The Long Road to Kabul: Reflections on the Making of the Archaeological Gazetteer of Afghanistan

The Long Road to Kabul: Reflections on the Making of the Archaeological Gazetteer of Afghanistan

By Warwick Ball, August 2024

Almost to my surprise, the Archaeological Gazetteer of Afghanistan (AGA) has become an important reference work. I first became aware of this at a workshop in Oxford in 2012 when participants referred to sites by gazetteer site numbers rather than by name.1 This was reinforced at a seminar in London in 2016 when a number of the emerging scholars present mentioned how much they used the gazetteer when embarking on their doctoral dissertations.2 Two more recent and more ambitious mapping initiatives, the Afghan Heritage Mapping Partnership (AHMP) at the University of Chicago and the Archaeological Gazetteer of Iran at the University of California Los Angeles have acknowledged their debt to the AGA.3 In more than forty years since the AGA’s first edition in 1982, therefore, it is worth reflecting on its modest origins, and perhaps to learn from its lessons leading to its present incarnation in a 2nd edition.

Humble beginnings in the 1970s: card index

The AGA’s background lies, first, in the heady days of archaeological fieldwork in Afghanistan in the early 1970s, and the establishment of the British Institute of Afghan Studies (BIAS) later that decade (Fig. 1). It was probably the most exciting decade of archaeological activity in Afghanistan with French, German, Italian, Soviet, Japanese and US missions and Afghan archaeologists making groundbreaking discoveries. The British arrived on the scene as relative latecomers. Once I was installed at BIAS, I began compiling a simple card-index file of archaeological sites in Afghanistan. The card index was designed as a quick, working reference guide to the activities and publications on major archaeological sites in Afghanistan. Its aim was to serve as a tool for researchers who were coming through the institute in Kabul, and I modelled my card index after the indexes I had seen at the British School of Archaeology in Athens and the Institute of Archaeology at the University of London.

Fig.1: The British Institute of Afghan Studies, Kabul, photo taken by WB in 1981

The value of the Afghanistan sites card index grew, and it was decided to expand it into a full catalogue that encompassed as many of the known and published sites and monuments as possible. Its loose, unbound form made it easy for users of the index to constantly enlarge and update it.

Abrupt change from 1979

Nobody in the archaeological community foresaw that their fieldwork was about to end very abruptly. As late as in early 1979, digs continued as normal. My card index had now expanded into a pretty comprehensive catalogue, and it was suggested that I turn it into a book for publication. At the same time, Jean-Claude Gardin and Bertille Lyonnet, both archaeologists (and experts of ceramics) at the Délégation archaéologique française en Afghanistan (DAFA), had just completed their eastern Bactria survey. They suggested that data on miscellaneous sites and pottery collections stored and archived at the DAFA compound in Kabul, as well as data on their own survey sites, be included in my compendium

With the inclusion of this new material, the project became more ambitious and developed a two-fold aim:

- to serve as a channel for combining existing knowledge of sites in a simple, easily referable form; and

- to pool informational resources for researchers, combining new with existing material, to develop as complete and up-to-date an archaeological picture of Afghanistan as possible.

My model for this was no longer a simple card index, but the record of sites and monuments held by the Royal Commissions of Ancient and Historic Monuments of England and Scotland. In this sprit, the original Archaeological Gazetteer of Afghanistan was conceived.

Challenges: site naming, identification, and georeferencing

Turning the index into a book presented me with three key challenges, which I’ll spell out here.

1 - How do you name a site?

By its name, of course, but in a country with three major languages and many minor ones, this wasn’t so straightforward. One site with a Pashtu name like Shindand, for example, was known to Persian-speakers as Sabzavar. A site in Takhar was recorded by different investigators as Pasha Khana, Rustam Tepe, Qishlaq or ‘Dorahi – all referring to the same site.4 Which one should I chose?

