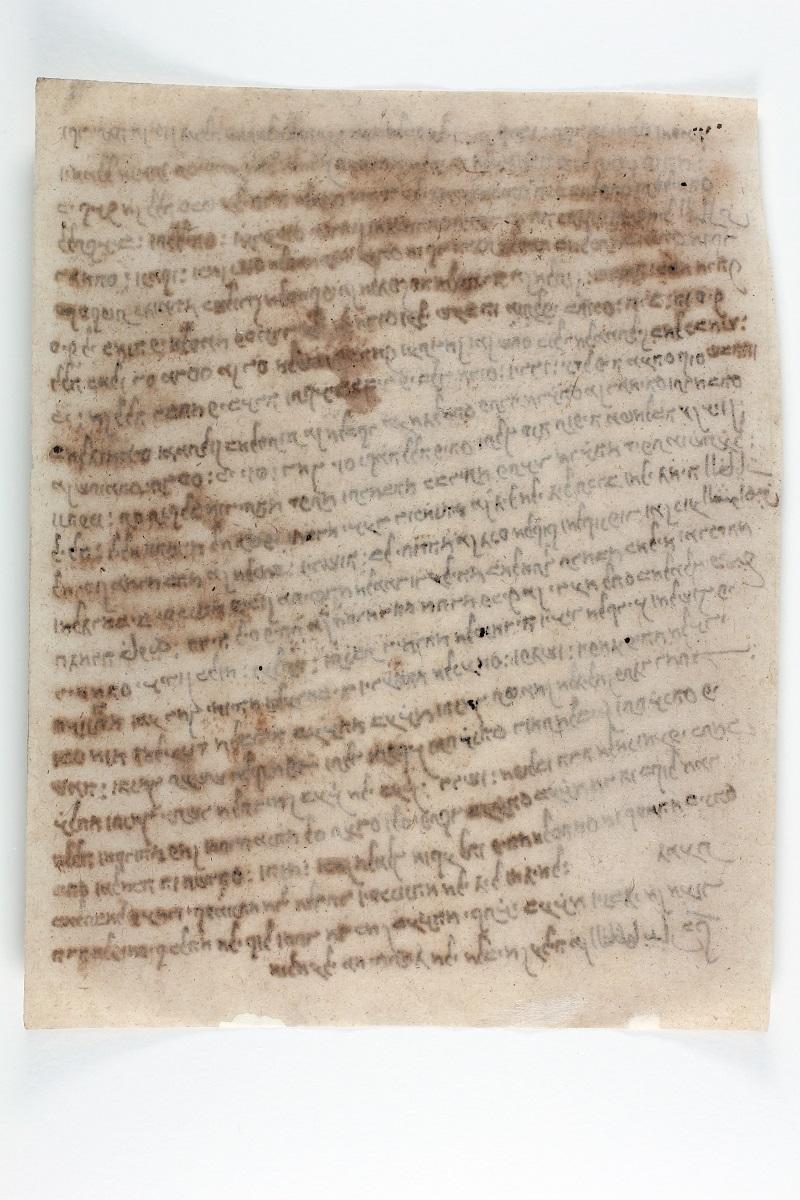

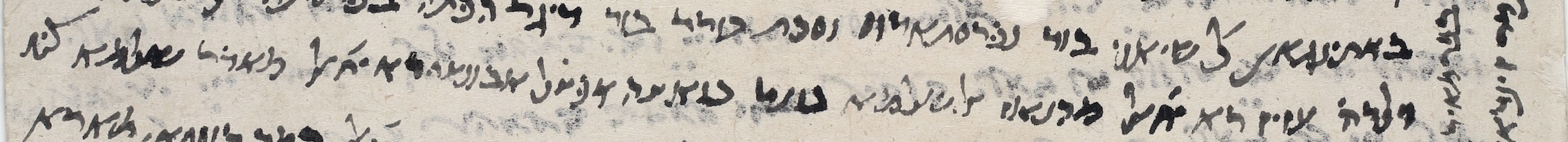

This month’s fragment is from the Bamiyan Papers (also known as the Afghan Geniza) and consists of two folios. One folio is preserved in the National Library of Israel under the classmark NLI Ms.Heb.8333.6 (Figure 1). The whereabouts of the second folio are unknown but a record of it exists in the NLI International Collection of Digitized Hebrew Manuscripts (Ktiv), and digital images can be viewed inside the library building (search by system number: 997012718874405171). The folios can be tentatively dated, on paleographic grounds, to the 11th century CE. In this article, I will focus on NLI Ms.Heb.8333.6, but most observations and conclusions equally apply to the second folio.

Fig. 1: NLI Ms.Heb.8333.6 recto (left) and verso (right). The verso side is blank because ink leaked through from the recto and made the verso unsuitable for writing. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Israel. “Ktiv” Project.

The Context: Saadya ben Yosef al-Fayyūmī’s 10th-century CE commentary on the Bible

These folios belong to a commentary on the biblical book of Isaiah by the famous Jewish scholar and community leader Saadya ben Yosef al-Fayyūmī, better known as Saadya Gaon (882–942 CE). The head of a rabbinic academy in Baghdad, a polemicist and a polymath, Saadya produced a vast body of writings that had a lasting impact on Jewish literature and culture. His works cover philosophy, liturgy, grammar, Bible translation and exegesis, religious law, and many other areas of intellectual activity. Among Saadya’s best known works are the Tafsīr, a hugely influential translation of the Bible into Judeo-Arabic, as well as a longer running commentary on the Bible. Our manuscript belongs to a copy of this longer commentary and covers Isaiah, chapters 33–35. This part of the commentary is not preserved in any of the other known copies.

