From University to School Classroom

From University to School Classroom:

Learning with children about the “Invisible East,” and sharing the (his)stories that documents can tell us

Zaiba Patel, 24 May 2022

On 17 May 2022, I had the pleasure of launching the first of a series of taster sessions run at UK secondary schools, aimed at sharing the results of the Invisible East (IE) research programme. In this first session, I was accompanied by the Invisible East’s Director, Arezou Azad, and post-doctoral researcher Zhan Zhang. We met a group of 19 Year 9 pupils at the Rumble Museum in Cheney School in Oxford. As this switched-on group of students reminded us, there is nothing quite like the buzz of a classroom to illuminate the importance, excitement, and joy of studying history and documents! My job as the IE Education Advisor is to make the delivery of the taster sessions for year 9 students (13-14 year olds, Key Stage 3) exciting, inspiring and historically rigorous. I developed–with input from from the IE Team–an interactive session. We had three specific aims for our session which would last 90 minutes, namely to:

- diversify and enrich students’ knowledge of the histories of the medieval Islamicate East (what lies at the heart of the IE programme)

- connect students with historians and the ways they may work

- invite students to participate in the discipline of history from an ‘Invisible East’ perspective, working with primary sources and mock-curating a related exhibition

1. Diversifying and enriching students’ knowledge of the ‘Invisible East’

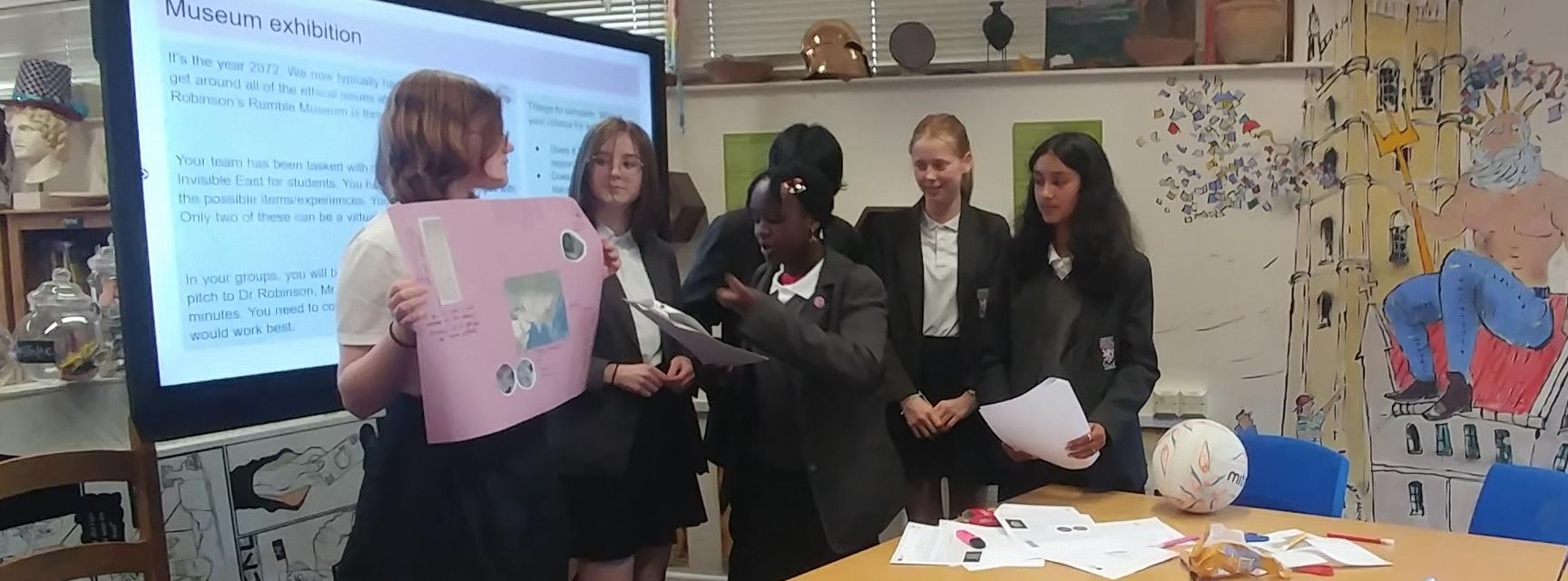

Owing to the relative "invisible-ness" of the Iranian, Afghan and Central Asian Islamicate region, as exemplified by its absence on the UK National Curriculum, it was incumbent upon us to illuminate its rich and varied history to the pupils. As a first exercise, students coloured in Iran, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, southern Kazakhstan, Pakistan, Northern India and Western China, which were labelled on a map to get a sense of space, location and topography. I then started the discussion by drawing out students’ prior knowledge of the region. Some were able to identify languages spoken and religions practised. The general consensus amongst the pupils was that Islam was the dominant religion there today, and that the region was marred by conflict and poverty, particularly in Afghanistan. Some pupils also acknowledged that there were many places, mainly the ‘-stans’, that they did know much about at all.

Image 1 caption (below): Introductory slide with the first lesson activity

