Document of the Month 5/25: A Versatile Amulet

Doctors Hate Him. Scribe Cures Back Pain In One Simple Mindblowing Trick

by Sarah Kiyanrad

The desire for health has united us humans throughout history. Back pain, for example, is not an invention of homo computerus − apparently, many of our ancestors were already groaning and putting their hands on the small of their backs. While we rely on advanced medicine for curing aches and pains, historically empirical medical knowledge was in competition with a religious understanding of the body. Amulets offer a fascinating lens through which to reflect on the often not very romantic relationship between medicine and religion (leaving aside the equally interesting question of He-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named − Lord Magic). In the following, we look at a Persian-Arabic amulet that appears to be almost a thousand years old: it was intended to help against numerous ailments and afflictions that life still plagues us with today. We do not know how the wearer of this amulet felt about medicine, let alone its scribe. Did he have no access to medical treatment and could only hope for divine help? Or, quite the opposite, did he trust in God and held medicine in low regard? Was he open to both, a pragmatist who took what he could get? Did he view the amulet as medicine? Or had he been given the amulet as a wedding present and had to be seen with it from time to time out of respect for his aunt? Whatever the case, the amulet discussed here survived for many hundreds of years, and even if completely ineffective against back pain, it holds a powerful charm − like all objects that connect us with the distant past.