Saadya Gaon’s Bible commentary is divided into textual units that have a bipartite structure. First, a group of verses is translated from Biblical Hebrew to Judeo-Arabic. Then Saadya provides philological comments on his choice of words in the translation and interprets the section’s meaning. In our case, most of NLI Ms.Heb.8333.6 is a translation of Isaiah 34, and the second folio contains Saadya’s commentary on it. Then a new textual unit begins with a translation of Isaiah 35:1–9. To get a sense of how the translation and commentary work together, let’s consider the following example. Isaiah 34 is sometimes titled “The indignation of the Lord against all nations”. This fits well with the Hebrew text, which in the King James Version opens as follows: "Come near, ye nations, to hear; and hearken, ye people: let the earth hear, and all that is therein". Compare this to Saadya’s translation where he divides the nations into two separate groups: “Approach, O nations, and hear; harken, O communities! Then all the people on earth will hear.” In the commentary, Saadya justifies his translation by explaining that the disasters in Isaiah 34 will befall only some nations and communities, whereas the rest of the people on earth will hear about them, presumably as a cautionary tale. Saadya further clarifies that the described misfortunes will befall Edom and other “enemies of the faithful”, and especially enemies of Zion, an interpretation that he supports by referring to Isaiah 34:8. They say that every translation is an interpretation, and Saadya’s is a prime example of that.

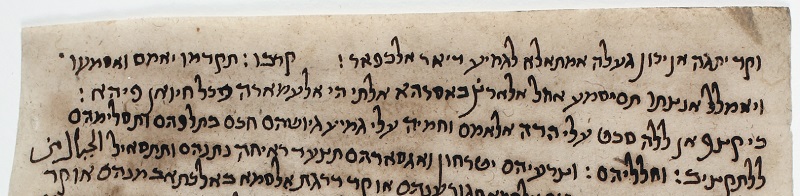

Look closely at NLI Ms.Heb.8333.6 and you will see visual clues to the commentary’s bipartite structure even if you cannot read the text. The scribe left two large empty spaces, at the top of the page and in the third line from the bottom, to separate the commentary from the translation (Figure 2). You will also see many signs that look like a colon. They separate Hebrew incipits (beginnings of biblical verses) from the Arabic translation and serve as punctuation marks in the Judeo-Arabic commentary. The use of two vertically aligned dots as punctuation marks is very common in Jewish manuscripts. It comes from the Hebrew Bible manuscript tradition, where this sign functions as a divider between verses (known in Hebrew as sof pasuq “end of a verse”).