Throughout the session, we unpacked the monolithic image of the region, and gained an appreciation of its diversity, and relative neglect in school curricula and university programmes as well.

As a second exercise, I introduced pupils to the earliest known text of original Persian writing; a rhymed poem written in 11th-century Bamiyan, Afghanistan. The poet (probably Muslim) had written a panegyric in praise of his patron, a Jewish landholder. Four folios later, he revealed the letter’s true purpose: the letter-writer had hosted an over-indulgent party and, as the party was winding down around him, found he desperately needed cash from the patron. The teachers were as excited as the students about what this poem taught them, and one teacher, Mr Gimson, commented that it was “both fascinating and amusing” that such an extraordinarily human letter held the title of the earliest original Persian text !

Image 2 caption (below): Students work together to decipher the primary source

Pupils fed back to the group that unpacking the poem had shown them some unexpected things about interfaith connections and wealth in the area at the time, and had given them insight into daily life. This one primary source had offered them rich revelations about the region, and enabled them to unpack preconceptions of religious and cultural homogeneity.

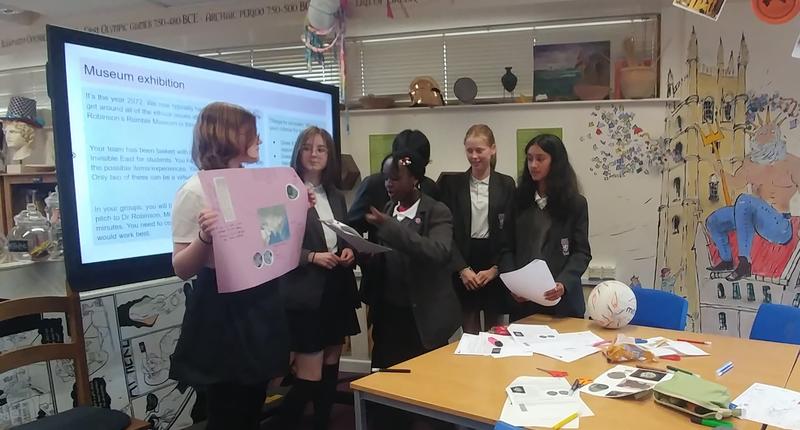

In the second half of the session, and in a third exercise, the students travelled to the year 2072, an era when Virtual Reality would be commonplace in museums. I asked them to curate an exhibition on the Invisible East for these third millennium students. The pupils worked in groups, armed with a catalogue of 12 items I had provided to them that covered a range of themes, including multiculturalism, literacy, and ordinary, everyday life. The images included photos of the Mogao Caves in western China, the Bamiyan Buddhas, and a dowry receipt from a 12th-century Persian document from Afghanistan. Pupils worked in groups of 4 or 5, with sugar paper, a pair of scissors, a glue stick and a packet of felt-tip pens. In 15 minutes, the groups produced four completely different and original presentations highlighting 2 or 3 items they had chosen as their exhibition focus, and explaining their representativeness of the selection criteria. We were impressed by the incredible insights the pupils gained in just 15 minutes; highlighting the evidence of travel and migration, religious diversity, wealth in natural resources (e.g. silver of silver plates, jade, literacy, survival of Buddhas throughout Islamic rule, etc.) and explaining how this activity had challenged an array of preconceived notions they had held.

