Document of the Month 8/25: Template Funerary Inscriptions

Scribal Building Blocks and Funerary Inscriptions in 9th-Century Egypt

by Teresa Bernheimer

Introduction: Tombstones and scribal building blocks in the early Islamic Middle East

Our “document” of the month is a tombstone. It begins with the following inscription:

Bismillāh al-raḥmān al-raḥīm. Hādhā mā tashhadu bihi fulāna bint fulān al-fulānī ...

“In the name of Allah, most benevolent, ever-merciful. This is what someone, daughter of someone, the someone testifies …”

The inscription appears on a tombstone that is now in the Museum of Islamic Art in Cairo (Figures 1 and 2). “Someone, daughter of someone, the someone”? A name is squeezed in the space above these words: ʿAfīra bt. Ḥafṣ - a woman who perhaps lived and died in Fustat (Old Cairo) in the 9th century.

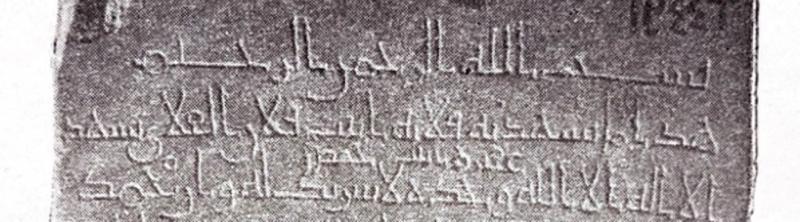

Fig. 1: Template tombstone, TEI 21124. Public domain, reproduced from Gaston Wiet, Catalogue général du Musée arabe du Caire : Stèles funéraires, t. X, Le Caire, 1942, pl. VII.

Fig. 2: Detail of TEI 21124, showing the first lines of the template tombstone, with the name “ʿAfīra bt. Ḥafṣ” squeezed between lines 2 and 3. Public domain, reproduced from Gaston Wiet, Catalogue général du Musée arabe du Caire : Stèles funéraires, t. X, Le Caire, 1942, pl. VII.

These two inscriptions – the placeholder text and the name of ʿAfīra bt. Ḥafṣ – are not evidence of a scribal error; they are evidence for a template tombstone that was eventually used, like a model car that is sold off, perhaps at a reduced price.1 It offers a rare and unusual glimpse into the compositional process behind early Islamic funerary inscriptions. As I discovered in my recent research, early Islamic tombstones are not personalized epitaphs in the modern sense, but products of patterned inscriptional practice.2 They display an “epigraphic architecture” assembled from a repertoire of pious formulae and Qurʾanic verses that could be rearranged to fit different local traditions, stone sizes, and client needs. Like a form of scribal LEGO, these inscriptions were composed from modular building blocks, often reused, sometimes unfinished, and connected to broader conventions of tradition and local practice.

This template tombstone is a smoking gun for a highly formalized industry of tombstones in the early Islamic Middle East. The Egyptian corpus is particularly rich and well documented, with thousands of tombstones surviving from the late 8th century onwards, but tombstones have survived from almost all areas of the early Islamic Middle East.3 Nearly half of the surviving examples commemorate women, a remarkable number, given their near-invisibility in Arabic literary sources. The abundance of tombstones suggests that legal discussions of the levelling of graves (taswiyat al-qubūr, the destruction of any tomb structures so that graves would not be turned into sites of worship) have likely been overstated in our perception of Islamic burial customs.4 Moreover, the thousands of extant examples make it possible to trace regional practices, workshop traditions, and the transmission of epigraphic knowledge over time. Particularly exciting has been the recent resurfacing of tombstones from Saudi Arabia: eighty-four tombstones were displayed at the 2023 Jeddah Biennale, part of an amazing art installation entitled "After Hijra” by the Saudi artist Sara al-Abdali. Since then, hundreds of images of objects previously unknown to scholarship have appeared on blogs and websites.