Scrolling fortune

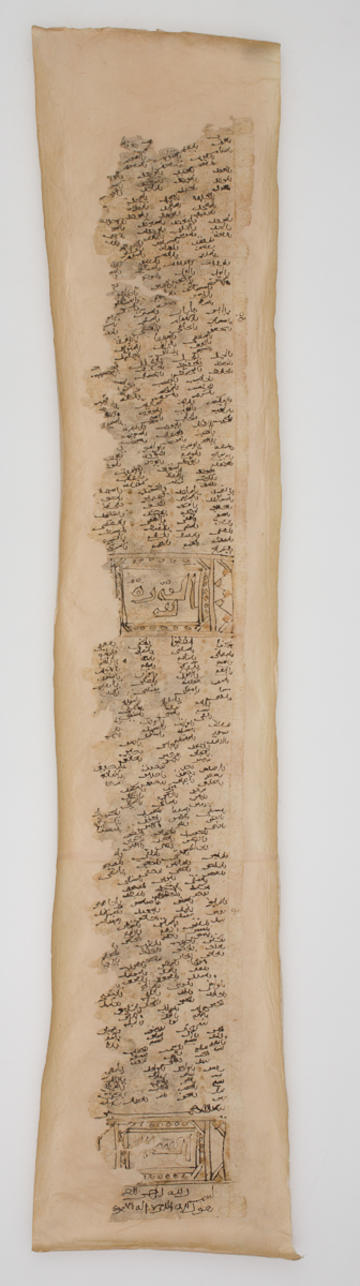

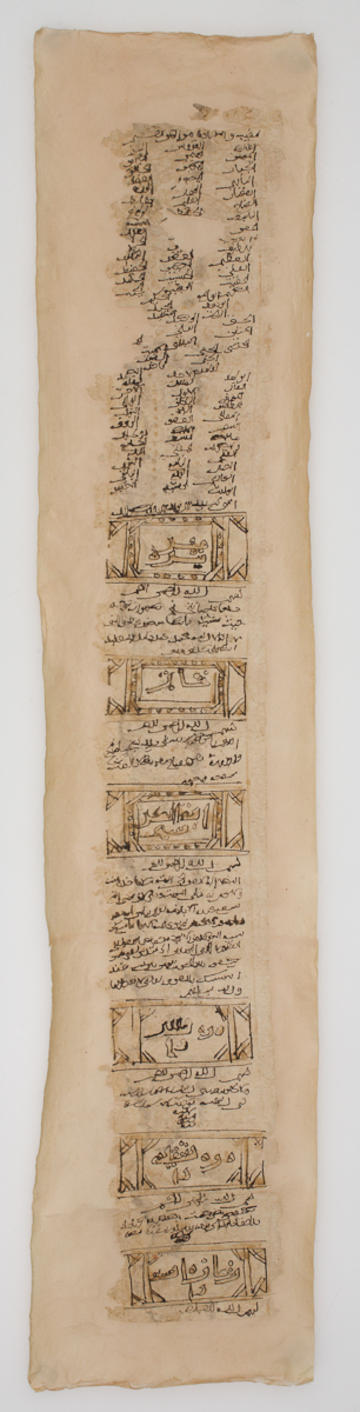

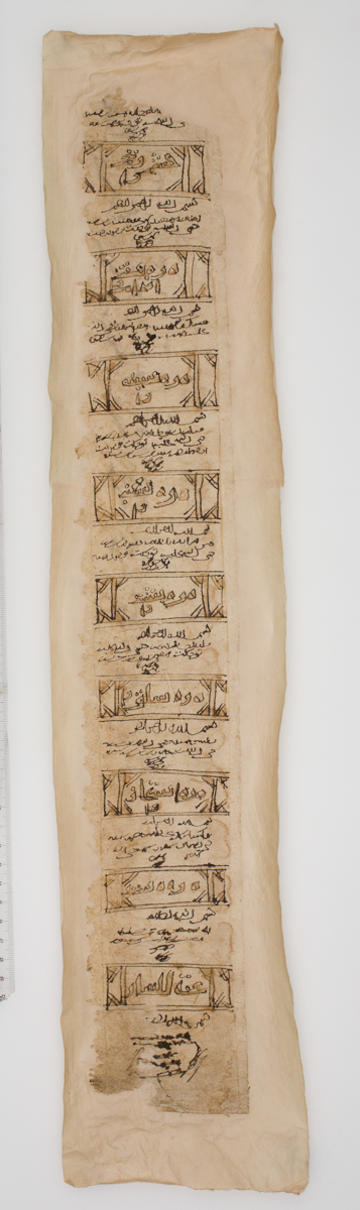

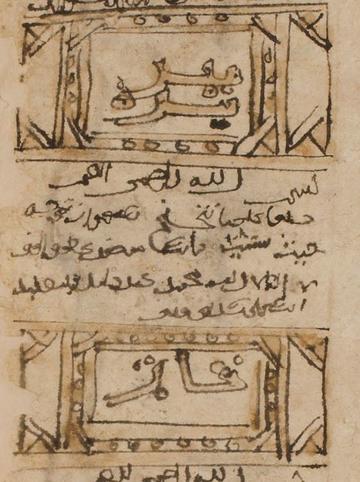

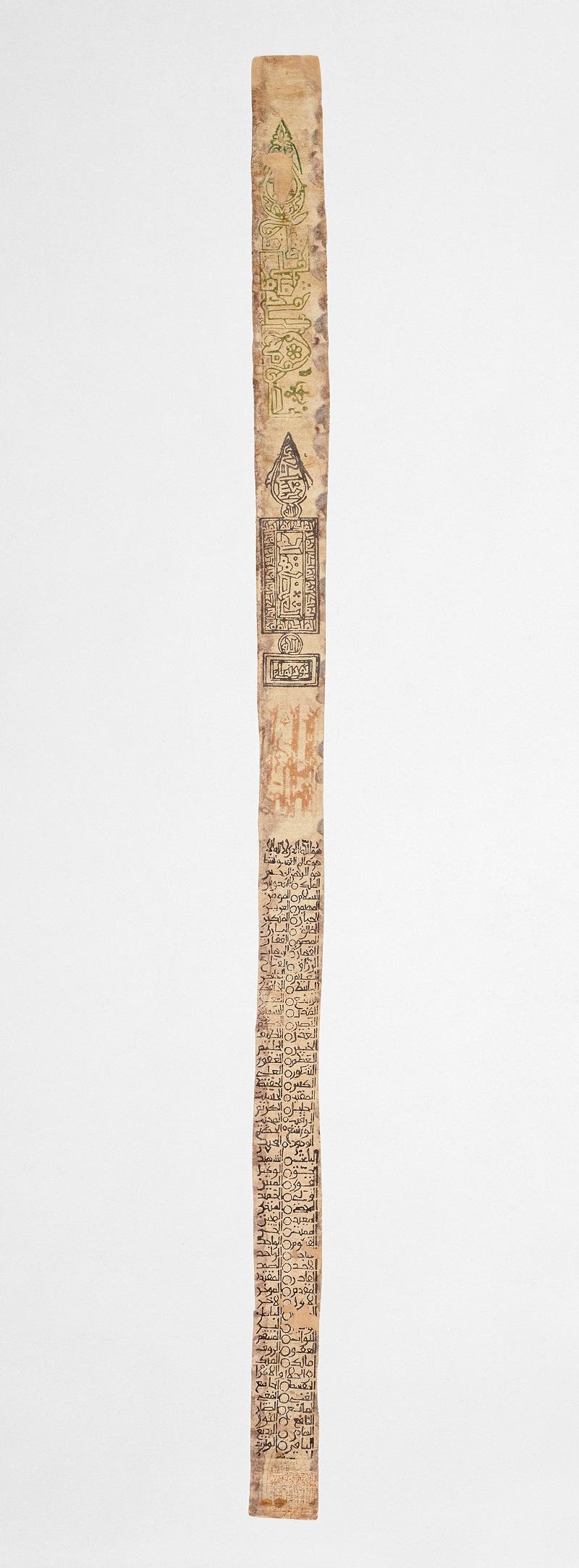

Our amulet was found amongst the papers that Prof. Sir Nasser D. Khalili purchased from Afghanistan, and it probably dates from the 11th or the 12th century. It is a kind of textual triptych or trilogy: the amulet consists of three unconnected paper scrolls that unroll downwards. The technical term for such vertical scrolls is rotuli (singular: rotulus). The scrolls have roughly the same shape, each measuring approximately 10 cm wide over 58 cm high (see Figures 1, 2, 3) and are inscribed on one side. Although physically separate, perhaps for purely practical reasons, the scrolls belong together and are textually connected. The order suggested by Arezou Azad and her team, who have prepared their edition and translation, is Khalili 53, Khalili 54, Khalili 52.

Fig. 1: The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, Khalili 53, undated, Afghanistan. Courtesy of the Nasser D. Khalili Collection.

Fig. 2: The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, Khalili 54, undated, Afghanistan. Courtesy of the Nasser D. Khalili Collection.

