Rural Administration, Society and Economy in the Bamiyan Area - Part 2

Rural Administration, Society and Economy in the Bamiyan Area: The Story told by the Barāt Documents in the Bamiyan Papers

by Arezou Azad, 29 November 2022

** Contents of this blog will appear in a volume that is currently being prepared for publication by Arezou Azad and Pejman Firoozbakhsh. **

Part 2: "The Findings"

1. What the barāts tell us about the Khurāsānī fiscal system in the Bamiyan area

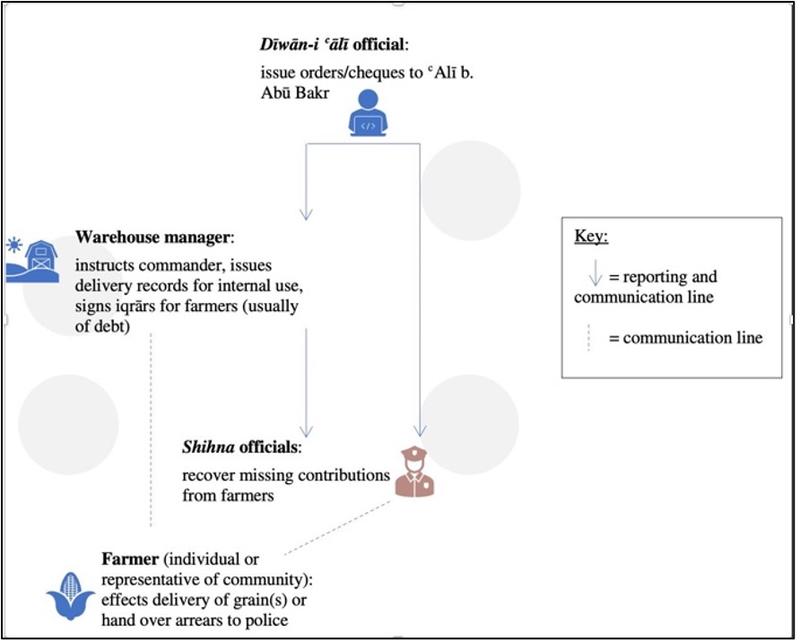

The network of people involved in the Khurāsānī fiscal system in Bamiyan is very clear from the barāt documents. It concerns farmers (barzigarān) and local police officers (shihna) at estate level, and warehouse officials and ministerial financial officials at the central level of the Bāmiyān sultanate of the Ghurid administration. Readers should not assume that farmers had low statuses, as Ann Lambton (1988: 353) might have had us believe (she translated barzigar as “husbandman, peasant, cultivator”). The illustrious titles attached to their names, such as sarhang (commander), faqīh (legal scholar) and muḥtasib (market overseer) rather give them a very different quality: namely that of the gentleman-farmer, of the posh sort. An alternative reading may be that the word barzigar has a possessive value (if you add the generally unwritten iḍāfa) in which case the reference may be to two people rather than one, as in “the barzigar of the commander,” rather than the “barzigar, [and] commander.”

We also learn about the status of the warehouse manager, who was far from insignificant in the state hierarchy. He was probably at the top of the second tier of the administrative hierarcy, enjoying being addressed with the honorifics, naqīb and iʿtimād al-mulk (“the trusted one of the realm”). The latter honorific is understandable if we consider the large amounts of agricultural product that Abū Bakr and ʿAlī were administering. Abū Bakr’s power is also demonstrated in the documents in which he instructs local police officials to collect outstanding tax remittances directly from tax defaulters.

Diagram 1: Relations between officials based on anbār archive in the Bamiyan Papers

2. The Economic Outlook

Volumes of tax deliveries on donkey transport

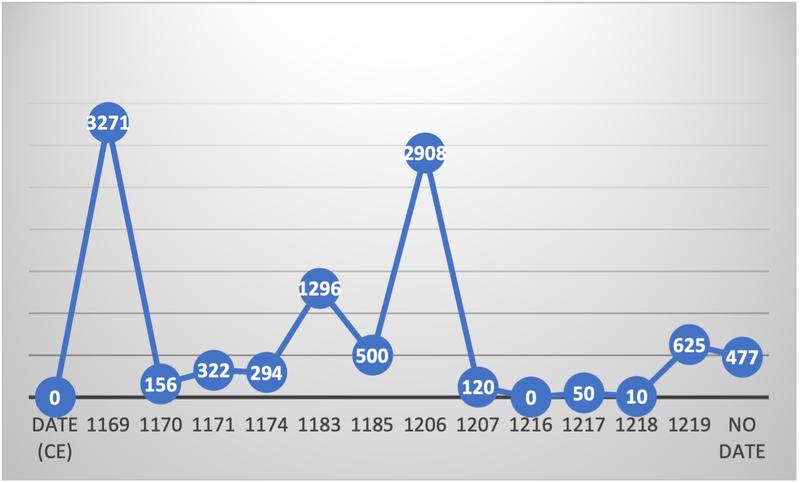

Across the deliveries to the warehouse of Abū Bakr and his son in the 37 years between 1169 and 1219 CE, the highest volume of annual delivery was 3 tonnes in one given year (1169 CE). It is highly unlikely our set is complete, and the amounts would almost certainly have been much higher. The largest delivery is as high as 3,271 mann of grain (ca. 3 tonnes). Such deliveries was made by or on behalf of a group of people who represent a village or estate (Per. dih). A brief word on mann equivalents: mann is attested both in medieval times and is still in use today, and its value has changed across time and space. We have applied the 0.833 Kg equivalent based on the analysis of Nabipour and Hinz (Nabipour 1973, p. 3); the rates change in the early 14th century after the Ilkhan Ghazan Khan’s reforms.

