Document of the Month 11/24: A Hidden Threat

Classmark: NLI, Ms.Heb.8333.18=4

A Hidden Threat from the Eleventh Century: Peasants Stand Up to Their Landlord

by Ofir Haim

"If this happens again and in the same manner, we will not be able (to cultivate) the master’s lands."

Does this sound like a threat to you? If so, you are right! This striking declaration is drawn from an eleventh-century letter written in Early New Persian, found in central Afghanistan and currently housed at the National Library of Israel (Ms. Heb. 8333.18=4). But what would drive medieval peasants to threaten their landlord? To understand this, we need to delve into the letter’s contents and uncover the story behind this bold statement.

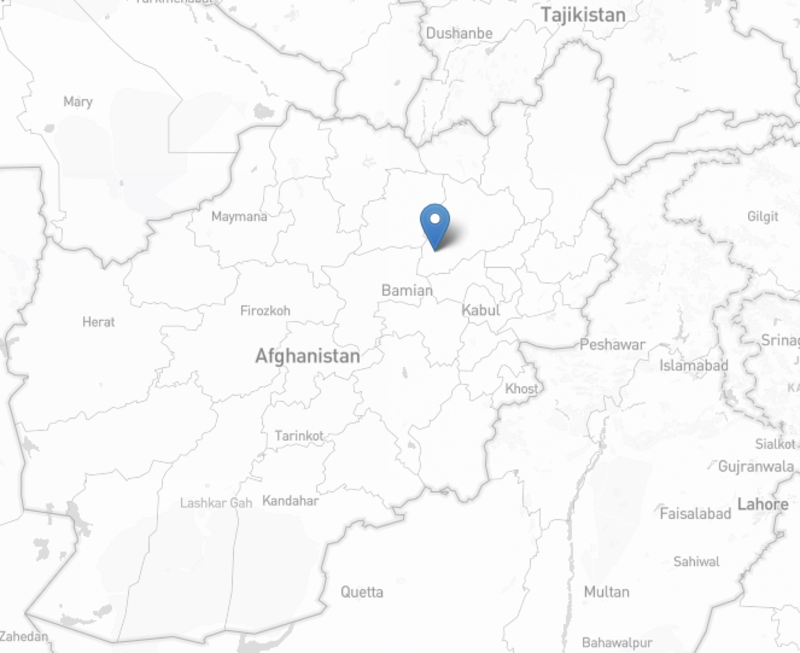

The letter was sent from the community (jamāʿat) of the villages Khustgān and Angār, which can be identified with two neighbouring villages in the present-day Baghlān province, about 80 km northeast of Bamiyan.

Map showing the location of the neighbouring villages Khustgān and Angār, in the present-day Baghlān province in Afghanistan

The recipient is addressed as “the master” (khwāja), who owns lands in these villages.

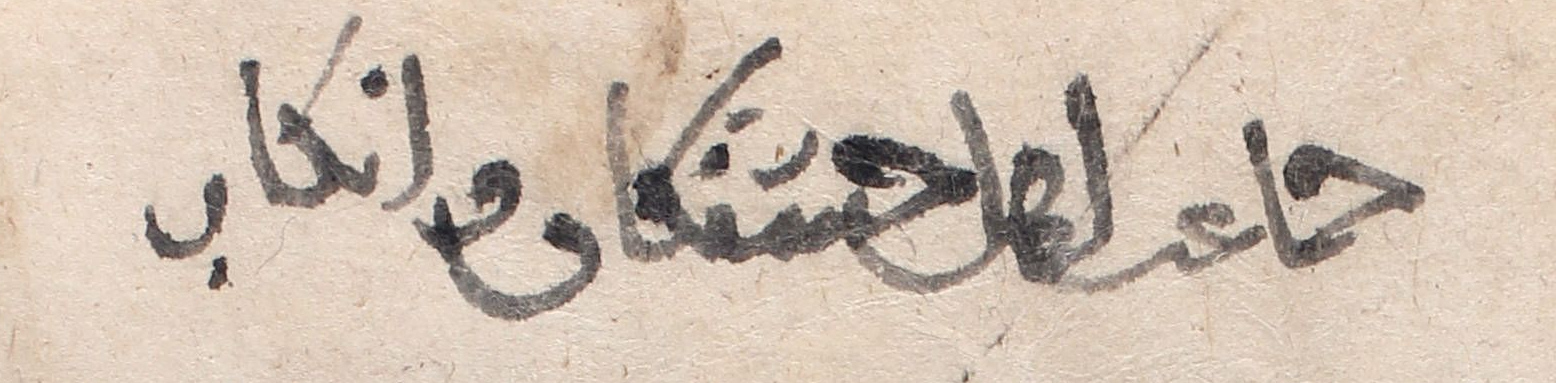

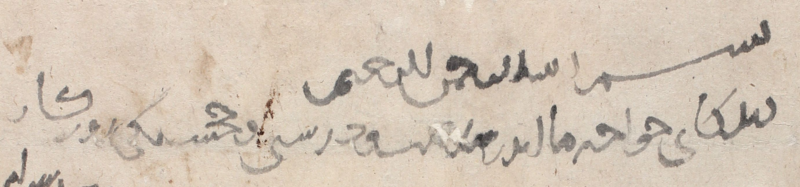

Detail of Jerusalem, National Library of Israel, Ms.Heb.8333.18=4, showing the opening lines of the letter