Fig 3: The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, Khalili 52, undated, Afghanistan. Courtesy of the Nasser D. Khalili Collection.

Had the three parts been physically joined together, the amulet would have been 174 cm long−about as tall as a human being! At first glance, this length may seem surprising. It does not seem particularly practical, as an amulet was something you carried with you. In fact, amulet scrolls many meters long were quite common in the cultural context we are dealing with here; rolled tightly, people wore them around the neck or the upper arm in cylindrical containers.

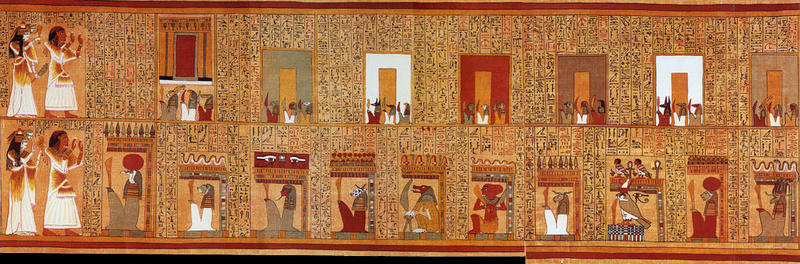

Today we are used to our typical book format, the codex. But scrolls are (again/still) part of our everyday lives: when we browse websites, read a Word document or a multi-page PDF file, we return to good old scrolling. For a long time, the scroll was a common writing medium. Astonishing examples have been preserved from Pharaonic and Roman Egypt (the Papyrus of Ani, over 20 meters long, is particularly impressive, see Figure 4). Torah scrolls are another example that many of you will be familiar with.

