Document of the Month 1/25: An Early Calligraphic Signature

Nishān, ʿAlāma, or Ṭughrā :

A Case Study from the Firuzkuh papers

by Edward Shawe-Taylor

How often do you have to sign your name to something? Whether it’s a contract, a form, or even a colleague’s farewell card, adding your signature is such a mundane act that we rarely consider its purpose or value. Now imagine that each time you signed something, you had to create a large, elaborate signature as intricate and precise as a great work of art. This month’s Document of the Month may contain the earliest known example of one of history’s most elaborate forms of signage: the ṭughrā.

The Firuzkuh papers and the Dīwān al-Ikhtiyārī

The document, Firuzkuh 28, is part of a cache of paper documents from medieval Afghanistan. These were discovered by treasure-hunters in the village of Shahr-e Khuru, located in the Ghalmin province of Ghur. While searching for gold in the nearby Kamara cliffs, they stumbled upon a cave containing 101 paper documents. The documents were later sold to Mirza Khwāja Muḥammad, a government official in Ghalmin, who pasted them into his personal notebook. In 2009, Khwāja Muḥammad published a monograph on the documents with the assistance of Nabi Saqee, now a key member of the Invisible East team. In 2020, the documents were donated to the Afghanistan National Archives, where they remain today. You can read more about the Firuzkuh papers in a blog by Nabi Saqee.

Fig. 1: Kamara Cliffs, from “Striking Gold: The Discovery of Medieval documents from Afghanistan”, a documentary produced by the Invisible East

Firuzkuh 28 is one of a number of documents in this corpus produced by the same office: al-Dīwān al-Ikhtiyārī. The documents are dated between 1217-1220 CE, the period immediately after the last Ghurid ruler was overthrown by the Khwārazmshāhs. No sources from any part of the Islamic world mention an office by this name, so it is most likely that the office was named after the senior official in charge of administering this specific region, who must have had the laqab (a type of honorific title) “Ikhtiyār al-Dīn” (the Choice of the Faith).

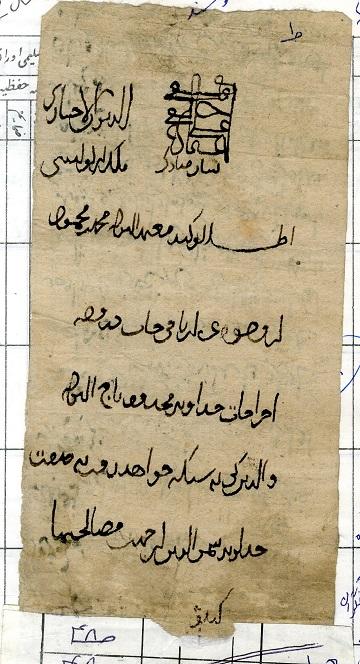

The document contains an order to a certain Muḥammad b. Maḥmūd asking him to move some of the money that the office received from the tithe (ʿushr) tax and pay it to the lord Tāj al-Dawla to cover his travel expenses. The lower half of the document is missing.

Fig. 2: Firuzkuh 28 (image courtesy of Nabi Saqee). Full details of the document, including a transcription and English translation can be found in the Invisible East Digital Corpus

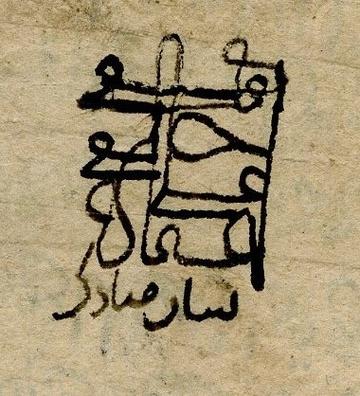

The document follows a similar layout to others in the corpus. The title of the office, al-Dīwān al-Ikhtiyārī, is written in the top left-hand corner, with the name of an official written beneath. The two-part name is hard to decipher, but the first word appears to be “Malik”. In the middle of the page, above the first line of the main text there is a feature that is unique in the corpus: an elaborate calligraphic signature, in which Arabic letters overlap to form a sort of square seal. Beneath is written, “the blessed sign” (nishān mubārak).

Fig. 3: Detail of Firuzkuh 28, showing a calligraphic signature at the top of the document (image courtesy of Nabi Saqee)

A calligraphic signature

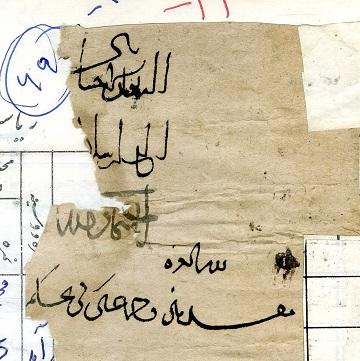

To interpret the signature in Firuzkuh 28, we can compare its positioning to other documents in the corpus. For instance, Firuzkuh 47 features a similar layout, with the office name in the top left and the name of an official (“Ulugh Arsalān”) below. However, in the same central position occupied by the signature, Firuzkuh 47 contains the Arabic phrase “Glory be to God” (li-llāh al-ʿizza).