In the letter, the peasants complain about irregularities in the transportation and sale of the yield of grapes and pomegranates by the landowner’s representative who was sent by a certain ʿAlī, possibly an employee of the landowner. The representative is referred to as “peon” (piyāda). While the conventional meaning of piyāda is “foot-soldier,” it should be interpreted as a wage labourer dispatched to the village on behalf of the landowner. It is important to note the author’s critical tone, which could also imply connotations of “ignorant” or “unskilled.”

The peasants protest against the misconduct and unprofessional behaviour of the representative, who ordered the peasants to “send out the grapes” and refuse to accept a certain individual named Nisā (or Nasā). The representative also claimed that the “master” had given him the financial means to rent camels to ensure a speedy transport of the agricultural produce from the villages. However, due to what the peasants perceived as the representative’s lax action, the grapes never arrived at their (unspecified) destination, the cargo was ruined beyond salvage and the sale nullified.

The senders further state that a certain individual, probably the same representative, sold 100 sweet pomegranates for a mere three dirhams. The remonstrative tone of this part of the letter implies another attempt by the villagers to discredit the representative. They clearly felt that the sum of three dirhams was too low. Additionally, the representative took his “share” (of his wage?) without the villagers being present, which seems to have been a breach of protocol.

What can be inferred from this fascinating letter so far? The following insights may be offered:

(1) It reflects the trajectory of the agricultural produce cultivated on private lands, showing that the produce was collected, loaded onto camels in the village, and transported to the marketplace to be sold.

(2) It provides evidence of a structured and organised process for the collection of agricultural produce, likely established through a contractual arrangement between the landlord and the peasants, outlining the distribution of the yield and the responsibilities of each party. The letter reveals, for example, that the transportation costs were covered by the landowner and provided by his representative, who also supervised the loading and safe arrival of the produce.

The breach in the contractual arrangement is what led the tenants, who refer to themselves as “servants” (sg. chākar), to express concern that recurring issues may prevent them from further cultivating the master’s lands, which would cause the landowner significant financial damage. Since “the master has many servants there” (ānjā khwāja-rā chākar bisyār-ast), the landowner should inform in advance the next person sent to their community about the contractual arrangement to avoid future misconduct.

This mild threat by the tenants demonstrates the landowner’s dependence on them for his economic success. Any breach of contract by the landowner or his representative would result in a severe reaction by the tenants. Without their labour, the landowner would not be able to make a profit from his land. The tenants’ ability to complain and threaten to sever ties, shows that the landowner could not easily replace them, causing a vacuum in land cultivation and a consequent loss of revenue.

In conclusion, this letter provides a rare glimpse into the power dynamics between landowners and tenants in the eleventh-century Islamicate East. The detailed complaints and mild threats illustrate the peasants’ awareness of their importance in the agricultural economy and their ability to negotiate a fair treatment. This document not only sheds light on the economic practices of the time, but also highlights the intricate relationships that sustained medieval society. Through such historical records, we gain valuable insights into the complexities of land management, tenant-landowner relations, and the agricultural processes that underpinned the economy of the medieval eastern Islamicate world.

-

جماعت اهل خستگان وانگار

-

بسم الله الرحمن الرحیم

-

زندگانی خواجه ما اندر سلامت و درستی و خجستگی روزگار

-

رقعه نبشتيم از حال سلامت و الحمد لله وحده و الصلوه علی رسوله

-

اما اندر وعد که علی بیامذ وپیاده فر ما موکل کرذ که انگور

-

بیرون کنیذ و محضر نبیسیذ که ما نسا را ایده الله نخواهیم

-

و خواجه مرا زر دادست از سبب کری اشتر را تا پیش از همه

-

ناحیت انگورها خویش بیرون کردیم تا بر ما همه ناچیز گشت

-

و بزمین فرو شذ ومقدار دو ماه برهایی بماند وآن چند

-

بستان صد نار شیرین بسه درم فروختست و برها بخش اوی

-

کردست و ما حاضر نبودیم خواستیم تا بداند و اگر

-

دیگر فرین گونه بود و بدین مثال ما جایها خواجه نتوانیم

-

آنجا خواجه را چاکر بسيارست هرک آنجا آید گوید همه سیم

-

و غول سختیم چهار و نیم من آمد تا دانسته آید

-

و الحمد لله وحده

-

The community of the people of Khustgān and Angār

-

In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate.

