Document of the Month 6/25: “She Smells with a Fragrant Nose"

Arabic Erotic Verses from the 8th Century: A Fragment from Dhū l-Rummah’s Bāʾiyyah with Commentary

by Geert Jan van Gelder

Most of the documents of the so-called Bamiyan Papers, also known as the “Afghan Geniza”, are in Persian and the texts are not literary. The fragment that is discussed here is uncharacteristic on both counts: it is in Arabic and part of Arabic literature. Since the provenance of the collection is shrouded in uncertainties, it is not clear if the fragment was originally part of its main body.1

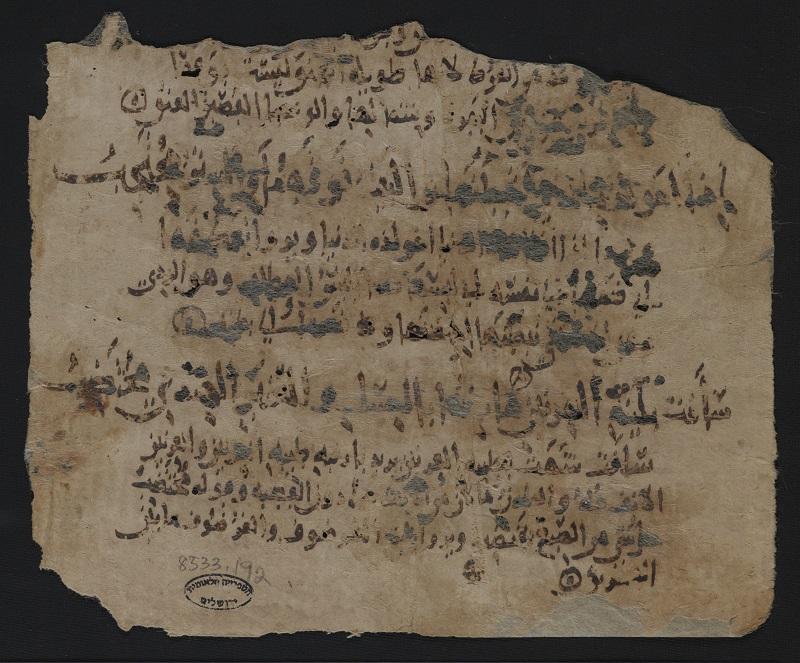

The fragment, one folio, preserved in the National Library of Israel with the incongruous classmark NLI, Ms. Heb. 8333.192 (it is not a Hebrew manuscript), contains verses of a famous Arabic qasida (long poem in monorhyme) by Dhū l-Rummah, with commentary (sharḥ) by an unknown author. The text, thirteen lines on each side, seems to be written on paper and the partly vowelled script looks old, at least to me (not a specialist in early Arabic palaeography).

Fig. 1: NLI, Ms. Heb. 8333.192, recto. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Israel. “Ktiv” Project.

The poet and his poem

Ghaylān ibn ʿUqbah, known as Dhū l-Rummah (d. 117/735-6), is one of the great poets of the Umayyad period, often called the last major Bedouin poet. Several explanations are given of his nickname, “The One with the Frayed Rope” (perhaps after a charm he wore, or because he used the word rummah “frayed rope” in a poem). The poet and critic Salma K. Jayyusi calls him “artistically the most important poet of his age and undoubtedly one of the greatest poets of the Arabic language”.2 The poem quoted on the fragment is known as “Dhū l-Rummah’s Bāʾiyyah” (“poem with rhyme consonant B”), even though he composed several other poems on this rhyme consonant. It is a long poem by the standards of his age, 126 or 131 verses (depending on the recension) in basīṭ metre, each verse having 28 syllables and rhyming in -bū. The poem is not addressed to any caliph or any other patron; it deals with love and the desert. Dhū l-Rummah must have thought highly of it himself: it is said that he kept working on it, adding verses until his death,3 which could explain its length. It opens the Diwan (his collected poetry) in the editions by C. H. H. Macartney and by ʿAbd al-Quddūs Abū Ṣāliḥ.4