Moreover, the many nationalities represented amongst the archaeological community meant that different transcriptions were used for one and the same site. For example, a site recorded by Japanese archaeologists as Char was identified on a map as Chal - Japanese having no sign for ‘L’.5 Or, a site recorded by an American investigator as Bajgina was later recorded by a Lithuanian archaeologist as Wajguna.6 The Russian pronounciation of the ‘h’ sound was ‘kh’ which lead to transcriptions of parts of names as shakhr (Persian for “city”) by Russian-speakers, but shahr by Persian-speakers. I overcame the plurality of naming options by ensuring extensive cross-referencing of place names throughout the gazetteer.

2 - What constitutes a site?

Again, this wasn’t so obvious. In most cases each entry refers to just one site, although sometimes I had to lump them together. For example, Safid Dagh and Surkh Dagh are included under the site name of Nad-i ‘Ali.7 Equally, many of the Hadda stupa-monastery sites are grouped under one entry.8 And Dashli sites scattered across the Balkh plain are grouped into just four entries, according to particular concentrations or unique characteristics.9

Where surveys had been particularly intensive, I grouped sites logically together to avoid regional imbalances. This applied, for example, to the Gardin-Lyonnet East Bactria surveys and the Marc Le Berre’s work at DAFA on the Bamiyan fortifications, where specific lines of towers formed a single complex. Thus, the concentration of, say, Achaemenid sites in eastern Bactria should not be read as meaning that there were more Achaemenid settlements there than elsewhere in Afghanistan; It simply means that the area has been more intensively surveyed than others.

Decisions were not easy! Once again, cross-referencing overcomes some of these difficulties, and regional maps help in clarifying locations. I included in the regional maps all features of potential archaeological interest recorded on my base maps: ruins, fortifications, caves, graves, etc.

3 - Where are sites located?

Locating certain sites proved difficult, especially when they were described in 19th-century sources which were vague on directions and place names (actually, many a 20th-century investigator could be equally vague in their descriptions!) I had access both to the 1:100,000 stereotopographic maps of 1960 and 1968, prepared by the United States and Soviet Union for the Ministry of Mines of Afghanistan, as well as the old Survey of India Quarter Inch and One Inch scale maps. But locating sites where only the vaguest location had been described was often little better than educated guesswork (and even the two map series occasionally diverged on detail).

Publishing the gazetteer

My work on the publication of the gazetteer took two years spanning 1980 and 1981, with French funding secured by Jean-Claude Gardin. The first year was spent mainly in the UK near Southampton with frequent visits to Paris to avail myself of the services of the CNRS and the Musée Guimet in Paris, as well as to London where I used the libraries of SOAS and the (then) India Office Archives and Library in Waterloo. 1981 was spent back in Afghanistan—now under Soviet occupation—to complete the work that was published in two volumes in 1982 in a French Foreign Ministry imprint in Paris (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: 1st Edition of the Archaeological Gazetteer of Afghanistan, in 2 volumes (1982)

Limitations: What the gazetteer doesn't do

I set the Timurids (14th century) as a chronological end point for the gazetteer, because after this period virtually every modern town and even many large villages would qualify as sites. Including all these would have made the gazetteer unwieldy. Thus, many important later monuments, such as the Bagh-i Babur in Kabul and the Takht-i Pul near Mazar-i Sharif, without which no study of Islamic architecture in Afghanistan would be complete, are missing from the gazetteer. But one must stop somewhere, otherwise there would be no reason for not including twentieth century monuments such as the Darulaman palace or the buildings at Paghman. That being so, many sites for which a dating is not known, e.g. sites I record simply as ‘fort’ or ‘ruins,’ may also be from later periods.

Organisational points

All sites are listed in alphabetical order. This might not be ideal in all cases: a listing by region or date, for example, might be more relevant for a certain researcher. However, modern regional boundaries do not necessarily reflect historical reality, historical boundaries even less so, and in all cases can move and have done so: Greek Bactria, for example, does not correspond to, say, medieval Tukharistan and still less modern administrative boundaries. I would suggest as a starting point for researchers interested in a specific region, the regional maps, from which they can consult the sites by site number. Listing by period is even less practical: interpretation of date changes, and multi-period sites would result in needless repetition of site entries. The starting point here for researchers therefore would be the period maps or, better, the chronological index in Appendix 1.