Fig. 4: Papyrus of Ani (detail), circa 1250 BCE, Thebes. British Museum, museum number EA10470. Facsimiles produced by E. A. Wallis Budge. Wikimedia, public domain.

In the Arabic-speaking context, famous amulet scrolls date from around 900 to 1400 CE (Figure 5). It is assumed that most of them originate from Egypt, perhaps because of the long and well-known tradition of scrolls there, but Iraqi and Syrian amulets have also been identified. Moreover, evidence from literary sources, together with the known specimens − including ours − shows that amulet scrolls were also produced and used in this period in Persian-speaking milieux (see more on this below).

Fig. 5: Talismanic Scroll, 11th century, Egypt. Metropolitan Museum of Art, object number 1978.546.34. Gift of Nelly, Violet and Elie Abemayor, in memory of Michel Abemayor, 1978. Public domain.

Arabic scrolls from the period between 900 and 1400 CE are usually printed with woodblocks and are thus known as block prints (Arabic ṭarsh). In contrast, the three-part Khalili amulet is handwritten. Although a handwritten amulet must have been more expensive than a printed one, our scribe did not make any special effort. The writing seems hastily executed (perhaps an attribute of ‘doctors’ already then?) and in some places there are mistakes. Alternatively, the hasty writing style could be a sign of a skilled scribe who knew how to produce or copy large quantities of text quickly. Since the headings seem to have been done in a similarly hasty manner, our scribe probably executed them as well. This tells us nothing about the language(s) in which he usually communicated, but at least we know that he was practised in writing texts in Persian and Arabic. Not all words could be read so far − perhaps they simply should not be read, because the alienation of writing, including the use of alien scripts and languages, is a genuine part of amulet culture.

Apart from some faded red embellishments (such as circles) on Khalili 53, the amulet is monochrome, black ink on paper. This reinforces the impression of a simple production and resembles printed amulets. The three scrolls are largely undecorated and are ‘effective’ through their words alone. A number of words, as well as the amulet’s functions given in Persian are visually emphasized and framed. The decoration in the first five frames of the amulet is slightly more elaborate, with additional circular shapes (see Figure 6). Although the Khalili amulet was made only a few centuries after the Arab invasion, it bears no trace of the rich and diverse Sasanian amulet culture (including metal scrolls).

The body's grimaces

Amulets are intended to either change the current state of things or preserve it for the future. One of the most important fields of application for amulets is disease and disease prevention. This is exactly what our amulet is about. It begins with an invocation to God and a depiction of His strength and greatness, followed by a part that tells us more about the use of the amulet.

Khalili 54 and Khalili 52 contain Persian names of various diseases and ailments that the amulet was designed to heal or prevent: from headaches and the dreaded evil eye to shoulder, back, leg, bone, and hand pain. They are written in a Kufiesque script and enclosed in rectangles. Two further protective functions precede them. The first of these is muhra-yi tīr, a protection against arrow shots and wounds of all kinds. The second appears to read khātam, seal (Figure 6). Khātam − like muhra − was one of various words denoting an amulet. While the reading of the word on our object is uncertain, some block-printed amulets refer to themselves as khātam. Moreover, khātam evokes a strong association with the famous seal of Solomon, a protective, power-conferring device that prominently appears as a hexagram on amulets. Our amulet was therefore not intended to protect against a particular kind of harm but was an all-rounder. It could be worn preventively to ward off the listed evils, but it could also be used to heal existing ailments.

Fig. 6: The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, Khalili 54, undated, Afghanistan (detail). Courtesy of the Nasser D. Khalili Collection.

