Guest Blog by Princeton's Ofir Haim: A Jewish Real-estate Tycoon in Bamiyan?

A Jewish Real-estate Tycoon in Bamiyan?

Ofir Haim, 2 February 2022

How does one become a real-estate tycoon in pre-Mongol Afghanistan? Perhaps we could have known the answer if we had spoken to Yehuda ben Daniel, a Jewish landowner from eleventh-century Bamiyan. Many documents from Yehuda’s archive survived today and are part of the rich corpus dubbed New Manuscripts from Afghanistan (NMA), also known as the “Afghan Genizah.”

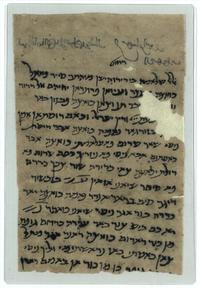

The archive documents elucidate interreligious relations in the pre-Mongol Iranian world from a unique viewpoint: A Jewish landowner and his dealings with the rural population. Since the beginning of the eleventh century, the archive documents tell us, Yehuda ben Daniel purchased plots of land in rural settlements, particularly those located in the Bamiyan valley. In some cases, the land was bought by one of his agents, as shown in a Judeo-Persian letter from the National Library of Israel (Ms. Heb. 8333.4=4). The letter concerns a monetary dispute between the sender, “Mūsā b. Isḥāq the Jew,” and a man named Nissi. The disagreement may have emerged after Mūsā had purchased the land on Yehuda’s behalf.

[image of NLI, Ms. Heb. 8333.4=4_r; Courtesy of the National Library of Israel]

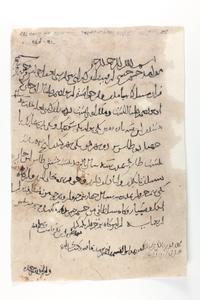

What did Yehuda do with his landed property? To answer this, we resort to yet another text housed at the National Library of Israel (Ms. Heb. 8333.15=4). This document is drawn up in the form of an acknowledgment (iqrār) by Ḥusayn b. Ḥasan concerning the lease of three plots of land in the village of Rām K.Ray/K.Rī(?). The toponym Rām K.Ray/K.rī (in Hebrew script: ראם כרי) appears quite often in Yehuda ben Daniel’s account books, demonstrating his strong ties to the inhabitants of this village. Significantly, the names of the three parcels of land appear in Yehuda’s crop revenue report from his landed property. The report refers to the month of Marcheshvan in the year 1337 of the Seleucid era (=1026 CE). In other words, Yehuda was active in this village for at least thirteen years before drawing up the discussed legal document.

[image of NLI, Ms. Heb. 8333.4=15_r; Courtesy of the National Library of Israel]

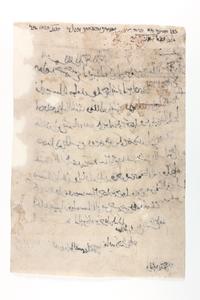

Another interesting detail about this document is a short archival note written in Judeo-Persian at the top part of verso. The note contains the main details of the legal transaction, namely the names of the lessee and the plots of land, the amount of grain given together with the land, and the year according to the Seleucid Era (1350, corresponding to 1039 CE).

A close inspection of the document reveals another exciting detail about the document. Although it has undergone a conservation process, some horizontal folding signs are still apparent. These signs suggest that Yehuda ben Daniel folded the document into a narrow rectangle containing the Judeo-Persian note, thus enabling easier identification of the folded documents by the archive owner.

[image of NLI, Ms. Heb. 8333.4=15_v; Courtesy of the National Library of Israel]

How did Yehuda ben Daniel manage to transport his share of the crops from the countryside to his hometown (or market)? What did he do with all the wheat, barley and legumes? And where can we find the Ghaznavid state in all of this? Questions such as these are part of my research on the Yehuda ben Daniel archive. It involves a meticulous study of documents, mainly letters, legal texts and account books, written in New Persian in both Arabic and Hebrew script. Through close reading and analysis of these documents, I hope to shed new light on the social fabric of the early Ghaznavid state (977-1186 CE) through the eyes of its Jewish minority.

Ofir Haim is a Fellow of the Mandel Scholion Research Center