Perhaps the greatest limitation is that the gazetteer simply stops at the modern borders of Afghanistan, borders which, by and large, are irrelevant for the periods covered by the gazetteer. In no place do the modern borders follow natural boundaries; even the Oxus, like any major river such as the Nile or Indus, is hardly a boundary, but serves rather to bind cultural groups than separate them. Not only the much-vaunted Durand line but every single border of Afghanistan divides ethnic, linguistic, cultural, historical and geographic units. Much of the information compiled in the gazetteer usually represents only a part (often a small one) of a picture that encompasses a far wider area. It was, therefore, after much agonising over names, locations, what to include and exclude, how to organise the data, and much else, that the first edition came into being in 1982.

The new edition

Initially, I had planned to bring out regular supplements to the 1st edition, to include ongoing and new fieldwork findings, along the lines of the Index Islamicus catalogue of publications. But once Afghanistan was closed to Western researchers, supplements to AGA became a moot point. My own work, moreover, had taken me elsewhere, although I kept an ongoing – if sporadic – record of relevant new publications. Things changed after the political thaw in the early 2000s following the fall of the Taliban: Afghanistan cautiously opened once again to limited fieldwork. Observing a new interest in Afghanistan’s cultural heritage (also stimulated by a worldwide touring exhibition of treasures from Afghanistan’s National Museum), I revived my long-shelved plan to produce a 2nd edition, now with a new publisher, Oxford University Press, and in a consolidated single volume.10

Sadly, no electronic version of either the original manuscript or the published volumes of the 1st edition had survived. With OCR systems not advanced enough to recognise diacritical marks, I had to have the 1st edition retyped by a professional typist. (Some years later I discovered I could have saved my money: most of the Catalogue was downloadable for free on a website I traced back to the US State Department! I was acknowledged and flattered, but never consulted. That website has now been taken down, but another website has appeared that copies much of my original Gazetteer, word for word. You guessed it: Wikipedia).

The second challenge lay in being far away from the magnificent library of the DAFA in Kabul. A few days in the superb library of the Afghanistan Institute in Switzerland made up for some of this, but I was not equipped with the resources to go through the many online repositories. Thus, even the revised bibliography is still far from comprehensive.

A new challenge I faced when making the 2nd edition, was to figure out how to add previously unrecorded sites to the catalogue. I decided to maintain the alphabetical order used in the 1st edition, and to develop a Supplement that would include additional sites, with a new numerical system beginning with the number “2000” to differentiate it from the numbering in the 1st edition. This also means that users should ideally reference site numbers rather than page numbers in both editions.