Unfortunately, we do not know who the amulet belonged to. Our scribe − based on the evidence of other amulets most probably a man − also remains anonymous. Unlike many later amulet scrolls, the Khalili amulet does not mention any names and is undated. This is not surprising and may hint at the influence of the contemporary practice of amulet printing. But it may also mean that the amulet was not custom-made for a specific person. In contrast, the Jewish Aramaic amulet from Bamiyan, produced around 1000 CE, bears the Persian name of its female wearer, a woman named Mahnāz, daughter of Kadbānū (edited by Shaul Shaked in Shaked 2009). We know that there were professional amulet producers, but also occasional writers. It is easy to imagine that they composed amulets of varying complexity and individualization, including ready-made ‘off-the-shelf’ amulets.

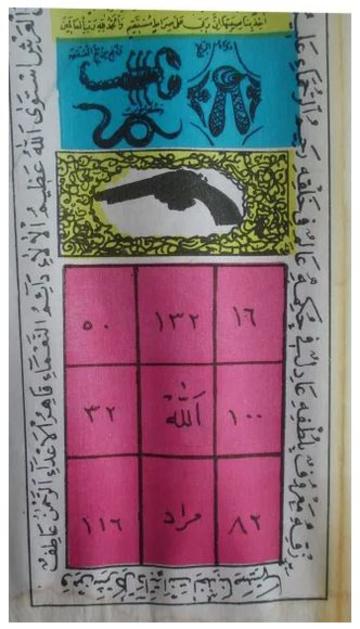

We can tell that our amulet was probably used and produced in a Persian-speaking milieu, which is also suggested by the context in which the documents were purchased. The framed headings or fields of application, i.e. diseases and evils, are in Persian. They can therefore be seen as a bit of a ‘medication leaflet’ that explains what each section of the amulet is meant to protect against or heal. One of these headings could indicate a more specific context in which the amulet was used. The very first category, the aforementioned muhra-yi tīr, protection against arrow shots and wounds of all kinds, points to a military context. And indeed, amulets were particularly needed and often used in battle. We know of amulet types specially made for war, but also of amulet scrolls richly illustrated with weapons of war against which they were intended to protect (including swords, and, in more recent centuries, also guns, Figure 7). However, as protection from arrows is ultimately just one among many more everyday applications mentioned on the Khalili amulet, we should not over-interpret this.

Fig. 7: Amulet scroll, 19th century, Ottoman lands (detail). Halûk Perk Collection. Photograph: Christiane Gruber. Courtesy of Christiane Gruber. Originally published as Figures 4 and 5 in Christiane Gruber, “The Arts of Protection and Healing in Islam: Amulets and the Body”, Ajam Media Collective Blog, April 30, 2021 (accessed 22 April 2025).

The way words work

Unlike the captions, the body of the text supposed to ward off the respective illnesses or evils is in Arabic. This combination of Persian ‘instructions’ or headings and Arabic main text is also known from other amulets of the time, for example from a scroll in the David Collection (which is, however, printed) (see Figure 8). It points to a Persian, Islamicate milieu.

Fig. 8: Amulet scroll with polychrome block print, 10th-11th century, Egypt, or perhaps Iran. David Collection, Inventory number 85/2003. Photograph: Pernille Klemp. Courtesy of the David Collection.

The Arabic text of our three scrolls consists of religious content throughout. Schematically, the structure can be represented as follows:

- Introduction: invocations to God, the 99 names of God (Khalili 53 and 54);

- Transition: an invocation against arrow shots and the khātam (Solomonic seal?), the Throne verse Q. 2:255, and Q. 2:256 (Khalili 54);

- Main part: diseases and evils, with the counteracting verse Q. 9:129 (Khalili 54 and 52).