Fig. 4: Detail of Firuzkuh 47, showing the office name and the name of an official in the top left and the pious phrase “Glory be to God” (li-llāh al-ʿizza) in the centre, above the first line of the main text (image courtesy of Nabi Saqee)

Pious phrases such as these are common in chancery documents from across the Islamic world. They are known as ʿalāʾim (sing. ʿalāma) and they served as signatures for rulers and government officials. While official documents may be written by scribes, the ʿalāma was required, at least ostensibly, to be written by the ruler or minister himself. The overlapping Arabic letters in the Firuzkuh 28 signature make it difficult to decipher, but the words iʿtimād and ʿalā are discernible at the base (the signature is to be read from the bottom up). Researchers in the Invisible East team have initially suggested that the reading begins with, “reliance upon Muḥammad the seal of…” of which phrase, one of the most common conclusions is “the prophets” (iʿtimād ʿalā Muḥammad khātim al-anbiyāʾ). However, after this article was published online, Boris Liebrenz of the Saxon Academy of Sciences and Humanities in Leipzig, got in touch with a suggested revision of the reading: “my reliance is upon my creator, and this suffices” (iʿtimādī ʿalā khāliqī wa-kafā). We are grateful to Boris for this correction. It is interesting that the ruling Khwārazmshāh at this date, ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn Muḥammad had a similar ʿalāma: “My trust is in God alone” (iʿtimādī ʿalā Allāh waḥdahu). Perhaps the official who drafted this document chose an ʿalāma for himself that was similar to that of the ruler. It is interesting to note that this sign is labelled in Firuzkuh 28 not as an ʿalāma, but as a “nishān.” This Persian word meaning “mark” or “signet” is not found in the sources which discuss Persian chancery practices, but its meaning mirrors exactly the meaning of the Arabic word ʿalāma. Perhaps “nishān” is simply a Persian calque of this technical Arabic term.

An early form of the ṭughrā ?

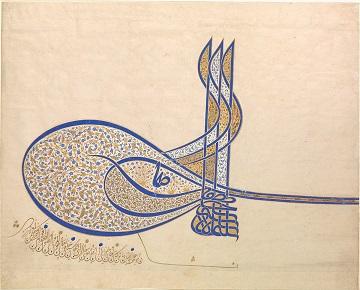

Syntactically, our signature appears to have served the same bureaucratic function as the Arabic ʿalāma. However, visually, it represents something very different. Students of Ottoman or late Mamluk history will be familiar with the placement and visual style of such a symbol. The earliest surviving documents from the Ottoman chancery, dating from the reign of Orhan (r. 1323/4–1362), exhibit similar signatures, positioned centrally above the opening line of the document. However, unlike the Arabic ʿalāma, which contained a pious phrase, these signatures – known as ṭughrās – contained the sultan’s name, their patronymic, and, in later examples, honorific epithets.

Over time, the Ottoman ṭughrā evolved into an increasingly elaborate emblem, until, by the reign of Süleiman the Magnificent (r.1520-1566), it had become an ornate work of art in and of itself, showcasing the mastery of the Ottoman court’s calligraphers and illuminators.

Fig. 5: Ṭughrā of Sultan Süleiman the Magnificent (r. 1520–66). The Met, New York, Rogers Fund, 1938 (38.149.1) (image in public domain)

The origins of the ṭughrā, however, lie in a much earlier period of Islamic history. Its roots can be traced back to the Seljuqs, a Turco-Persian dynasty that dominated the eastern Islamic world from the 11th to the 13th centuries. Both the Ghurids and the Khwārazmshāhīs began their political careers as Seljuq vassals, and it is fair to assume that Seljuq bureaucratic traditions deeply influenced their practices. The Seljuqs were the first to incorporate a Turkic tribal mark known as the tamgha into their signage. This pictorial mark, a round-headed staff beside an arch shape, appears in the coinage of the Seljuqs.

Fig. 6: Gold dinar of the founder of the Great Seljuq Empire Tughril Beg (Rayy, 440 AH / 1048–1049 AD), showing the round-headed staff beside an arch shape tribal mark. American Numismatic Society 1922.211.126. ©2024 American Numismatic Society (Public Domain Mark). https://numismatics.org/collection/1922.211.126

With no chancery documents surviving from the early Seljuq period, all our information about the nature of the ṭughrā comes from literary sources. Some of these sources describe the tribal mark being combined with the names and titles of the ruler – in a manner similar to the Ottoman ṭughrā. Other sources, however, suggest that the tamgha (a tribal mark) was incorporated with the ʿalāma (a pious phrase) in the signage of documents. One 12th-century source, Mujmal al-Tawārīkh, even applies the name ṭughrā directly to this pious phrase.