Fig. 2: Detail of NLI Ms.Heb.8333.6 recto, showing a large empty space in the top line, punctuation marks in the form of two vertically aligned dots, and script-switching from Hebrew to Arabic in line 4. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Israel. “Ktiv” Project.

Unique aspects of this manuscript: Hebrew to Arabic script-switching

It is obvious that both Hebrew incipits and Arabic translations are written in the same script. However, Hebrew is not the only script on this page: several words are written in Arabic characters (Figures 1 and 2). Such script-switching is extremely rare in copies of Saadya’s works. In fact, this manuscript is the only example I know of! Hebrew to Arabic script-switching is common in two types of manuscripts in Judeo-Arabic. Sometimes, scribes adhered to the “one language-one script” policy. In such copies, Arabic words were written in Arabic script and Hebrew words – in Hebrew script (Figure 3).

Fig 3: Cambridge University Library, T-S Ar.31.26 recto, a treatise on Hebrew grammar. The scribe adhered to the “one language-one script” policy, writing Arabic in Arabic script and Hebrew in Hebrew script. Courtesy of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

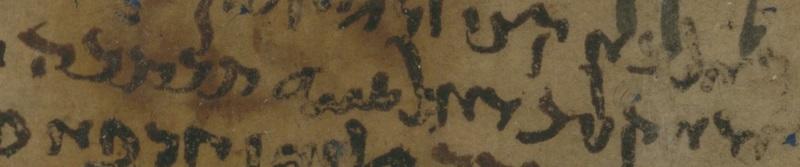

In other cases, a Jewish scribe transcoded to Hebrew script a work that was originally penned in Arabic characters. This practice was most common for astronomical, medical, grammatical and other scientific works, but is attested even for the Qur’an! This was done for the sake of convenience since most Jewish readers were more at home with Hebrew script. Such transcoding could occasionally lead to slips of the pen when a scribe got distracted and copied a word as they saw it. Additionally, if a scribe struggled to decipher a word or a phrase, they left it untransliterated and tried to copy it as best they could (Figure 4).

Fig 4: Detail of Cambridge University Library, T-S 24.31 verso. A grammar of Classical Arabic transcribed into Hebrew characters, with some words left untrasliterated by the scribe. Courtesy of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

Clearly, neither scenario applies in our case. The scribe did not adhere to the “one language-one script” policy because only a few isolated words are in Arabic script. He also could not have struggled with the decipherment of these words. Firstly, most of them are common words such as al-jibāl “the mountains”, min “from” (line 4), wa-jamīʿ “and all” (line 16). Secondly, the scribe could take clues from the biblical text. Finally, all words in Arabic script are fully dotted, showing that the scribe knew perfectly well what he was writing. In contrast, scribes who could not understand a grapheme usually did not attempt to add diacritics. If so, a different explanation must be sought. The fact that most words in Arabic characters appear at the ends of lines suggests that our scribe used Arabic script as a margin keeping device. Copyists often tried to create a relatively straight left margin, for visual effect. In Judeo-Arabic manuscripts, the most common way to do this was to write the definite article al- at the end of a line and move the rest of the word to the new line. Our scribe appears to have preferred a different method. When insufficient space remained to copy a whole word in Hebrew, he switched to the more economical Arabic script. This device is extremely rare in Judeo-Arabic literary texts but is known from some letters in the Bamiyan Papers (NLI Ms.Heb.8333.29, in Judeo-Persian, datable to the first half of the 11th century, Figure 5) and in the Cairo Geniza (e.g. T-S 24.56, in Judeo-Arabic, written in Jerusalem in the middle of the 11th century, Figure 6). Note that the Jewish scribes’ ability to move seamlessly between the two scripts demonstrates their high degree of integration into the arabographic majority culture.

