by Mateen Arghandehpour, February 2025

The fourteen extant late 11th- and early 12th-century legal documents from Yarkand in Arabic and Old Uyghur were published separately by Huart (1914), Erdal (1984) and Gronke (1986). One of my first tasks as part of the Invisible East Programme was to read these articles and create digital copies of the documents to match the format and standard of the Invisible East Digital Corpus. Reading the three articles pitted me against technical and linguistic challenges. I talk more about these below, but what interested me more than the challenges I had to overcome was the documents themselves – how the arbitrary fancy of their 20th century colonial owners resulted in the eventual loss of the original documents and the partial survival of their facsimiles!

The Yarkand collection and its history

The documents were discovered in 1911 in a garden on the outskirts of modern Yarkand, in today’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China. They later found their way into the hands of the Director-General of Archaeology in India who allowed Sir Denison Ross, a specialist in languages of the Middle East, Central and East Asia and the first Director of SOAS, to photograph them. In a note, reproduced in Erdal (1984, p. 261), Denison Ross explains that he saw a total of 15 papers: seven in Arabic and eight in Old Uyghur, a Turkic language. The original documents remained in India and their current location is unknown. Another scholar, Sir Gerard Clauson, who had been working on these texts, passed away before he could publish his findings. They were then passed on to his literary executor, Prof. V. L. Ménage, who made them available to the documents’ eventual editors Marcel Erdal and Monika Gronke. Erdal published his work on seven Old Uyghur documents in 1984 and Gronke hers on five Arabic ones in 1986, both with facsimiles. In the 1980s, most of Denison Ross’ original photographs were held in the SOAS library in London; the location of the rest was unknown. I made an inquiry of my own in December 2024 and was told that the library had recently undergone renovation and its collections were as yet in disarray.

At least three more documents from Yarkand were discovered separately by a French scholar, Paul Pelliot, who took them to France. Huart received these three Arabic documents and published them in his 1914 article. The location of the French papers is unknown, though the Arabic Papyrology Database (APD), suggests the Louvre archives. Unfortunately, Huart’s article does not provide images of his documents, and he does not transcribe the Old Uyghur lines, except in a couple of places where he provides partial translations and transliterations. This can be all the more frustrating for parties interested in the Old Uyghur elements of these texts, which would have been found in the witness statements of Huart’s texts II and III.

The Yarkand documents were found at a time when Russian scholars were actively collecting Old Uyghur (and other) documents to form the Serindia Collection from the eastern part of present-day Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region and Gansu province of China. This collection now contains just over 6,700 documents and is kept in St. Petersburg, Institute of Oriental Manuscripts of the Russian Academy of Sciences. The existence of other Old Uyghur texts and texts in Arabic script in this collection is promising and further studies may yield more archival documents pertaining to this culture and period.

As historic evidence, the Yarkand documents open a window into the earlier years of the Eastern Qarakhanid Khanate (1041 – 1210 CE). Their dates coincide with a period during which the Eastern Qara Khaqan (ruler) was running a campaign to spread Islam to the Turkic nomads of the Tarim Basin and was enlarging its effective army and population. It may not be accidental that many of the documents in the corpus mention people with military titles. Moreover, the documents are a testament to the gradual adoption of Muslim legal procedures and norms, as well as of the use of Arabic language and script in legal contexts. To learn more about the adoption and adaptation of Muslim document writing practices in Yarkand Old Uyghur deeds, read this Document of the Month article.

Transition to the Invisible East Digital Corpus

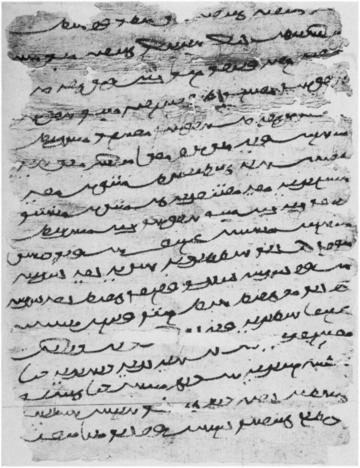

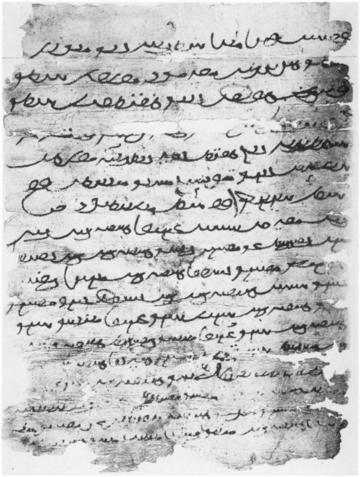

As mentioned above, one of my tasks in the Invisible East Programme was to create digital copies of documents edited by Huart, Erdal and Gronke. As I began work on their articles, I immediately noticed that my first challenge was a technical one. The facsimiles of the documents as they appear in Erdal and Gronke’s articles are of poor quality, and it can be hard to determine if certain photographs are showing the verso of a document, the lower half of a folio, or an entirely new folio altogether. I spent some time looking these over and made judgements about these folios, which were then double checked by Prof. Azad before we decided how to present the details on the Invisible East Digital Corpus (IEDC). For example, Figure 1 shows two separate photographs from Erdal’s article, Turki 4 and Turki 5. Erdal says that they have previously been ‘joined together’ by previous scholars. I initially thought this meant that they were images of two separate sheets that scholars had presumed a connection between through their contents. However, by observing the damage around the sides of both documents, I determined that these images represent two sides of the same folio. See, for example, how the triangular rip on the top of Turki 4 and the leaf-shaped hole with a horizontal “tail” on the right between lines 4 and 5 are reflected in the bottom part of Turki 5. Notably, the page was turned vertically rather than horizontally when the scribe began writing on the other side. Following this analysis, Turki 4 and Turki 5 are included in IEDC as recto and verso of the folio.

Figure 1. Turki 4 (left, recto) & Turki 5 (right, verso); photographed in 1910s by Sir Denison Ross; images taken from Erdal (1984, pls. I, II).

My second challenge was a linguistic one. While Gronke’s Arabic transcription and diacritics are easily transferrable to IEDC’s style, the same cannot be said for Huart, who uses an outdated style. Erdal presents a different kind of challenge because he uses a specialised form of diacritics for Old Uyghur but does not cite his style or denote what pronunciations his specialist symbols are meant to represent. In a meeting with Prof. Azad, she advised that it will be best to forego uploading this transcription until a specialist in Old Uyghur can have a look at it and advise our team regarding the transcription style and other linguistic notes that we would be unfamiliar with.

Having digitised hundreds of documents since, the Yarkand documents have remained as some of my favourites. Since being dug up in a Yarkand garden in 1911, the documents have travelled across continents, gotten lost, found in the form of pictures and then lost again. Erdal and Gronke have published a total of 12 of Sir Denison Ross’ 15, leaving one Old Uyghur and two Arabic documents yet to be found. There is a chance that Pelliot’s documents will resurface, not to mention the many more that survive in the Serindia Collection, giving more evidence for the unique cultural status of people living in the Eastern Qarakhanid Khanate in the 11th and 12th centuries.