The verses

The recto side of the fragment (Figure 1) contains two verses (verses 16–17, ed. Macartney, p. 4, ed. Abū Ṣāliḥ, pp. 30–31); they are the lines that stick out at the right and left margins. In addition to the commentary on these verses the fragment also contains part of the commentary on the preceding verse. Here are the two verses (recto, lines 3 and 7, Figure 2):

إذا أخو لَذَّةِ الدُّنْيا تَبَطَّنَها والبيْتُ فَوْقَهُما باللَّيْلِ محتجِبُ

سافَتْ بِطَيِّبةِ العِرْنِينِ مارِنُها بالمِسْكِ والعَنْبَرِ الهِنْديّ مختضِبُ

Idhā akhū ladhdhati l-dunyā tabaṭṭanahā | wa-l-baytu fawqahumā bi-l-layli muḥtajibū

Sāfat bi-tayyibati l-ʿirnīni mārinuhā | bi-l-miski wa-l-ʿanbari l-hindiyyi mukhtaḍibū

Fig. 2: Detail of NLI, Ms. Heb. 8333.192, recto, showing lines 3 and 7, verses 16–17. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Israel. “Ktiv” Project.

For those interested in poetic metres (there are some people who are): the metre, called al-basīṭ, can be schematically represented as XXSL XSL LLSL SSL | XXSL XSL LLSL SSL, where S stands for a short syllable, L for a long one, and X for a short or a long syllable. A short syllable ends in a short vowel (e.g. ta, bi ) and a long syllable ends either in a long vowel (hā, bū) or in a consonant (dun, mis). Since a verse may not end in a short vowel, such a vowel in the rhyme is automatically lengthened, even if not written as long in Arabic script. This is reflected in the above transcription: muḥtajibū, mukhtaḍibū.

The poem may be celebrated but I don’t know of any published complete translation into a modern western language. The lack of modern translations and studies of the poem as a whole may be due to its length, to its difficulty (Dhū l-Rummah’s poetry is a treasure trove for lexicologists), and perhaps to the absence of what many modern Arabists expect from a qasida, believing it should properly have a final section in praise of the poet’s tribe, or of a patron, perhaps combined with invective. There is a slim doctoral thesis (forty pages) on the poem by Rudolf Smend, De Dsu r-Rumma poeta arabico et carmine eius ما بال عينك منها الماء ينسكب commentatio (Bonn, 1874), which offers a short introduction, an edition, a Latin translation, and minimal annotation. The title contains the opening hemistich of the poem (mā bālu ʿaynika minhā l-māʾu yansakibū), with which the poet addresses himself: “How come your eyes are pouring out water?”. Poets very often open their poems tearfully speaking of past love. In the present poem, the poet first describes the desert dwelling where his beloved, Mayyah (frequently mentioned in his poems), once stayed. From verse 11 onward he describes her: her bright and spotless face, her figure with slender waist and well-formed backside. The two verses in our fragment are part of this section. Here is Smend’s Latin translation (p. 7), followed by mine:

16 Si frater deliciarum huius mundi ea intime utebatur et tentorium super ambos nocte velatum erat,

17 odorabatur (nasu), cuius radix fragrabat, cuius partes molles musco et ambaro Indico tinctae erant.

16 When a man familiar with this world’s delight lies belly-to-belly with her,

and the tent above the two is veiled by the night,

17 She smells with a fragrant nose, the soft tip of which

is tinged with musk and Indian ambergris.

The verb tabaṭṭana is sometimes explained as “using as biṭānah, i.e., the lining of a piece of clothing”, meaning “to lie on top of”. But deriving it directly from baṭn, “belly” is also possible, and I prefer it. The verb is already used in a poem by the famous pre-Islamic poet Imruʾ al-Qays: Ka-anniya (...) lam atabaṭṭan kāʿiban dhāta khalkhālī, “As if I (...) have never lain belly-to-belly with a firm-breasted, anklet-wearing young woman!”.5 Smend’s Latin is rather chaste, but Lane’s Lexicon, quoting medieval Arabic lexicons, is more explicit, although he too has recourse to Latin (parentheses in square brackets are mine): “He made his بَطْن [baṭn, “belly”] to be in contact with that of a girl, skin to skin (...) or inivit puellam ; i.e. أَوْلَجَ ذَكَرَهُ فِيهَا [he inserted his penis into her].”