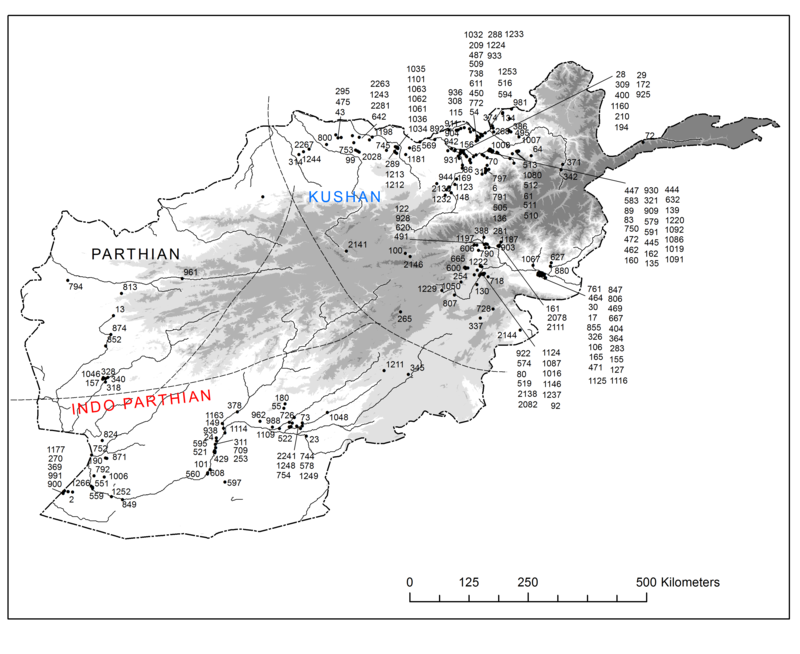

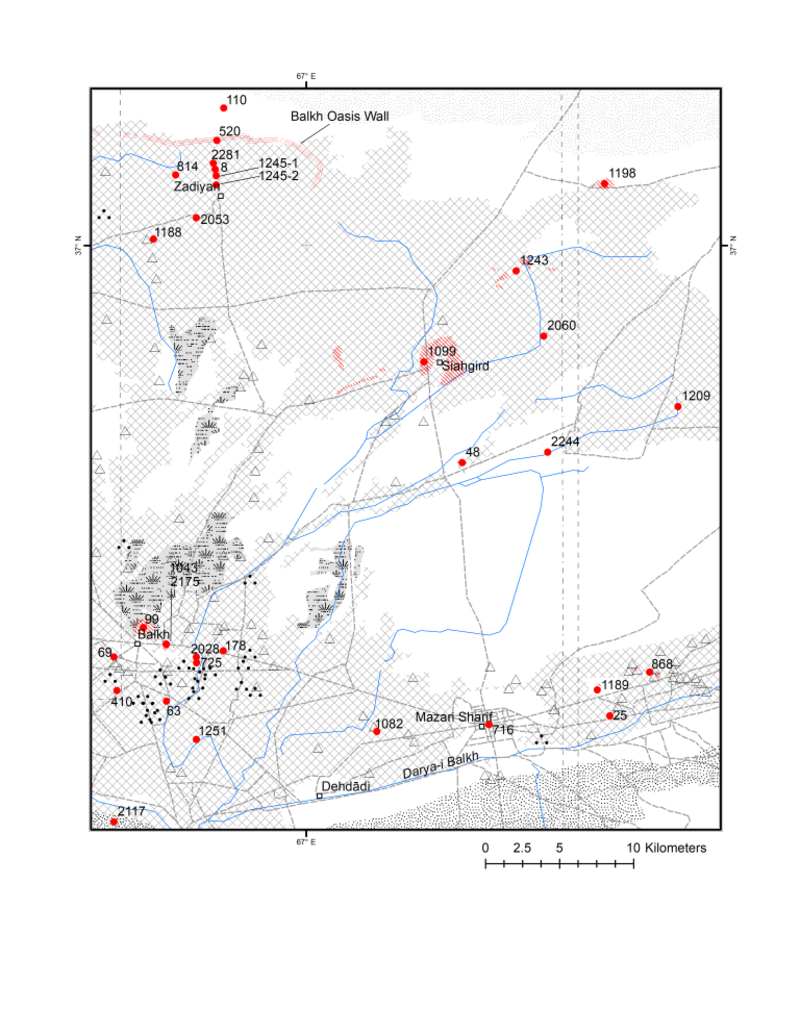

I now lacked the ballroom of the magnificent British Embassy in Kabul which I had covered with the complete set of the 1:100,000 maps (a carpet which, I suspect, no other ballroom in the world has experienced), to pinpoint sites, and all features of geographical and archaeological interest which I had laboriously traced off by pencil onto tracing paper. Luckily, the Afghan Heritage Mapping Partnership (AHMP), a project supported by an institutional grant from the US Department of State and the US Embassy in Kabul with a team based at the University of Chicago (Fig. 3), came to the rescue.