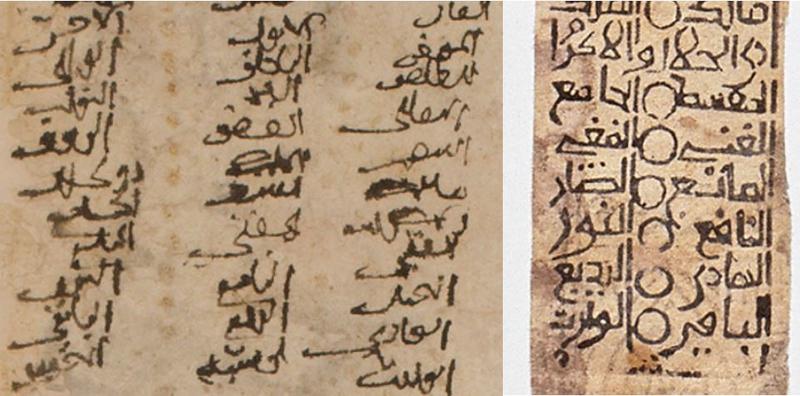

These elements are quite typical of amulets from Islamicate environments. The 99 names of God take up a large part of the amulet scroll from the David Collection shown in Figure 8. As on our amulet, the names are visually separated from each other by circles (arranged there in two columns, and on our amulet mostly in three; Figure 9). This division of the one power into many different aspects made it possible to counter the multitude of threats with a multitude of characteristics despite monotheistic thinking.

Fig 9: Amulet scroll, the Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, Khalili 54 (left) and David Collection, Inventory number 85/2003 (right) (details). Courtesy of the Nasser D. Khalili Collection and the David Collection.

The Qur’anic verses used in the Khalili amulet are Q. 2:255−256, 59:22, and 9:129. The divine power expressed in them was particularly important to producers and owners of amulets. Although entire manuals exist that emphasize the specific effects of certain verses, producers were obviously often pragmatic and used the verses they knew. However, some verses and chapters were used preferentially. One of these is the Throne verse Q. 2:255 (in Arthur Arberry’s translation: “God there is no god but He, the Living, the Everlasting. Slumber seizes Him not, neither sleep; to Him belongs all that is in the heavens and the earth. Who is there that shall intercede with Him save by His leave? He knows what lies before them and what is after them, and they comprehend not anything of His knowledge save such as He wills. His throne comprises the heavens and earth; the preserving of them oppresses Him not; He is the All-high, the All-glorious”). It is documented on numerous amulets and amulet cases throughout the centuries. For example, it appears on a silver amulet case from the late 18th- or early 19th-century Iran, preserved in the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery of the Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art.

Interestingly, the following verse, Q. 2:256, is also quoted on Khalili 54, which lists attributes of God, but is mainly known for its beginning: “No compulsion is there in religion. Rectitude has become clear from error. So whosoever disbelieves in idols and believes in God, has laid hold of the most firm handle, unbreaking; God is All-hearing, All-knowing” (translation by A. Arberry). The throne topos is taken up in Q. 9:129 and creates a contextual link between the quotations (A. Arberry: “So if they turn their backs, say: ‘God is enough for me. There is no god but He. In Him I have put my trust. He is the Lord of the Mighty Throne’”). A fragmentary block print amulet from Egypt, dating between 900 and 1400 CE, consists of some elements that we know from our amulet, namely invocations to God and verse Q. 9:129 (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, P.Vindob. A. Ch. 12136; edited and translated by Schaefer 2006, 118−121). Although this verse is not frequently used on amulets, it is often visually highlighted when it appears, perhaps because it is the last verse of its chapter. One example is an amulet scroll written by a certain Muḥammad b. Muḥammad b. al-Bayṭār al-Shāfiʿī in the 14th century (more precisely, in Rabīʿ I 775/August or September 1373). It is kept in Berlin (Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, Ms. or. oct. 218) and has been examined in detail by Tobias Nünlist (Nünlist 2018, 180−196). Chapter 9 is reproduced there in its entirety, with its final verse (which appears on our amulet) highlighted in red (Nünlist 2018, 184).

The text of our amulet ends rather abruptly on Khalili 52 with a heading for the last woe: tongue tie. Usually, we would expect a concluding formula, an ending that closes the amulet. Perhaps it was omitted from the amulet, or perhaps we are missing another scroll (or other scrolls) of the amulet. This would not be entirely inconsistent in terms of content, as tongue tie could possibly open up a new category of application fields. Tongue tie refers to a defensive measure: one’s own tongue or one’s self has come under the control of another person and should be released from it. Or else... it is not entirely impossible that the tongue of another person is being symbolically tied here, and the wearer wants to bring it under their control.