In verse 17 one would perhaps expect the poet’s persona to do the smelling, but in the Arabic it is the woman; of course, it is in fact the poet-lover who enjoys her fragrance. It is a nosy verse, because ʿirnīn means in fact “the bridge, or upper part, of the nose” and sometimes “the whole nose", and mārin means “the soft parts”. It is therefore quoted in a chapter on noses in an anthology by the poet al-Sarī al-Raffāʾ (d. ca. 362/972).6

The Arabic commentary

Parts of the text of the commentary on these two verses (recto, lines 4–6, 8–11) are difficult to read, as a result of corrosion or general wear and tear, and I shall not give a transcription. The commentator simply glosses the more unusual words: “sāfat : she smells”; “al-ʿirnīn : the bridge of the nose, or the whole nose”, “al-mārin : the nose below the bridge”, etc. As far as I can see, it is not identical with the commentary by Abū Naṣr Aḥmad ibn Ḥātim al-Bāhilī (d. 231/846), given in Abū Ṣāliḥ’s edition of the Diwan. As Fuat Sezgin says, there are many commentaries on this qasida,7 and this very short fragment is probably either part of one such commentary or part of a commentary on the whole Diwan, on which there are also many commentaries.8

On recto, lines 1–2 a few words are readable of the commentary on the preceding verse (which is not on the fragment): al-qurṭ (“eardrops”); ṭawīlat al-ʿunuq (“long-necked”), qaṣīr al-ʿunuq (“short-necked”). These expressions cannot be connected with verse 15 in the standard editions; they belong to verse 21, which mentions Mayyah’s eardrops, alluding to her long and shapely neck. Clearly, it is another recension; and indeed in the version in the 10th-century collection Jamharat ashʿār al-ʿArab by Abū Zayd al-Qurashī9 this “neck verse” immediately precedes verses 16-17 discussed above.

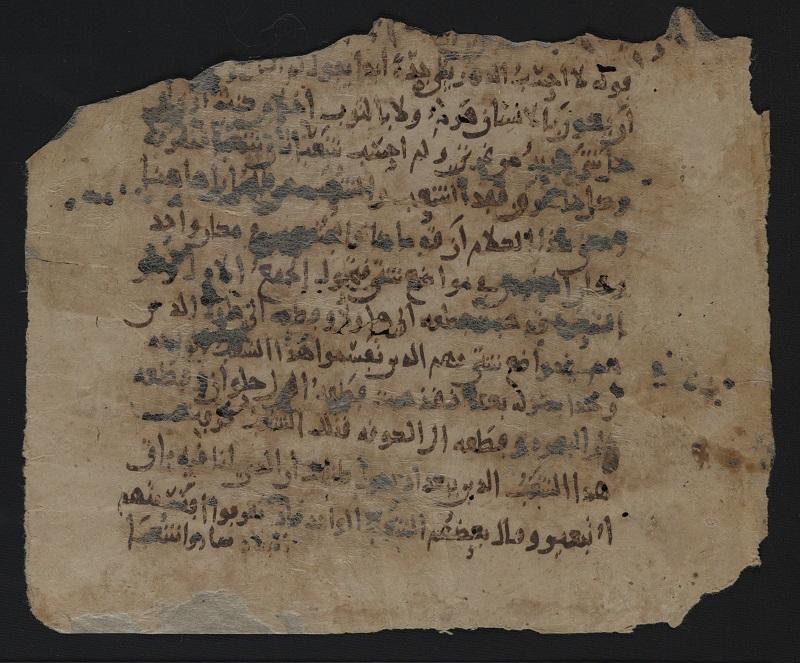

Fig. 3: NLI, Ms. Heb. 8333.192, verso. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Israel. “Ktiv” Project.