Diagram 2: Volume (in mann) of annual tax remittances (1 mann = 0.833 Kg)

Wheat appears in more than 40% of the archive documents in which commodities are listed, and deliveries were made in significant amounts with an average of 161 mann per delivery (i.e. 134 Kg). If we apply the general rule that donkeys can carry about 50 Kg, this means that an average delivery would involve 2-3 donkey loads. The sizes of the deliveries varied widely and could be as little as one donkey load (for 24 or 45 mann of wheat), and as much as 10 donkey loads (for 672 mann of wheat).

Extrapolation of yield data

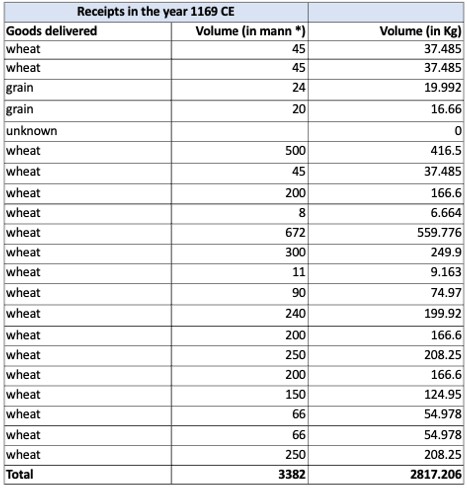

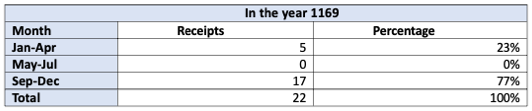

Because our documents are so random and patchy, a more accurate picture may be taken from the year 1169 CE in which receipts were issued in sufficient numbers that some tentative economic data can be extrapolated from them.

Diagram 3: Volumes of commodity taxes paid according to the receipts dated 1169 CE (1 mann = 0.833 Kg)

From the tax remittances it is possible to estimate how much the gross harvest yield was per estate or collaboration. To establish the harvest yield, we needed to estimate the tax rate applied to the yield. Without any such data in the Bamiyan Papers (we know there were rates, but not their specific values), comparable data need to be sought on land tax rates in the narrative sources. Lambton, who used narrative sources and curated compilations of Seljuq administrative letters (the latter are less reliable than actual documents), explains that in 10th-century Fārs pasture-tax (marāʿī) and tax on mines was set at the rate of 20% (plus a water tax being levied). Kharāj was assessed in three ways, she adds: 1) an amount due calculated based on the extent of the area by measurement (masāḥa), 2) or on the basis of actual produce (muqāsama), or 3) as a lump sum not based on either measurement or actual produce (muqāṭaʿa). Lambton differentiates the muqāṭaʿa from the “revenue farm,” where the right to farm the taxes of a district was put up to auction and sold to the highest bidder, which was “injurious to agricultural prosperity.” The rates varied in different parts of the province depending on factors like levels and types of irrigation, while vineyards and plantations were apparently exempt from land tax.

The patterns of receipt issuance over a given year also point to the seasonality of tax payments. In 1169, 77% of the receipts were issued just around the time of the harvest in October-November. None were made in the summer months at all, while a small number of receipts was issued in early Spring.

Diagram 4: Tax Schedule

The Spring deliveries may have been repayments of loans received by the barzigars for the previous season: one of the relevant documents in the set concerns the delivery of grain by 11 different representatives to the amount of 306 mann of grain which are destined for the anbār-i ḍakhīra (granary). Thus, the harvest season in October-November would have been a busy time of year for farmers and storehouse managers alike: farmers for having to bundle up their yields and transport them to the central storehouse, and for Abu Bakr b. ʿUmar for storing and logging the deliveries, and then transporting them further for the commodity trade.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, the Bamiyan Papers do not include documentation that can show us what the storehouse did with the yields exactly, i.e., where they were transported, to whom, or for what purpose. Despite this, the Bamiyan Papers have proven themselves to be of significant historical value for giving us a first-time view of the administration of state at the provincial and rural levels in this eastern part of the medieval Islamicate world.

I, for one, am particularly struck by the levels of literacy, bureaucracy, and professionalism of the staff as displayed through the archives of this provincial and local administration system. I am especially enticed by the documentary evidence for the governance mechanisms that were in place to prevent corruption, and for dealing with suspicions of corruption once they were transmitted up the chain of command. There are many more such stories buried in these documents, some of which we will look forward to presenting in our forthcoming book.

---

About the author:

Arezou Azad is Senior Research Fellow at the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Oxford, PI and Director of the Invisible East programme.

---

Selected bibliography

Bosworth, C. Edmund. “Abū ʿAbdallāh al-Khwārazmī on the Technical Terms of the Secretary's Art: A Contribution to the Administrative History of Mediaeval Islam.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 12/2 (Apr.,1969).

Hinz, Walther. “Das Rechnungswesen orientalischer Reichsfinanzämter im Mittelalter,“ Der Islam (1950), 1-29.

Hinz, Walter, Die Resala-ye Falakiyye des 'Abdollah Ibn Mohammad Ibn Kiya al-Mazandarani. Ein persischer Leitfaden des staatlichen Rechnungswesen (um 1363) (Wiesbaden, 1952).

Lambton, Ann K.S. Landlord and Peasant in Persia: A Study of Land Tenure and Land Revenue Administration (London: I.B Tauris, 1991 [1953]), xiii-xxxi, 1-76.

Lambton, Ann K.S. Continuity and Change in medieval Persia: Aspects of Administrative, Economic and Social History, 11th-14th Century (London: I.B. Tauris, 1988).

Nabipour, Mirkamal. Die beiden persischen Leitfaeden des Falak ʿAlā-ye Tabrīzī ueber das statliche Rechnungswesen im 14. Jahrhundert, Goettingen 1973.