Fig. 5: Detail of NLI Ms.Heb.8333.29 verso. A letter in Judeo-Persian, showing Hebrew to Arabic script-switching at the end of a line. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Israel. “Ktiv” Project.

Fig. 6: Detail of Cambridge University Library, T-S 24.56 recto. A letter in Judeo-Arabic, showing Hebrew to Arabic script-switching at the end of a line. Courtesy of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

The manuscript’s provenance and place of copying

The NLI Bamiyan Papers collection is unprovenanced. The story of the documents’ discovery in a cave in Afghanistan cannot be verified, and the details of their movement between their discovery and acquisition by the library remain incomplete. This is problematic from the heritage point of view, and it also poses difficulties for researchers studying these manuscripts. Documentary materials in the collection related to Jewish individuals have been attributed, based on their content and internal dates, to the archive of a Jewish family that lived in the Bamiyan area in the first half of the 11th century CE. It is possible that literary folios in the NLI collection belong to the same archive. The paleographic dating of NLI Ms.Heb.8333.6 to the 11th century CE supports this. However, it cannot be excluded that at least some of the literary fragments are not an organic part of the collection but became admixed while in the hands of antiquities dealers.

Assuming that NLI Ms.Heb.8333.6 was discovered alongside the rest of the Bamiyani Jews’ archive, its place of copying remains unclear. Was it produced in Persian-speaking Khurasan, as most documentary Bamiyan Papers? Or was it penned in the Arabic-speaking areas of Iraq and later brought to Bamiyan? Shaul Shaked and Ofir Haim favoured the latter view and suggested that some Bamiyani Jews originally came from Arabic-speaking regions of the Middle East.

Knowledge of Arabic among Jews in the Persianate world in the pre-Mongol period

Irrespective of where the commentary was copied, at least one of its owners in Bamiyan must have been able to read it. What information do we have about the knowledge of Arabic among Jews in Khurasan and the wider Persianate world in the pre-Mongol period? Medieval Jews in what are now Iran and Afghanistan spoke various Persian dialects and wrote in several localised varieties of New Persian using Hebrew characters. Collectively, these pre-Mongol varieties are known as Early Judeo-Persian. That Persian was their primary language is evident in the Bamiyan papers where most documents related to Jewish individuals are written in this language. In addition, Jews used Hebrew and Aramaic in the religious sphere and for some of their scholarly writings. Did Arabic have a place within their linguistic repertoire?

Shaul Shaked argued that – unlike Muslims – Iranian Jews had no apparent “religious reason” to learn Arabic. He hypothesised that if some of them knew Arabic, this may be a sign of their close relations with their Muslim neighbours and business associates or a function of their origins. The use of Arabic in business records is exemplified by the only currently available Bamiyan fragment in Arabic language and script that is explicitly linked to a Jewish person. NLI Ms.Heb.8333.23 preserves “a copy of the account of Abū Isḥāq the Jew” for 411 AH/1020–21 CE. Even if Abū Isḥāq did not produce the copy, we may reasonably assume that he understood the accounts.

Knowledge of Arabic by some Persian Jewish traders writing further west is reflected in Judeo-Persian letters from the Cairo Geniza that include whole passages in Arabic (e.g. T-S K24.16, undated, edited in Shaked 2011). These letters are in Khuzestani Judeo-Persian and were probably written by Jewish merchants from southwestern Iran (which was geographically closer to Arabic-speaking communities than Khurasan) who were able to freely alternate between Arabic and Persian. It is possible that such merchants were involved in long distance trade that connected Persian- and Arabic-speaking regions.