The verso side (Figure 3) contains part of the commentary on verse 24 of the Diwan as edited by Abū Ṣālih (p. 38), which is verse 29 of Macartney’s edition (p. 7). In the two preceding verses the poet thinks of the girl he fell in love with and “the nights of pleasure (layāliya l-lahwi )” he had; then he says this verse, itself not on the fragment:

لا أَحْسَبُ الدَّهْرَ يُبْلي جِدَّةً أَبَدًا ولا تَقَسَّمُ شَعْبًا واحِدًا شُعَبُ

lā aḥsabu l-dahra yublī jiddatan abadan | wa-lā taqassamu shaʿban wāḥidan shuʿabū

Smend’s translation (p. 9), followed by mine:

quum non putarem tempus unquam novitatem triturum esse, neque unam gentem divisuras esse factiones.

I had not thought that Time would ever wear out any cloth that once was new,

and that the gathered single tribe would split up in clans.

The commentary, edited below, is partly identical with that in Abū Ṣāliḥ’s edition (p. 39). Because there is much that I am unable to read in this commentary I shall not venture to translate it in full. It opens with: “With his words ‘I had not thought that Time would ever wear out any cloth that once was new’ he says: I had not thought that a human being would grow old and decrepit or that a piece of clothing would wear out; I used to believe, in my naivety (min ghirratī), that everything would stay new” (lines 1–3). All of the following is about the second hemistich, which employs the cognate words shaʿb (“large tribe, confederacy of tribes, people”) and shuʿab, explained as “(separate) tribes or clans” or “branches” (line 3). As Aḥmad ibn Ḥātim al-Bāhilī says in his commentary (given in Abū Ṣāliḥ’s edition), the poet refers to the seasonal movement of clans of a tribe which gather at the time of herbage (al-rabīʿ ) and then disperse again; a phenomenon that gave rise to the innumerable departure scenes in Bedouin-style poems, as alluded to above, with the sad poet-lover lamenting his beloved’s absence. Interestingly, the unknown commentator seems to mention the places to which such clans may go: to Ḥulwān (on the border of Iraq and Iran, at a pass in the Zagros mountains, line 9), to Basra, or to Kufa (line 10), which are not the usual Arabian locations where tribes and clans might go. Dhū l-Rummah was active in Basra and Kufa, but it is very doubtful that Ḥulwān played any part in his life; he does not mention it in his poetry. His own tribe, ʿAdī, was based in Central Arabia. As Régis Blachère writes, “There is every reason to think that during his life he remained in close contact with his tribal group in Central Arabia”.10 It looks as if the commentator also mentions Baghdad (line 11), which was founded some three decades after the poet’s death. That Dhū l-Rummah’s poetry travelled much further afield than he himself is strikingly proved by this fragment found in Afghanistan.

Arabic poetry in the Persianate world

One may wonder why this Arabic poem, or part of it at least, ended up in a country where Arabic is not a spoken everyday language. But it is not strange, because Arabic was used there as a literary language for centuries. Arabic literary anthologies from the 11th century such as the famous Yatīmat al-dahr by al-Thaʿālibī (d. 429/1039) and Dumyat al-qaṣr by al-Bākharzī (d. 467/1075) include Arabic poets from Ghazna, Balkh, or Taliqan, all in present-day Afghanistan. More than a century later, ʿImād al-Dīn al-Iṣfahānī (d. 597/1201) has sections on Arabic poets from Balkh and Ghazna in his large anthology, Kharīdat al-qaṣr.11 Poets and literati were of course familiar with the classics of former ages, such as Dhū l-Rummah’s Bāʾiyyah.

Notes

1For a survey of the collection, see Haim, “What is the ‘Afghan Geniza’?”.

2Jayyusi, “Umayyad Poetry”, 427. See on him also e.g. Sezgin, Geschichte, II, 394–397 (addendum in vol. IX, 283), and van Gelder, “Dhu al-Rummah”. Abbott, “Verses from an Ode of Dhū al-Rummah” deals with two joined folios on papyrus with verses from another poem.

3Al-Iṣfahānī, al-Aghānī, xviii, 23.

4Dhū l-Rummah, Dīwān (Macartney, 1–35, Abū Ṣāliḥ, 9–136).