The Object: TEI 21124

This month’s “document” is now housed in the Museum of Islamic Art in Cairo (inventory number 13346).5 It is accessible through the Thesaurus d’Épigraphie Islamique (TEI), a large epigraphic database that makes it possible to study the inscriptional part of tombstones – usually the “front side” – in the context of thousands of other inscriptions. Our example dates to the 9th century and was first brought to scholarly attention by Gaston Wiet, who discovered it during his work on the catalogue of funerary stelae from the museum.6 What makes this object particularly striking is the use of an explicit placeholder for the name – fulāna bint fulān al-fulānī – with the visibly cramped real name inserted later, squeezed between the second and third lines. This is a template inscription for a woman’s tombstone, caught in the process of becoming an epitaph of a particular woman, ʿAfīra bt. Ḥafṣ.

The inscription is laid out in horizontal bands of text, carved in a formal angular script typical of funerary inscriptions from 9th-century Egypt. The spacing is uneven in places, especially where the real name has been added above the placeholder. Elsewhere, formulae and verse citations are spaced more generously, suggesting that the stone was carved in stages: the bulk of the text prepared in advance, with space reserved – or at least left flexible – for the individualized elements. In an example now in the State Museum of Egyptian Art in Munich (TEI 59879, Figures 3 and 4), again a tombstone for a woman, Sumayya bt. Abū Yaḥyā, we find clear evidence of this practice: at the end of the inscription, there is a blank space where part of the date should have been inscribed.7 Again, this is not a scribal error. It is part of the compositional practice of these inscriptions, which were often prefabricated and modified on demand.

Fig. 3: TEI 59879, a tombstone for Sumayya bt. Abū Yaḥyā, Staatliches Museum Ägyptischer Kunst (SMÄK), ÄS 7943. Reproduced courtesy of SMÄK.

Fig. 4: Detail of the last line of TEI 59879, reading “Year two hundred and twenty [empty space]”. Staatliches Museum Ägyptischer Kunst (SMÄK), ÄS 7943. Reproduced courtesy of SMÄK.

In terms of the inscriptional content, our “document” (TEI 21124) preserves a sequence of the most common building blocks found on Egyptian tombstones up to the 10th century. In addition to frequently cited Qurʾanic verses, the template gives a series of possible variants of the taṣliya, blessings for the Prophet Muḥammad and his family, and other pious formulae common in funerary inscriptions from this period and area.

The Building Blocks

Basmala: The inscription begins with the basmala, “In the name of Allah, most benevolent, ever-merciful”.8 This is the usual opening phrase on tombstones and most other kinds of Islamic documents. On tombstones, this formula is missing only if the top is broken off.

Shahāda: The opening formula is often followed by the shahāda, the Islamic affirmation of faith. Our tombstone is a template for the “name-encircling shahāda” pattern, meaning a compositional pattern in which a verb from the root sh–h–d “to testify” both precedes and follows the name (hādhā mā yashhadu (bihi/lahu/etc.) + name + yashhadu āllā ilāh illā allāh …, “this is what he testifies + name + he testifies that there is no god but Allah …”). Stefanie Schmidt has already remarked on this pattern and its predominance in marble tombstones.9 Indeed, this pattern is perhaps the most common for all pre-modern Islamic tombstones. As regards the inscriptional evidence for the affirmation of faith, Jere Bacharach and Sherif Anwar have noted that there were a number of variant versions in circulation in the early period of Islam. The version in TEI 21124 (Muḥammad ʿabdallāh wa-rasūluhu, “Muḥammad, the servant of Allah and His messenger”, instead of Muḥammad ʿabduhu wa-rasūluhu, “Muḥammad, His servant and messenger”) is attested as early as the caliphate of ʿAbd al-Malik (65–86/685–705).10 Among the tombstones analysed so far, this particular version is found only on examples from Fustat.

Name: Arabic names may include, besides personal names, references to ancestors, honorific titles, and further relational information such as geographic and tribal origins or professional affiliations (called the nisba, the attribution). Our placeholder makes a suggestion where the name should be placed and how it should be represented: fulāna bint fulān al-fulānī, i.e. personal name, patronymic, nisba. The added personalized version, ʿAfīra bt. Ḥafṣ, gives only the personal name (ʿAfīra) and the name of her father (Ḥafṣ). This is not uncommon, though some tombstones give much longer and more elaborate versions of the name. What the template shows, however, is that the name is to be placed between the two parts of the shahāda, making it absolutely clear who professes to the Islamic faith.