-

(May) the life of our master (be long) in peace, good health and good fortune.

-

We wrote the letter in a state of peace, praise be to God alone, and His blessing upon His messenger.

-

As to the set time when ʿAlī came and appointed over us a peon (who told us to):

-

“Send out the grapes and write a report (saying): ‘We do not want N.sā, may God support him.’

-

The master has given me gold for hiring camels.”

-

We sent out our grapes first in the region. But all our fruit was ruined and

-

dumped to the ground; a total of two months of fruit was left (behind). And as for (the yield from) those few

-

gardens, he has sold one hundred sweet pomegranates for three dirhams, and has taken his cut from the (sale of the) fruit

-

in our absence (lit., ‘and we were not present’). We wanted to inform him (about this matter). If

-

this happens again and in the same manner, we will not be able (to cultivate) the master’s lands (lit., ‘places’).

-

The master has many servants there; whomever he sends there, he should tell (him that).

-

We weighed all the produce(?), (it) amounted to four and a half mann. He should take notice of this.

-

Praise be to God alone.

For the full publication, see Ofir Haim, “Jews, Landlords and Peasants in the Ghaznavid Bamiyan Hinterland. A Private Archive from the Eleventh Century (Bamiyan Papers/Afghan Genizah),”Atiqot 112 (2023): 201–24.

Cite this article

Haim, O. 2024. “A Hidden Threat from the Eleventh Century: Peasants Stand up to Their Landlord.” Document of the Month. Invisible East. doi: 10.5287/ora-pdao0mzxv.

About the author

Ofir Haim is a postdoctoral fellow at the Mandel Scholion Research Center, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and an external adviser with the Invisible East team.

The online series, Document of the Month, presents some of the most interesting and revealing medieval documents from the desks of Invisible East researchers and their colleagues worldwide. Each piece in the series is dedicated to a single document or a closely related group of documents from the Islamicate East and tells their story in an engaging and accessible way. You will also find images, editions and translations of the documents. If you would like to contribute to the Document of the Month series, please, get in touch with Nadia Vidro.

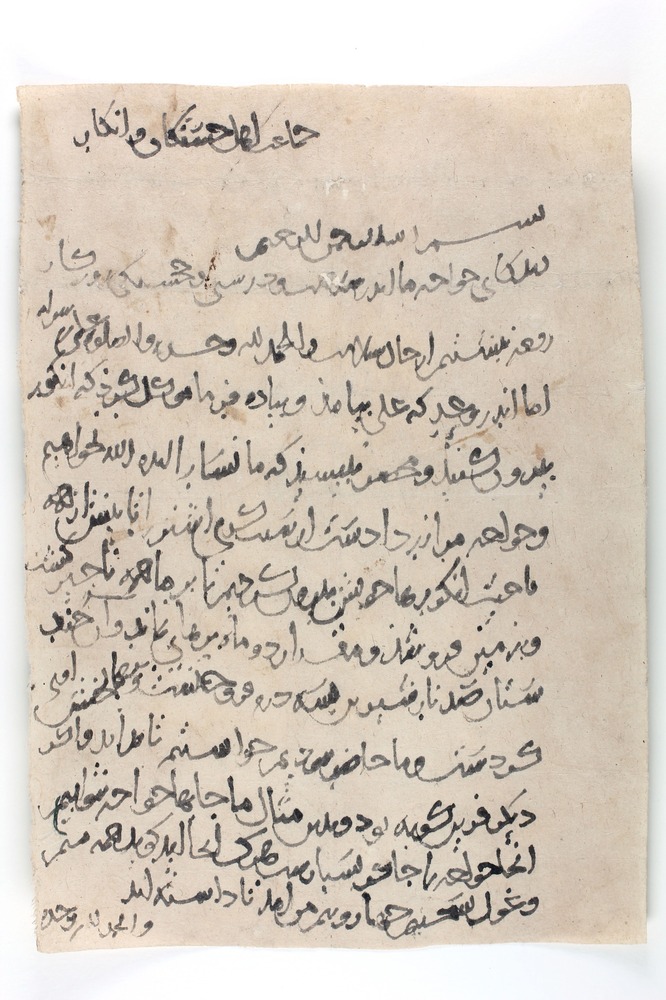

Jerusalem, National Library of Israel, Ms. Heb.8333.18=4 (courtesy of the National Library of Israel).

31.8 (height) by 23.3 (width) cm, 8 fold lines, complete, black ink.

Full details of the letter, including a high-resolution image, can be found in the Invisible East Digital Corpus