5See e.g. al-Baṭalyawsī, Sharḥ al-ashʿār al-sittah al-jāhiliyyah, i, 78.

6Al-Raffāʾ, al-Muḥibb wa-l-maḥbūb wa-l-mashmūm wa-l-mashrūb (Lover, Beloved, What is Smelled, and What is Drunk), i, 209.

7Sezgin, Geschichte, ii, 397, ix, 283, listing manuscripts in Istanbul, Ankara, Cairo, Jerusalem, Bankipore, Berlin, Tehran.

8Sezgin, Geschichte, ii, 396, ix, 283, again listing numerous manuscripts.

9Al-Qurashī, Jamharat ashʿār al-ʿArab, 749. This anthology has seven sections, each section containing seven famous poems, beginning with the pre-Islamic Muʿallaqāt. Dhū l-Rummah’s poem is found in the last section, together with other Umayyad poets such as Jarīr, al-Farazdaq, and al-Akhṭal. The order of the verses, compared with the numbering of Diwan editions, is 1–6, 9, 7–8, 10, 13–14, 11–12, 19–20, 15, 18, 21, 16–17, 22 etc., showing, incidentally, that many individual verses or small groups of verses are easily lifted from their context in early Arabic poetry.

10Blachère, “Dhū ’l-Rumma”, and see also his Histoire de la littérature arabe, [iii,] 534.

11ʿImād al-Dīn al-Iṣfahānī, Kharīdat al-qaṣr, Qism fī dhikr fuḍalāʾ ahl Khurāsān wa-Harāt, 108–119, 130–158.

NLI, Ms. Heb. 8333.192=4, verso. Illegible characters are represented by series of dots. Transcription by Geert Jan van Gelder.

قوله لا أحسبُ الدهر يُبلي جدّة أبدًا يقول لم [أكن أحسب]

أن يكونَ بالإنسان هَرمٌ ولا بالثوبِ اخلاق كنت أرى [أن]

كلّ شي جديدٌ من غرتي ولم أحسب شَعبا تاتي شعبا فتفرقه

وكل هـ...... الشعب والشُعب هو قبائل هاهنا

ومعنى هذا الكلام أن قوما كانوا مجتـ[ـمعين في] مكان واحِد

وكان آ[خر زمن؟] في مواضع شتى فتحول الجمعُ الأول وهو

الشعب ...... و[قـ]ـطعة الى ... وقط[ـعة] الى ... الذين

هم بمواضع شتى فهم الذين تقسموا هذا الشعب ...

وهذا ..... بعد نفذ .... قطعة الى ... حلوان وقطعة

الى البصرة وقطعة الى الكوفة فتلك الشعوب ...

هذا الشعَبُ الذين ببغداد ... او الذي انا فيه باق

... وقال بعضهُم الشعب الواحد ... فقسمهم

... صاروا شُعبَا

Primary Sources

al-Bākharzī, Abū l-Ḥasan ʿAlī ibn al-Ḥasan. Dumyat al-qaṣr wa-ʿuṣrat ahl al-ʿaṣr, ed. Muḥammad Altūnjī, 3 vols. Beirut: Dār al-Jīl, 1993.

al-Baṭalyawsī, Abū Bakr ʿĀṣim b. Ayyūb. Sharḥ al-ashʿār al-sittah al-jāhiliyyah, ed. Nāṣīf Sulaymān ʿAwwād, 2 vols. Beirut – Berlin: Klaus Schwarz, 2008 (Bibliotheca Islamica, 47).

Dhū l-Rummah. Dīwān, ed. Carlile Henry Hayes Macartney. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1919.

Dhū l-Rummah. Dīwān, ed. ʿAbd al-Quddūs Abū Ṣāliḥ, 3 vols. Beirut: Muʾassasat al-Īmān, 1982.