Qurʾanic verses: The shahāda leads into the first Qurʾanic verse cited on the template, Q 9:33: “He sent his messenger with guidance and the true faith in order to make it superior to the unbelievers”. The verse is slightly modified and reads arsalahu bi-l-hudā, “He sent him with guidance”, instead of huwa l-ladhī arsala rasūlahu bi-l-hudā, “He who sent His messenger with guidance”, which would be the exact Qurʾanic wording.11 There are parallels to this modification in earlier examples of Islamic coinage and inscriptions. The second Qurʾanic verse cited in lines 7 and 8 on the template tombstone is Q 22:7: “The hour of death will come without a doubt, and God will raise those who are in the graves.” Both verses are among the most commonly used on Islamic tombstones of the pre-modern period. Werner Diem and Marco Schöller, as well as Leor Halevi, have pointed out that certain Qurʾanic verses are frequently cited in funerary inscriptions in the pre-Fatimid period, with preferences changing in the course of the 10th century.12 This is indeed the case, though it must be added that beside temporal preferences, there are also local ones.

Religious formulae: Between the two Qurʾanic verses, a short religious formula is inserted, which can be termed the “ḥaqq formula” (ḥaqq meaning “true, real” or “truth, reality”).13 It affirms some of the main eschatological concepts of early Islam: the reality of paradise and hell, and the reality of death and resurrection. The ḥaqq formula has a short version (as in this template) or longer ones, and is very common in funerary inscriptions.

After the citation of Q 22:7, there are more religious formulae, beginning with various versions of the taṣliya, blessings for the Prophet and his family. This starts on line 8: “O Allah, bless Muḥammad and the family of Muḥammad/// have mercy on Muḥammad and the family of Muḥammad/// and bless Muḥammad and the family of Muḥammad as You blessed and had mercy and blessed Abraham and the family of Abraham. You are indeed praiseworthy and glorious ///.” The text make sense as it is, but I have not found another example that lists all these variants together, suggesting that these are separate elements that could be chosen from. Usually only a single taṣliya element is included in an inscription, and its choice is again dependent on locale.14

There are two more formulae after the taṣliya: “O Allah, she is Your female servant (amatuka), the daughter of Your female servant” (lines 12 and 13) and then a formula that was not very popular, as far as I have seen: “she is now in your hands” (literally, “her forelocks are in your hands”; line 13). The inscription ends with a closing formula, which is frequently found, though again with local variations: “So forgive her and overlook her faults, and illuminate her grave and make it a garden for her.” In tombstones that are attributed to Fustat, the date would be added at the very end, but this is missing here. It should be noted that the date is not an integral part of funerary inscriptions – Arabian funerary inscriptions only rarely carry a date; tombstones from Aswan usually place the date in the middle of the inscription, if it is included.

Through the modular building blocks, such as those found on this template, any tombstone can be schematically represented. Some elements have a clear position in an inscription, others could be rearranged and recombined, often with striking local specificity. The analysis of variations enables us to trace not only epigraphic preferences but also the reuse of textual and visual conventions within and across regional communities; it invites further comparison with constructions of epigraphic architecture in other materials and contexts, such as numismatics, architecture, manuscripts, documents, and other religious traditions. Indeed, the “scribal LEGO” is not unique to stone – textual reuse, flexible recombination, and a strong sense of patterned composition are found in many written artefacts.