Fig. 3: Warwick Ball (centre), with the AHMP team in Chicago, Becky Siegfried, Tony Lauricella, Emily Hammer, Kate Franklyn (left to right), in 2016

Following a visit in 2016 they generously offered to create entirely new sets of maps, as well as to generate new coordinates for all the sites, based on their high-resolution satellite images (see Figs 4 and 5). The satellite images were supplied by the US State Department, and so I came full-circle!

Figs 4 and 5: Maps in the 2nd edition

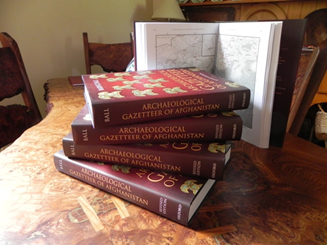

The 2nd edition was published in 2019 (Fig. 6). The original took four years from inception to publication; the 2nd edition took 15 years, despite all the advantages of modern computer and digital technology.

Fig. 6: 2nd Edition of Archaeological Gazetteer of Afghanistan (2019)

A 3rd edition of AGA?

No publication like this is ever finished. The recent publication of the Helmand-Sistan Project, for example, has added enormously to the number of sites recorded, while the forthcoming publication of the German surveys in the Herat region will add many more. The work of the AHMP in Chicago is, of course, to record many thousands more sites than the ones I could possibly have recorded. Invisible East has identified dozens of sites mentioned in documents that have come from pre-Mongol Afghanistan that are not in the gazetteer either. The technological changes in the 37 years between the first and second editions – not to mention the political changes in Afghanistan in the same period – are nothing compared to a hypothetical 3rd edition. Clearly, I would no longer be around if such a 3rd edition appeared after a similar time gap.

A new edition would need to be ongoing, online, and multi-authored. I hope my historical exposé of the creation and evolution of the AGA can serve as inspiration for those who may like to follow my lead in this, and agree with me that this is a hugely important and worthwhile undertaking for anyone interested in Afghanistan’s history and heritage.

Key references (not mentioned in the body of the blog)

Ball, Warwick avec la collaboration de Jean-Claude Gardin, Archaeological Gazetteer of Afghanistan/Catalogue des sites archéologiques d’Afghanistan. Tome I, Tome II. Asie Centrale. Synthèse no 8. Paris: Editions recherche sur les civilisations, 1982.

Ball, Warwick. “Project for an Archaeological Gazetteer of Afghanistan.” Afghan Studies 3 & 4 (1982), 91-96.

Fleming, David. “Cultural Imperialism on £10 a day: The short, tumultuous history of the British Institute of Afghan Studies 1972-1982.” Afghanistan 3, 2 (2020), 174-201.

Luchtanas, Alekseijus and Ramunè Butrimaitė, Arijų protėvynės beieškant (Antroji Lietuvos archeologinė ekspedicija Afganistane)/In pursuit of Aryan homeland (2nd Lithuanian archaeological expedition in Afganistan), Lietuvos Istorijos Studijos 22 (2008), 163-77.

Trousdale, William B. and Mitchell Allen. The Archaeology of Southwest Afghanistan. Volume 1: Survey and Excavation. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2022.

Notes

1 The launch of the Balkh Art and Cultural Heritage project (BACH) at the University of Oxford, co-directed by Arezou Azad with Edmund Herzig before Prof Azad went on to lead the Invisible East programme.

2 The inauguration at the Institute of Archaeology of the Central Asian Seminar Group.

3 https://isac.uchicago.edu/research/camel/afghan-heritage-mapping-partner... https://irangazetteer.humspace.ucla.edu/

4 Gazetteer Site 583.

5 Gazetteer Site 95.

6 Gazetteer Site 166.

7 Gazetteer Sites 256-9.

8 Gazetteer Site 404.

9 Gazetteer Site 792.

10 In the meantime, a drastically reduced version of the Gazetteer had been incorporated into Warwick Ball, The Monuments of Afghanistan: History, Archaeology and Architecture, London: I B Tauris, 2008.

About the author

Warwick Ball is an independent scholar who has worked in and on Afghanistan for more than 40 years. He lives in the Scottish Borders.