ʿImād al-dīn al-Iṣfahānī. Kharīdat al-qaṣr wa-jarīdat al-ʿaṣr, Qism fī dhikr fuḍalāʾ ahl Khurāsān wa-Harāt, ed. ʿAdnān Muḥammad Ṭuʿmah. Tehran: Āyin-i Mīrāth, 1999.

al-Iṣfahānī, Abū l-Faraj. al-Aghānī, 24 vols. Cairo: Dār al-Kutub / al-Hayʾah al-Miṣriyyah al-ʿĀmmah li-l-taʾlīf wa-l-nashr, 1927–1974.

al-Qurashī, Abū Zayd Muḥammad ibn Abī l-Khaṭṭāb. Jamharat ashʿār al-ʿArab, ed. ʿAlī Muḥammad al-Bijāwī. Cairo: Nahḍat Miṣr, 1981.

al-Raffāʾ, al-Sarī ibn Aḥmad. al-Muḥibb wa-l-maḥbūb wa-l-mashmūm wa-l-mashrūb, ed. Miṣbāḥ al-Ghalāwanjī and Mājid Ḥasan al-Dhahabī, 4 vols. Damascus: Majmaʿ al-Lughah al-ʿArabiyyah bi-Dimashq, 1407/1986.

al-Thaʿālibī, Abū Manṣūr ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Muḥammad. Yatīmat al-dahr fī maḥāsin ahl al-ʿaṣr, ed. Muḥammad Muḥyī l-Dīn ʿAbd al-Ḥamīd, 4 vols. Cairo: Maktabat al-Ḥusayn al-Tijāriyyah, 1366/1947.

Secondary Sources

Abbott, Nabia. “Verses from an Ode of Dhū al-Rummah”, in her Studies in Arabic Literary Papyri, III: Language and Literature. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1972, 164–202.

Blachère, Régis. “Dhū ’l-Rumma”, Encyclopaedia of Islam, New [= Second] Edition, 12 vols. Leiden: Brill, 1960–2009, ii (1965), 245–246.

––. Histoire de la littérature arabe des origines à la fine du XVe siècle de J.-C. Paris: Adrien-Maisonneuve, 1952–1966.

Gelder, Geert Jan van. “Dhu al-Rummah (Abu al-Harith Ghaylan ibn ʿUqbah)”, in Michael Cooperson and Shawkat M. Toorawa (eds), Arabic Literary Culture, 500–925. Detroit: Thomson Gale, 2005 (Dictionary of Literary Biography, 311), 108–113.

Haim, Ofir. “What is the ‘Afghan Genizah’? A Short Guide to the Collection of the Afghan Manuscripts in the National Library of Israel, with the Edition of Two Documents”. Afghanistan 2/1 (2019), 70–90.

Jayyusi, Salma K. “Umayyad Poetry”, in A. F. L. Beeston et al. (eds), Arabic Literature to the End of the Umayyad Period. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983, 387–432.

Lane, Edward William. An Arabic-English Lexicon, 8 parts. London: Williams and Norgate, 1863–1893.

Sezgin, Fuat, Geschichte des Arabischen Schrifttums, Bd. II: Poesie bis ca. 430 H. Leiden: Brill, 1975; Bd. IX: Grammatik bis ca. 430 H. Leiden: Brill, 1984.

Smend, Rudolf. De Dsu r-Rumma poeta arabico et carmine eius ما بال عينك منها الماء ينسكب commentatio. Bonn, 1874.

Cite this article

Gelder, GJ van. 2025. “Arabic Erotic Verses from the 8th Century: a Fragment from Dhū l-Rummah’s Bāʾiyyah with Commentary.” Document of the Month. Invisible East. doi: 10.5287/ora-m81ejv4o8.

About the author

Geert Jan van Gelder was Laudian Professor of Arabic, University of Oxford, from 1998 until his retirement in 2012. Before that, he was Lecturer in Arabic, University of Groningen (the Netherlands). He has published widely on Classical Arabic Literature.

The online series, Document of the Month, presents some of the most interesting and revealing medieval documents from the desks of Invisible East researchers and their colleagues worldwide. Each piece in the series is dedicated to a single document or a closely related group of documents from the Islamicate East and tells their story in an engaging and accessible way. You will also find images, editions and translations of the documents. If you would like to contribute to the Document of the Month series, please, get in touch with Nadia Vidro.