Final Reflections: Seeing the Written Dead

What this tombstone offers is a view both into the production of an epitaph, and into the epistemology of funerary inscriptions – how people learned to write on stone, what text should be written, and how these practices were transmitted over time. It also reminds us of what is at stake in the preservation of cultural heritage in the present. Hundreds – perhaps thousands – of Islamic tombstones remain unpublished or undocumented, and many are under immediate threat of decay or loss. Recent initiatives are beginning to address this issue. These include the expanding digital archive of the Thesaurus d’Épigraphie Islamique and a large project led by the Institut français d’archéologie orientale and the Ain Shams University in Cairo, to document tombstones in the store rooms of the Museum of Islamic Art, as well as in situ at the Cairo al-Qarāfa cemeteries. These projects not only preserve inscriptions that are often at risk of literal erasure, but also make it possible to study them in context – textually, regionally, and materially. One desideratum is that specimens be photographed from all sides – not just the “front” of the inscription, but also the back and the sides, which often contain fascinating information, such as traces of reuse. As more stones are digitized and made accessible, we are slowly beginning to reconstruct the social and material contexts that shaped their production.

One important aspect of this reconstruction is the analysis of the material: as a number of scholars have pointed out, there is a difference in the material used for tombstones in different parts of Egypt (and elsewhere in the Middle East, of course) – sandstone predominantly in Aswan, and marble in Fustat.15 Many tombstones were likely not cut anew in a quarry; ancient structures were reused and material recut for tombstones, thus prescribing the material and epigraphic possibilities.

In sum, this “document” of the month touches on several questions at the heart of the Invisible East project: how texts were produced and transmitted across regions; how local traditions shaped written artefacts; and how forms of scribal and epigraphic knowledge circulated outside elite literary frameworks. Tombstones are particularly revealing in this respect: they offer access to otherwise unrecorded individuals – women, slaves, and other non-elites who are invisible in the textual record16 – and they document systems of composition that were deeply connected to regional material practices.

To conclude, I want to highlight an exceptional tombstone, one of the very few individualized epitaphs that have survived (TEI 4508, Figure 5), quite distinct from our template tombstone. It is the tombstone for a young boy who drowned, with a moving example of a very personal commemorative inscription:17

1. In the name of Allah, most benevolent, ever-merciful! Praise be to God, contentment with God’s decree,

2. faith in his power and submission to His command. This is

3. the garden (rawḍa) of the lovely, beautiful, and comely child Abū ʿUmar b.

4. Isḥāq b. Ibrāhīm b. Ayyūb al-Khawlānī, the drowned,

5. the blissful martyr. His Lord gave him to his parents as a boy, and

6. He took him (back) from them immaculate and pure without having committed

7. crime or sin when his Lord drowned him. He testified that

8. there is no God except God alone, without associate,

9. and that Muḥammad is His servant, messenger and prophet, may God’s blessings be

10. upon him since his Master has more claim to him than his parents.

11. His parents debit him to God’s account and say about

12. the affliction with regards to him, we belong to God and to Him we shall return.

13. Even if you died small, the grief is not small. You were my fragrant plant,

14. and now you are the fragrant plant of the graves. What beautiful branches

15. it has which beautifully irradiate! It was planted in the gardens of moist earth by

16. fate. He died in Shawwal of the year two hundred and fifty-nine.

Fig. 5: Tombstone for a young boy, TEI 4508. Public domain, reproduced from Hassan Hawary et Hussein Rached, Catalogue général du Musée arabe du Caire : Stèles funéraires, t. III, Le Caire, 1939, pl. XXXIX.

This moving inscription includes some elements from the inscriptional LEGO box, such as the basmala, but its content is unusual and even unique. The only Qurʾanic citation is Q 2:156, “To Allah we belong and to Allah we return”, which is attested in letters of condolence and letters connected with death, but is highly uncommon on tombstones.18 A unique element is the poem added at the end – it has parallels in literary texts, but not on a tombstone. Such links between different media and materials are fascinating, and perhaps a topic for another “document of the month”.

Notes

1 Many thanks to Christian Sahner who suggested this analogy!

2 Bernheimer/Korn 2025; Bernheimer 2025.

3 See, for instance, Hawary et al. 1932–1942; ʿAbd al-Tawab/Ory 1977–1986. Part of the collection in the Islamic Museum in Cairo was published in the ten volumes of the Catalogue général du Musée arabe du Caire, Hawary et al. 1932–1942.