It is not unusual for an amulet to combine several different functions. Some span a spectrum from luck in gambling to earache. Who knows what else our amulet was trying to protect against. And − is it merely a coincidence that three scrolls with relatively harmless purposes have been preserved here? Amulet-making manuals do describe amulets intended to inflict harm, but hardly any such examples have survived.

Once more: back pain

One of the great miracles performed by amulets from the past is that they bring us closer to the people of the past in a way entirely unlike other documents, such as official decrees. We imagine the stressed (or bored, or shady, or poorly paid) scribe, and his customer, desperately looking for a cure for their back pain. They are incredibly distant from us: we may even smile at them a little for their belief in amulets. We feel sorry for them, because today there are so many wonderful medical possibilities for the ailments they fear. At the same time, we are very close to them − we know the pain that plagues them. We know it so well. We do our yoga. We go to the doctor. We take a painkiller. And if no one is looking or listening (and only then), we might ask for a few globules at the pharmacy.

The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, Khalili 52. Unpublished transcription and translation by N. Saqee, E. Shawe-Taylor, M.M. Arghandehpour, and A. Azad

1. [ -/+ 6]

2. [حسـ]بی الله علیه توکلت و هو رب

3. العرش [؟]

4. العظیم [؟]

5. چشم زخم

6. را

7. بسم الله الرحمن الرحیم

8. [ -/+ 6]

9. حسبی الله علیه توکلت و هو رب

10. العرش [؟]

11. العظیم [؟]

12. درد هفت

13. اندام را

14. بسم الله الرحمن الرحیم

15. [-/+ 6] حسبی الله

16.علیه توکلت و هو رب

17. العرش [؟]

18. العظیم [؟]

19. درد سینه

20. را

21. بسم الله الرحمن الرحیم

22. [-/+ 8]

23. حسبی الله علیه توکلت و هو رب

24. [-/+ 8]

25 . العرش [؟]

26. العظیم [؟]

27. درد شانه [؟]

28. را

29. بسم الله الرحمن الرحیم

30. [-/+7]

31. حسبی الله علیه توکلت [ -/+ 3]

32 . العرش [؟]

33. العظیم [؟]

34. درد پشت

35. را

36. بسم الله الرحمن الرحیم

37. [ -/+3] حسبی الله علیه

38. توکلت و هو رب

39 . العرش [؟]

40. العظیم [؟]

41. درد ساق را

42. بسم الله الرحمن الرحیم

43. [-/+ 9]

44. حسبی الله علیه توکلت و هو رب

45. العرش [؟]

46. العظیم [؟]

47. درد استخان

48. را

49. بسم الله الرحمن الرحیم

50. [-/+ 9]

51. حسبی الله و هو رب حسبی الله

52. [ -/+ 1] العرش [؟]

53. العظیم [؟]

54. درد دست را

55. بسم الله الرحمن الرحیم

56. [-/+ 8]

57. [-/+ 4]

58. العرش [؟]

59. العظیم [؟]

60. عقدة اللسان

61. بسم الله الرحمن الرحیم

62. [-/+ ؟]

63. [-/+ ؟]

64. [-/+؟]

65. [-/+ ؟]

66. [-/+ ؟]

The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, Khalili 52. Unpublished transcription and translation by N. Saqee, E. Shawe-Taylor, M.M. Arghandehpour, and A. Azad

1. [ -/+ 6]

2. I put my trust in Him – He is the lord

3. of the mighty

4. throne.

5.-6. The Evil Eye

7. In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate

8. [+/- 7]

9. I put my trust in Him – He is the lord

10. of the mighty

11. throne.

12.-13. Body pain

14. In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate

15. [+/- 6] I put my

16. trust in Him – He is the lord

17. of the mighty

18. throne.

19.-20. Chest pain

21. In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate

22. [-/+ 8]

23. I put my trust in Him – He is the lord

24. [-/+ 8]

25. of the mighty

26. throne.