Another area where Persian Jews’ knowledge of Arabic comes through is in medieval textual scholarship. Judeo-Persian Bible commentaries investigated by Ofir Haim demonstrate very close parallels with similar works composed in Judeo-Arabic in Jerusalem in the 10th–early 11th centuries. General knowledge of the Jerusalemites’ interpretations could reach Iranian Jews through paraphrases in Hebrew or Judeo-Persian. However, “the astonishing resemblance” that Haim observed between certain Judeo-Persian and Judeo-Arabic Bible commentaries led him to suggest that at least some Persian-speaking Jewish scholars had direct access to Judeo-Arabic sources, which implies their knowledge of Arabic. This nuances Shaked’s argument that Iranian Jews had no “religious reason” to learn Arabic. Their scriptures were not written in Arabic, but the most advanced and influential Jewish grammatical, exegetical, and legal writings of the period were. Jewish scholars in the Persianate world who wished to keep up with contemporary developments, thus, would have directly benefitted from knowing Arabic.

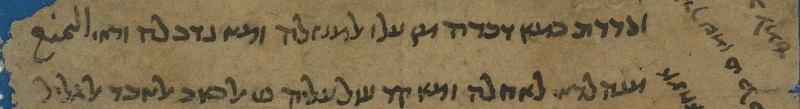

So far, we’ve seen evidence of individual Jewish merchants’ and scholars’ bilingualism in Persian and Arabic. But what about other Jewish community members? Were they bilingual, too? It is very difficult to give a general answer, but we can gain a clue from one Iranian Jewish community’s knowledge and subsequent loss of Arabic, reflected in the Cairo Genizah fragment T-S 8.237. Like NLI Ms.Heb.8333.6, T-S 8.237 belongs to an otherwise lost copy of Saadya Gaon’s Judeo-Arabic Bible commentary. This copy contained an excerpt from the commentary on the Book of Exodus, and T-S 8.237 was its opening folio. On the book’s originally blank title page, its history is recorded as follows [words in brackets are my additions, inserted for the sake of clarity].

The discourse on “This month [shall mark for you the beginning of the months]” (Exodus 12:2) [extracted] from the words of Rabbi Saadya b. Yosef al-Fayyūmī, may his soul rest in the Garden of Eden

A holy bequest to the synagogue of Urmia

This book is holy unto the Lord. It was given to me as a present by Rabbi Barukh b. Israel, the cantor in the city of Maraghah. He took it from the city of Urmia because no community remained there that knew how to read even one word of it in Arabic.

He who bequeathed it did so on the (following) condition, which he wrote upon it: “So that (people) read it and learn from it the matters pertaining to the festivals and beginnings of months as prescribed by the Sages”, etc. Since no one remains there who can read it, this condition has been nullified. However, its holiness is not nullified, for it is holy unto the Lord, His remembrance be exalted and praised.

Sela forever, amen and amen

This was written by me, Efraim b. ʿAzaryahu, the least of the scholars of Jerusalem.

(T-S 8.237 was published with an English translation in Hirschfeld 1904 and again, with a Hebrew translation, in Ratzaby 1998. My translation differs slightly from Hirschfeld’s and Ratzaby’s versions.)

Map 1: Map showing the location of Urmia, in the West Azerbaijan province of Iran, on the shores of Lake Urmia.

We learn from this note that the city of Urmia, in the West Azerbaijan province of Iran (Map 1), used to have enough speakers of Judeo-Arabic for a Bible commentary in that language to be bequeathed to their synagogue. Later, this changed and “no community remained there that knew how to read even one word of it in Arabic”. When did this occur? Since Saadya composed his commentary in the first half of the 10th century, the copy could not have been bequeathed before that. The latest plausible date for its gifting to Efraim b. ʿAzaryahu has been convincingly estimated by Haggai Ben-Shammai as the mid-12th century CE. If so, this provides an approximate chronological bracket of 950–1150 CE for Arabic knowledge among the Jews of Urmia. While it is unclear how representative Urmia was of other Jewish communities, it is noteworthy that our Bamiyan fragment NLI Ms.Heb.8333.6, tentatively datable paleographically to the 11th century CE, fits well into this date range.