Could this alternative form of the ṭughrā explain the signature in Firuzkuh 28? It would come as no surprise that the Ghurids and Khwārazmshāhs emulated the administrative norms of their former rulers, the Seljuqs. Indeed, the influence of the Seljuq chancery was far-reaching, stretching as far as Ayyubid Egypt. As previously mentioned, the Khwārazmshāh ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn Muḥammad used an ʿalāma with similar wording to Firuzkuh 28. Unfortunately, no documents bearing the signatures of the Khwārazmshāh rulers have survived. Al-Nasawī (d. 1250), secretary to ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn’s son, recorded that ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn had a stamp made of his ʿalāma, enabling his daughter to sign documents on his behalf. This account implies that the ʿalāma already exhibited a degree of graphic ornamentation, akin to the visual sophistication seen in later ṭughrās. We see something of this complexity in the ʿalāma of Firuzkuh 28. The provincial official who signed the document appears to have adopted an ʿalāma that followed a similar syntactic format and, more significantly, executed it in the same grand monographic style employed by the Seljuq and Khwārazmshāhī ruling elite. With its graphic, square layout, it is easy to imagine the design being reproduced as a stamp.

Conclusion

Firuzkuh 28 was certainly not issued by the highest echelons of the Khwārazmshāhī bureaucracy. The document originated from al-Dīwān al-Ikhtiyārī, a provincial office tasked with overseeing the taxation of a relatively small region ruled by the Firuzkuh branch of the Ghurid confederation and its Khwārazmshāhī heirs. Nevertheless, the visual impact of its signature demonstrates how the bureaucratic practices of the Khwārazmshāhs, and, by extension, the Seljuqs permeated even local levels of administration. The incorporation of such a signature would have lent the document an aura of authority and gravitas, mirroring the stylistic conventions of the loftier bureaus that issued documents on behalf of the ruling elite. While many of the chancery practices of the Seljuqs and their successors remain known to us only through literary sources, this modest, fragmentary document may preserve the earliest known example of a calligraphic motif that would later evolve into one of Islam’s most iconic bureaucratic symbols: the ṭughrā.

Aubin, Jean, and S. M. Stern. Documents from Islamic Chanceries. First Series. Oxford: Cassirer, 1965.

Azad, Arezou, and Pejman Firoozbakhsh. " ‘No One Can Give You Protection’ The Reversal of Protection in a Persian Decree Dated 562/1167." Annales islamologiques 54 (2021), 125-138.

Husseini, Said Reza. "The Muqaddam Represented in the pre-Mongol Persian Documents from Ghur." Afghanistan 4, no. 2 (2021), 91-113.

Lambton, Ann K. S. Landlord and Peasant in Persia: A Study of Land Tenure and Land Revenue Administration. [1st ed.] reprinted (with new preface and additional bibliography). London: Oxford University Press, 1969.

Lowry, Heath W. The Nature of the Early Ottoman State. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2003.

Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ʿAlī al-Nasawī. Sīrat al-Sulṭān Jalāl al-Dīn Mankubirtī, translated by Octave Houdas as Histoire du sultan Djelal-ed-Din Mankobirti, prince du Kharezm par Mohammed-en-Nesawi. E. Leroux: Paris, 1895.

Muḥammad ibn Ibrāhīm, Tārīkh-i Kirmān: Saljūqiyān va ghaz dar Kirmān, edited by Muḥammad Ibrāhīm Bāstānī Pārīzī. Tehran: Kitābfurūshī-i Ṭahūrī, 1964.

Muntajab al-Dīn Badīʿ. Kitāb-i ʿatabat al-katabah: majmūʿah-i murāsalāt-i dīvān-i Sultān Sanjar, edited by Muḥammad Qazvīnī and ʿAbbās Iqbāl. Tehran: Shirkat-i Sahāmī-i Chāp, 1950.

Rustow, Marina. The Lost Archive: Traces of a Caliphate in a Cairo Synagogue. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020.

Stern, S. M. Fāṭimid Decrees: Original Documents from the Fāṭimid Chancery. London: Faber and Faber, 1964.

Turan, Osman. Türkiye Selçuklulari hakkinda resmî vesikalar. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Basimevi, 1958.

Uzunçarşılı, I. Hakki. "Gazi Orhan Bey Vakfiyesi." Belleten (Türk Tarih Kurumu) 5, no. 19 (1941), 277-288.

This Document of the Month was updated on 27 January 2025 to reflect a superior reading of the signature suggested by Boris Liebrenz (Saxon Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Leipzig).

Cite this article

Shawe-Taylor, E. 2025. “Nishān, ʿAlāma, or Ṭughrā: a Case Study from the Firuzkuh Papers.” Document of the Month. Invisible East. doi: 10.5287/ora-2rq2zjdgw.

About the author

Edward Shawe-Taylor is Invisible East's Assistant Database Manager for our Digital Corpus. He is writing his thesis on medieval manuscripts of Jaḥiẓ’s Kitāb al-Ḥayawān. His other research interests include Islamic book production before the Mongol invasions, the tirāz textile industry in the medieval Mediterranean and illustrated bestiaries from the Mamlūk and Ilkhanid periods.

The online series, Document of the Month, presents some of the most interesting and revealing medieval documents from the desks of Invisible East researchers and their colleagues worldwide. Each piece in the series is dedicated to a single document or a closely related group of documents from the Islamicate East and tells their story in an engaging and accessible way. You will also find images, editions and translations of the documents. If you would like to contribute to the Document of the Month series, please, get in touch with Nadia Vidro.