27.-28. Shoulder pain

29. In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate

30. [-/+7]

31. I put my trust in Him [+/-3]

32. of the mighty

33. throne.

34.-35. Back ache

36. In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate

37. [ -/+3] I put my

38. trust in Him – He is the lord

39. of the mighty

40. throne.

41. Lower leg pain

42. In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate

43. [-/+ 9]

44. I put my trust in Him – He is the lord

45. of the mighty

46. throne.

47.-48. Bone pain

49. In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate

50. [+/- 9]

51. I put [my trust] in Him - He is the lord I [put my trust] in Him

52. [+/- 1] of the mighty

53. throne.

54. Hand pain

55. In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate

56. [-/+ 8]

57. [-/+ 4]

58. of the mighty

59. throne.

60. Tongue tie

61. In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate

62. [-/+ ?]

63. [-/+ ?]

64. [-/+ ?]

65. [-/+ ?]

66. [-/+ ?]

Arberry, Arthur John. The Koran Interpreted. New York: Collier, 1980.

Bulliet, Richard W. “Medieval Arabic Ṭarsh: A Forgotten Chapter in the History of Arabic Printing”. Journal of the American Oriental Society 107 (1987), 427–438.

Canaan, Tewfik. “The Decipherment of Arabic Talismans”. Berytus 4 and 5 (1937 and 1938), 69–110 and 141–151.

Gruber, Christiane. “The Arts of Protection and Healing in Islam: Amulets and the Body”. Ajam Media Collective Blog, April 30, 2021 (accessed 22 April 2025).

Kiyanrad, Sarah. “Sasanian Amulet Practices and Their Survival in Islamic Iran and Beyond”. Der Islam 95/1 (2018), 65–90.

Nünlist, Tobias. Schutz und Andacht im Islam. Dokumente in Rollenform aus dem 14.–19. Jh. Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2020.

Nünlist, Tobias. "Entzauberte Amulettrollen. Hinweise zu einer typologischen Gliederung". In Die Geheimnisse der oberen und der unteren Welt. Magie im Islam zwischen Glaube und Wissenschaft, edited by Sebastian Günther and Dorothee Pielow (eds). Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2018, 247–293.

Garcia Probert, Marcela A. and Petra M. Sijpesteijn (eds). Amulets and Talismans of the Middle East and North Africa in Context. Transmission, Efficacy and Collections. Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2022.

Saif, Liana et al. (eds). Islamicate Occult Sciences in Theory and Practice. Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2020.

Schaefer, Karl. Enigmatic Charms. Medieval Arabic Block Printed Amulets in American and European Libraries and Museums. Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2006.

Savage-Smith, Emilie. “Amulets and Related Talismanic Objects”. In Francis Maddison and Emilie Savage-Smith, Science, Tools, and Magic, Part 1: Body and Spirit, Mapping the Universe. London et al.: The Nour Foundation et al., 1997, 132−147.

Shaked, Shaul. “A Jewish Aramaic Amulet from Afghanistan”. In With Wisdom as a Robe – Qumran and Jewish Studies in Honour of Ida Fröhlich, edited by Károly Dániel Dobos and Miklós Kőszeghy. Sheffield: Phoenix Press, 2009, 485–494.

Cite this article

Kiyanrad, S. 2025. “Doctors Hate Him. Scribe Cures Back Pain in One Simple Mindblowing Trick.” Document of the Month. Invisible East. doi: 10.5287/ora-aoqj7gzay.

About the author

Sarah Kiyanrad is interested in the cultural history of Iran in the long term, from amulets to verse chronicles. At present she is a research associate at LMU Munich.

The online series, Document of the Month, presents some of the most interesting and revealing medieval documents from the desks of Invisible East researchers and their colleagues worldwide. Each piece in the series is dedicated to a single document or a closely related group of documents from the Islamicate East and tells their story in an engaging and accessible way. You will also find images, editions and translations of the documents. If you would like to contribute to the Document of the Month series, please, get in touch with Nadia Vidro.