Tracking the Qur’ān in European Culture

The Qur’ān refers to umm al-kitāb, the “mother of the book” (Q 13:39, 43:4), the primordial scripture from which Torah, Gospel and Qur’ān were derived. The relations between the holy books of Jews, Christians and Muslims have ever since been a subject of discussion and dissention among followers of the three Abrahamic religions. I am interested in on how European Christians perceived and represented the Muslim holy book between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries. This research is part of a major European research initiative, the ERC synergy project “The European Qur’ān” (euqu.eu), which attempts to place European perceptions of the Qur’ān and of Islam into the fractured religious, political, and intellectual landscape of the period from the twelfth to the early nineteenth centuries. My presentation will conclude with an overview of this project and introduce the members of the Nantes EuQu research team, post-doctoral researchers and PhD students.

Medieval Christian authors writing in Latin often portrayed the Qur’ān as a bogus revelation made by “Mahomet”, a charlatan who feigned prophecy and concocted fake miracles in order to trick “Saracens” into believing him. Various twelfth-century authors affirm that he wrote his book of “laws” (which some of them called the “Alcoran”) and tied it to the horns of a bull, who “miraculously” appeared as Mahomet was preaching to the Saracens. The iconography of the bull with the Alcoran on his horns had a long life, in manuscripts and printed books from the 13th to 17th centuries. This piece of medieval “fake news” was meant both to denigrate a rival religion and to explain its success.

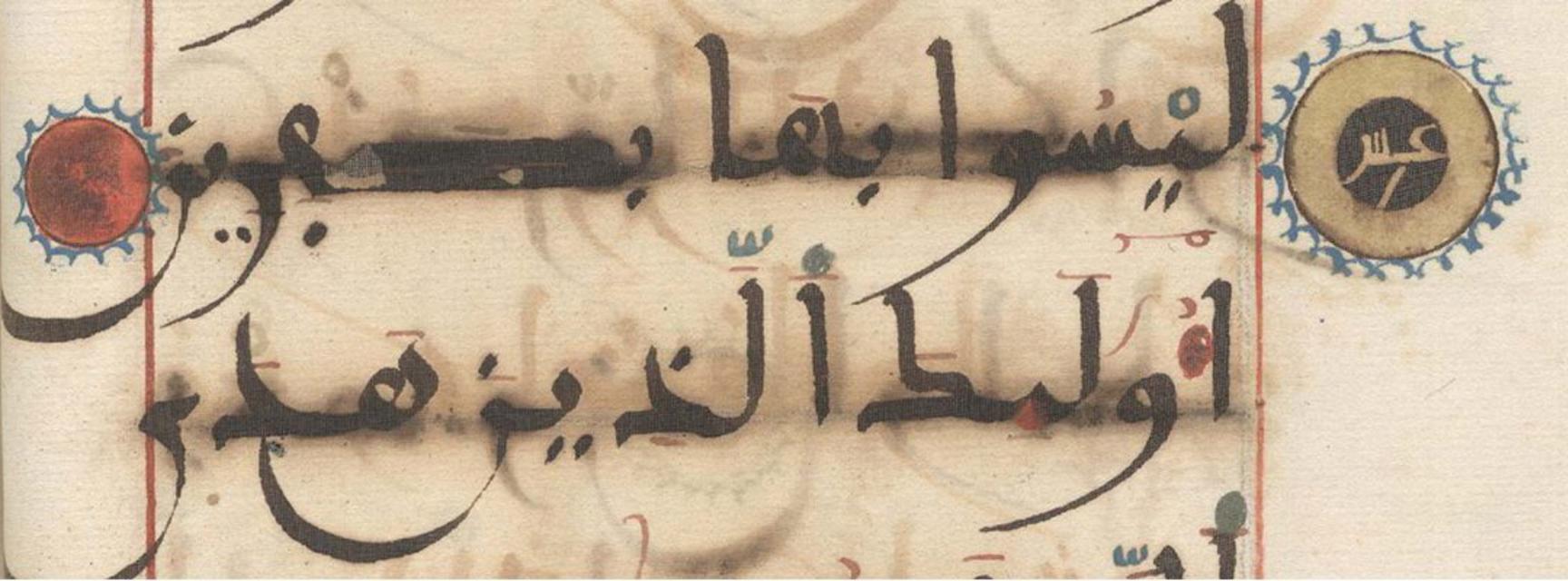

At the same time, some European Christians took a more scholarly approach to the Qur’ān. Englishman Robert of Ketton went to Spain to learn Arabic and study astrology; Peter, Abbot of Cluny, hired him to translate the Qur’ān into Latin. The translation, finished in 1143, became the most important single text in Latin for the study of Islam; four centuries later, in 1543, is was published in Basel with a preface by Martin Luther, making it widely available to European intellectuals. In the liminal texts (introductions, prefaces, annotations, etc.) that accompanied Ketton’s translation in medieval manuscripts and the 16th-century printed editions, we see a profound ambivalence towards the Muslim holy book. While it was standard to denounce it as a bogus revelation by a false prophet, at the same time it was taken seriously. The page layout in many of the manuscripts and in the printed editions were similar to those used for biblical texts, visually according to the “Alcoran” the status of scripture. Moreover, like biblical texts, the text was accompanied by rubrics and glosses meant to help the reader understand the text. While some of these commentaries oriented the reader to hostile interpretations of the Qur’ān (pointing out, for example, the differences between Qur’ānic and Christian conceptions of Christ), others expressed agreement and admiration. The Qur’ān provoked hostility and incomprehension in its European readers, but also at times sparked curiosity and admiration.

About the speaker

John Tolan works on the history of religious and cultural relations between the Arab and Latin worlds in the Middle Ages and on the history of religious interaction and conflict between Jews, Christians and Muslims. He studied at Yale (BA classics), University of Chicago (MA & PhD history) and the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (Habilitation à diriger des recherches: HDR). He has taught in various universities in North America, Europe, Africa and the Middle East; he is currently professor of History at the University of Nantes and member of the Academia Europæa and the Reial Acadèmia de Bones Lletres de Barcelona. He has received numerous prizes and distinctions, including two major grants from the European Research Council and the Prix Diane Potier-Boès from the Académie Française (2008). He is author of numerous articles and books, including Petrus Alfonsi and his Medieval Readers (1993) Saracens: Islam in the Medieval European Imagination (2002), Sons of Ishmael (2008), Saint Francis and the Sultan (2009), Faces of Muhammad: Western Perceptions of the Prophet of Islam from the Middle Ages to Today (2019), and Nouvelle histoire de l’islam, VIIe-XXIe siècles (2022). He is one of the four coordinators of the European Research Council program “The European Qur’ān” (2019-2025; euqu.eu).