2. Connecting with Historians

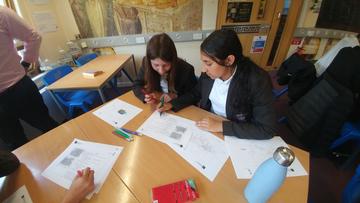

Image 3 caption (below): Dr Azad works with a group to plan their exhibition

It was evident that the engagement of the pupils with academics on the team had an inspiring and esteem-building effect on the pupils. The coverage of “non-white” topics with a diverse set of teacher-academics also reminded me of a Teaching History article, in which History teacher, Sophia Nzeribe Nascimento found that her students often had stereotypical assumptions about the professionalism of non-white and/or non-male historians. We have a way to go before the teaching body is diverse: the 2018 Royal Historical Society’s Race, Ethnicity & Equality Report found that just 4% of university historians identified as the UK category of BME (“Black and Minority Ethnic”). Introducing the class to Drs Azad and Zhan Zhang, and illuminating their brilliant work, offered a counter-image. It is important to have a diverse representation of academics to confirm to all students that university-level study of history and related subjects is a space that all students can inhabit.

3. Participating in history

Image 4 caption (below): Students present their museum exhibition

For me, offering students entry into the discipline, and valuing their voices when they do so, is an essential condition for learning to occur. As van Boxtel and van Drie’s 2017 work posits, learning is ‘entering a community of practice’ and ‘learning the language’ of the discipline.

For this reason, I also integrated into the session a fourth (and final) exercise in which students had the chance to discuss the actual research management process, including the conception phase and ethics around working with unprovenanced material. At each stage, pupils were asked how they would approach these processes in research before Dr Azad revealed what she actually did. This way, students engaged in ethics, team management, deciphering content and considering authorial intent, and extrapolating and drawing their own conclusions on what the primary sources could and could not reveal.

The final activity, in which pupils curated their exhibition, was pupil-led, giving them the opportunity to ascribe historical significance to objects as they saw fit.

Some of the teachers’ comments:

‘This was a brilliant session, with very well-thought-out activities which supported the students' thinking and learning. It was great for them to engage with primary sources, and to put themselves in the role of researchers and museum curators. This was a really engaging approach and they really enjoyed taking part - thank you!’

(Dr Robinson)

The poem was so human and so funny, and all the varied artefacts are so interesting. I think the students responded very well because the material was so stimulating and so carefully planned.

(Mr Gimson)

Image caption 5 (below): Students discussing their exhibition with Dr Zhan Zhang

To conclude, this session has made it very clear to me that there is a thirst for this kind of knowledge in schools. The pupils at Cheney School exhibited an energy and level of engagement that was impressive, not least because our event ran after pupils had spent a full day in lessons. We hope they might have found some inspiration and may even pursue history as a field of academic study in future! With special thanks to Mr Gimson, Dr Robinson and the students at Cheney School.

Bibliography

Nzeribe Nascimento, S. (2018). ‘Identity in history: why it matters and must be addressed!’ Teaching History 173, Opening Doors Edition, pp. 8-19.

Royal Historical Society, 2018. Race, Ethnicity & Equality In UK History: A Report And Resource For Change. [online] Available at: <https://files.royalhistsoc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/17205337/RHS_r... [Accessed 23 May 2022].

van Boxtel, C. and van Drie, J. (2017). Engaging Students in Historical Reasoning: The Need for Dialogic History Education. In: Palgrave Handbook of Research in Historical Culture and Education. Palgrave, pp.573–589.

About the author

Zaiba Patel is a former history teacher and education advisor to the Invisible East team. She holds a Master's degree in Learning and Teaching at the University of Oxford, where she explored decolonisation, race and the history curriculum. She is soon to begin a DPhil investigating the role of engaged pedagogies in supporting decolonisation and strengthening young people's sense of belonging in the history curriculum.