4 Leisten 1990; Bernheimer 2013.

5 Hawary et al. 1932–1942, vol. X, p. 188, no. 3974; pl. VII.

6 Wiet 1952. On the contribution of Wiet to the formation of the museum in Cairo, see his obituary, Rosen-Ayalon 1972.

7 Bernheimer 2025.

8 The translation of Qurʾanic verses follows Ali 1984.

9 Schmidt 2021, pp. 356–358.

10 Examples include inscriptions on the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, on the milestones of this caliph’s road building projects, and on his coinage. See Bacharach/Anwar 2012.

11 See Bacharach 2010.

12 Diem/Schöller 2004; Halevi 2004.

13 This terminology is suggested in Bernheimer/Korn 2025, p. 84.

14 I first explored this in the context of a lecture given on 27 June 2025, “Carved in Stone: Shīʿī Funerary inscriptions and Religious Identity in Early Islamic Egypt”, in the lecture series Material Culture, Art, and Architecture of Pre-Safavid Shīʿism, organized by Ayla Santi (University of Leiden).

15 Wiet 1952; Bauden 2004; Schmidt 2021; Porter 2023.

16 See Bruning 2023 on tombstones for slaves; and Bauden 2010 for an overview of tombstones as sources for social history.

17 Edited in Diem/Schöller, vol. I, pp. 229–236. A translation of this inscription was first published in Diem/Schöller 2004, vol. I, p. 231. This translation is my own revised version.

18 Younes 2017.

TEI 21124, the Museum of Islamic Art, Cairo, n° 13346

Transcription by Teresa Bernheimer. First published by Gaston Wiet, Catalogue général du Musée arabe du Caire : Stèles funéraires, t. X, Le Caire, 1942, p. 188, n° 3974

1. بسم الله الرحمن الرحیم

2. هذا ما تشهد به فلانة إبنت فلان الفلانى تشهد

2״. عفيرة إبنت حفص

3. الا اله الا الله وحده لا شریك له وان محمد

4. عبد الله ورسوله ارسله بالهدی ودين الحق

5. لیظهره على الدين كله ولو كره المشركو

6. ن و تشهد ان الموت حق والبعث حق و ا

7. ن الساعة اتية لاریب فیها وان الله باعث من

8. فی القبور اللهم صلى على محمد و على آل

9. محمد و ارحم محمد و آل محمد و بارك

10. على محمد و على آل محمد كما صليت و رحمت

11. و باركت على إبرهيم و على آل ابرهيم

12. انك حميد مجيد اللهم انها امتك

31. ابنت امتك ناصيتها بيديك فا

14. غفرلها و تجاوز عنها و نوّر عليها

15. قبرها و اجعله عليها روضة

ʿAbd al-Tawab, ʿAbd ar-Raḥman M., and Solange Ory (1977–1986), Stèles islamiques de la nécropole d’Assouan, Textes arabes et études islamiques 7, 3 vols, Cairo.

Ali, Ahmed (trans.) (1984), Al-Qurʾān: A Contemporary Translation, Princeton.

Bacharach, Jere L. (2010), “Signs of Sovereignty: The Shahāda, Qurʾanic Verses, and the Coinage of ʿAbd al-Malik”, Muqarnas 27, 1–30.

Bacharach, Jere L., and Sherif Anwar (2012), “Early Versions of the Shahāda: A Tombstone from Aswan of 71 A.H., the Dome of the Rock, and Contemporary Coinage”, Der Islam 89, 60–69.

Bauden, Frédéric (2004), “Les stèles arabes du Musée du Cinquantenaire (Bruxelles)”, in: Frédéric Bauden, ed., Ultra mare: Mélanges de langue arabe et d’islamologie offerts à Aubert Martin, Paris/Leuven/Dudley, 175–193.

Bauden, Frédéric (2010), “Tombstone Inscriptions and Their Potential as Textual Sources for Social History”, paper presented at “Aswan Tombstones” workshop, organized by the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut in Aswan, Egypt, 13–15 February 2010.