Summary

This month’s document, NLI Ms.Heb.8333.6, stands out in several ways: it is the only Judaeo-Arabic fragment among the Bamiyan Papers; it preserves a portion of Saadya Gaon’s Bible commentary not found elsewhere; and it represents a rare literary fragment that employs script-switching for the aesthetic purpose of margin keeping. Assuming it is an organic part of the cache – and not an admixture from a dealer’s collection – the presence of NLI Ms.Heb.8333.6 in the Bamiyan Papers may suggest that at least some Bamiyani Jews originally came from Arabic-speaking regions of the Middle East, and their descendants may have kept the manuscript as a family heirloom. Alternatively, it may have belonged to a scholarly member of their community who had learned Arabic to engage with contemporary developments in Jewish religious thought.

Ben-Shammai, Haggai. “New and Old: Saadya’s Two Introductions to His Translation of the Pentateuch”. Tarbiz 69/2 (2000): 1999–210 [in Hebrew].

Connolly, Magdalen. The Judaeo-Arabic Letters of Daniel ben ʿAzaryah. Unpublished MA Dissertation. Cambridge, 2014.

Gindin, Thamar E. “Judao-Persian Communities viii. Judeo-Persian Language”. In Encyclopædia Iranica Online. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/judeo-persian-viii-judeo-persian-language

Haim, Ofir. “Documents from Afghanistan in the National Library of Israel”. Ginzei Qedem 10 (2014): 9–28.

–––. “An Early Judeo-Persian Letter Sent from Ghazna to Bāmiyān (Ms. Heb. 4°8333.29)”. Bulletin of the Asia Institute 26 (2016): 103–119.

–––. “What is the ‘Afghan Genizah’? A Short Guide to the Collection of the Afghan Manuscripts in the National Library of Israel, with the Edition of Two Documents”. Afghanistan 2/1 (2019): 70–90.

–––. Early Judeo-Persian Biblical Exegesis: The Manuscripts in the British Library and in the National Library of Russia. Unpublished PhD Thesis. Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2020.

Hirschfeld, Hartwig. “The Arabic Portion of the Cairo Genizah at Cambridge. (Fourth Article): Further Saadyāh Fragments”. The Jewish Quarterly Review 16, no. 2 (1904): 290–99.

Malter, Henry. Saadia Gaon: His Life and Works. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1921.

Paul, Ludwig. “Persian Language i. Early New Persian”. In Encyclopaedia Iranica Online. https://doi.org/10.1163/2330-4804_EIRO_COM_11377

Ratzaby, Yehuda. Rav Saadya’s Commentary on Exodus. Jerusalem: Mossad Harav Kook, 1998 [in Hebrew].

Shaked, Shaul. “Persian-Arabic Bilingualism in the Cairo Genizah Documents”. In From a Sacred Source: Genizah Studies in Honour of Professor Stefan C. Reif. Eds Outhwaite, B. and S. Bhayro. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 2011, 319–330.

–––. “Early Persian Documents from Khorasan”. Journal of Persianate Studies 6 (2013): 153–162.

Cite this article

Vidro, N. 2025. “A Judeo-Arabic Bible Commentary in the Bamiyan Papers: a Family Heirloom or a Scholar's Tool?” Document of the Month. Invisible East. doi: 10.5287/ora-kz8podva5.

About the author

Nadia is a cultural and intellectual historian of medieval Jews in the Middle East, with a strong focus on Qaraism. In her PhD and early post-doctoral research, she studied Qaraite treatises on Biblical Hebrew grammar, and worked on the transmission of grammatical knowledge between the Muslim and the Jewish cultures. Nadia's more recent research has been on the history of the Jewish calendar and the socio-historical implications of calendar diversity. Nadia is the Editorial Fellow in the Invisible East Programme.

The online series, Document of the Month, presents some of the most interesting and revealing medieval documents from the desks of Invisible East researchers and their colleagues worldwide. Each piece in the series is dedicated to a single document or a closely related group of documents from the Islamicate East and tells their story in an engaging and accessible way. You will also find images, editions and translations of the documents. If you would like to contribute to the Document of the Month series, please, get in touch with Nadia Vidro.