Bernheimer, Teresa (2013), “Shared Sanctity: Some Notes on Ahl al-Bayt Shrines in the Early Ṭālibid Genealogies”, Studia Islamica 108, 1–15.

Bernheimer, Teresa (2025), “Zwei Grabsteine aus der früh-islamischen Ägypten im SMÄK: ÄS 7943 und ÄS 7944”, MAAT: Nachrichten aus dem Staatlichen Museum Ägyptischer Kunst München 34, 2–13.

Bernheimer, Teresa, and Lorenz Korn (2025), “Eleven Islamic Tombstones from Egypt: A Window into the Histories of Early Islamisation and of Modern Dislocation”, Der Islam 102, no. 1, 67–129.

Bruning, Jelle (2023), “Islamic Tombstones for Slaves from Abbasid-Era Egypt”, Slavery & Abolition 44, 616–637.

Diem, Werner, and Marco Schöller (2004), The Living and the Dead in Islam: Studies in Arabic Epitaphs, 3 vols, Wiesbaden.

Halevi, Leor (2004), “The Paradox of Islamization: Tombstone Inscriptions, Qurʾānic Recitations, and the Problem of Religious Change”, History of Religions 44, 120–152.

Hawary, Hassa, Hussein Rached, and Gaston Wiet (1932–1942), Catalogue général du Musée arabe du Caire: Stèles funéraires, 10 vols, Cairo.

Kalus, Ludvik, Frédéric Bauden, and Frédérique Soudan (2020–), Thesaurus d’épigraphie islamique, Geneva, https://www.epigraphie-islamique.uliege.be.

Leisten, Thomas (1990), “Between Orthodoxy and Exegesis: Some Aspects of Attitudes in the Sharīʿa toward Funerary Architecture”, Muqarnas 7, 12–22.

Porter, Venetia (2023), “Tombstones from Aswan in the British Museum”, in: Bernard O’Kane, Andrew C. S. Peacock, and Mark Muehlhaeusler, eds., Inscriptions of the Medieval Islamic World, Edinburgh, 241–263.

Rosen-Ayalon, Maryam (1972), “Gaston Wiet, 1887–1971”, Kunst Des Orients 8, no. 1/2, 155–159.

Schmidt, Stefanie (2021), “The Problem of the Origin of Tombstones from Aswan in the Museum of Islamic Art in Cairo”, Chronique d’Égypte 96, 353–370.

Wiet, Gaston (1952), “Stèles coufiques d’Égypte et du Soudan”, Journal asiatique 240, 273–297.

Younes, Khaled (2017), “Arabic Letters of Condolence on Papyrus”, New Frontiers of Arabic Papyrology, Leiden, 67–100.

This material was first presented as part of my paper “Inscribing Epitaphs in 8th- to 9th-Century Egypt: Templates and Typologies” at the 2025 International Medieval Congress in Leeds (Session 62: Learning and Doing Scribal and Epigraphic Work in the Islamicate World: A Comparative Approach). Many thanks to Arezou Azad, who organized this panel.

Cite this article

Bernheimer, T. 2025. “Scribal Building Blocks and Funerary Inscriptions in 9th-Century Egypt.” Document of the Month. Invisible East. doi: 10.5287/ora-yr45xgejm.

About the author

Teresa Bernheimer is a historian of the Middle East in the period 600 to 1200 CE. She is currently PI of the project Beyond Conflict and Coexistence: An Entangled History of Jewish-Arab Relations (funded by the BMFTR, Germany). Based in the Judaic Studies unit at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Munich, she leads an international team of six postdoctoral researchers across Munich, Halle, and Heidelberg.

The online series, Document of the Month, presents some of the most interesting and revealing medieval documents from the desks of Invisible East researchers and their colleagues worldwide. Each piece in the series is dedicated to a single document or a closely related group of documents from the Islamicate East and tells their story in an engaging and accessible way. You will also find images, editions and translations of the documents. If you would like to contribute to the Document of the Month series, please, get in touch with Nadia Vidro.