Fīrūzkūh Papers: Pre-Mongol Persian Documents from Today’s Afghanistan

Fīrūzkūh Papers: Pre-Mongol Persian Documents from Today’s Afghanistan

by Nabi Saqee, November 2024

The Fīrūzkūh Papers comprise of 101 documents in Persian from the pre-Mongol era, that is, from the end of the Ghūrid and the Khwārazmshāh periods (mid-12th to early 13th century of the common Era). These documents were discovered in 1991 by locals around the Shahr-i Khurū village1 in the Ghalmīn district, 45 km north of Fīrūzkūh city, the capital of the Ghūr province.

During the Soviet – Afghan War (1979–1989), when rural areas of Afghanistan had no government, illegal excavations for gold were common throughout the country. In 1991, some people from the village of Shahr-i Khurū went looking for treasure in the caves near their village in the heart of the mountain, but instead of gold they found a collection of old papers. They did not know what these papers were.

The first to appreciate the value of their discovery was Mīrzā Khwāja Muḥammad, one of the cultural scholars of Ghūr, who had taken refuge in Ghalmīn from the Kāsi village. When Mīrzā Khwāja Muḥammad learned about the documents, he purchased them from the local people and preserved them in his notebook.

In 2020, Mīrzā Khwāja Muḥammad handed over the Fīrūzkūh Papers to the government and to the then President of Afghanistan.3 The documents are currently housed in the National Archive of Afghanistan.

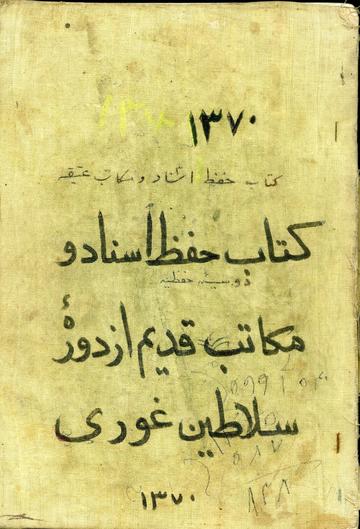

The cover of Mīrzā Khwāja Muḥammad's notebook for the year 1991, in which the documents were initially preserved.

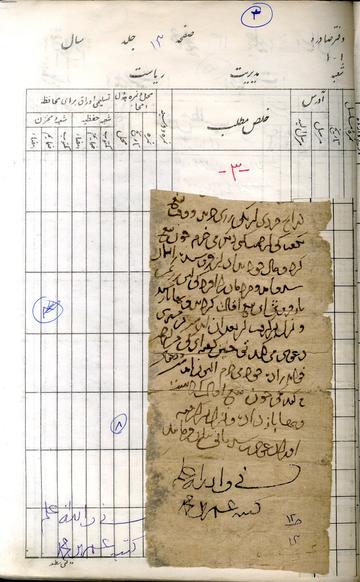

A Fīrūzkūh document pasted into Mīrzā Khwāja Muḥammad's notebook, with Mīrzā Khwāja Muḥammad's annotations.

The publication of the Fīrūzkūh Papers

In 2009, Mīrzā Khwāja Muḥammad and Nabi Saqee re-read the Fīrūzkūh Papers and published them in Afghanistan.4 This initial publication made the documents accessible for the first time, but it lacked a commentary and an in-depth analysis. Since 2021, researchers in the Invisible East programme have been working on translating into English, analysing and digitising the Fīrūzkūh documents, and on comparing them with the Bamiyan Papers.5 Annotated editions and translations of the documents can be found in the Invisible East Digital Corpus. A study of the Fīrūzkūh Papers will be published by Ofir Haim, Nabi Saqee and Arezou Azad in a monograph on economic life in medieval Ghūr, to appear in The Islamicate East series of Edinburgh University Press.

In 2023, the Invisible East team directly engaged with local residents of the Shahr-i Khurū village and inteviewed people who were inside the cave on the day when the Fīrūzkūh Papers were found. A short documentary film was subsequently produced, featuring firsthand accounts of the papers’ discovery and expert assessments of the documents.

https://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/HyhBiY7_hG8?si=8kxv6Ldvf1dvomJz

Geography and place names

The Fīrūzkūh Papers were found in an area situated between the Harīrūd and Murghāb rivers. This region was a part of the territory of Ghūr, during the reign of the Ghūrids,6 but due to its proximity to the Murghāb River, it may be a part of the historical Ghajīstan region.7

In total, 45 place names have been identified in the Fīrūzkūh documents. 23 of these places still retain their medieval names, but the other 22 names have either changed or disappeared completely. Some of the place names, such as Hindustan (India), Khurasan, Iraq, Ghazna, Ṭūs, Balkh, Maimana, Kalīwūn, and the like, either appear indirectly in names and titles, or are mentioned in letters. But other place names, such as Murghāb, Sparf, Tagab-i Tāq, Fīrūzkūh, Bardīz, Kurgīn, Shārstay, Khāī, Nilīnj, Spalīzh and Darṭakh, are related to the area where the documents were found. Tithes, payment orders or events mentioned in the documents are connected to these villages.8 These places are located in the Fīrūzkūh, Murghāb and Chahārsada districts of the Ghūr province and have preserved their medieval names until today.

Language and dialect

The language of the Fīrūzkūh Papers is New Persian. The documents exhibit a literary form and official style and were written before modern-day local dialects developed. Despite this, certain words that appear in the Fīrūzkūh Papers are uncommon in the dialect of Kabul or Tehran today but are widely used in the dialect of Ghūr. These are, for example, shīshak (one-year old male sheep), chapush (one-year old female goat), mal (deer), mīsh (sheep), jawāna gāw (one-year old bull), kafchalīz (skimmer), tirmāhi (autumnal) and karat (time).9 These words connect modern speakers of the dialect of Ghūr with the Papers of Fīrūzkūh.

Typology of Fīrūzkūh documents

The Fīrūzkūh Papers include legal documents (purchase and sale of real estate, family matters, inheritance and loan documents), administrative documents (tithes, taxes, remittances and lists), government and personal correspondence, and jurisprudential queries and responses. In addition, there are fragments of the Qurān, religious treatises and literary texts.

Administrative documents

Out of the 101 documents, circa 41% are classified as administrative documents. They deal with taxes, tithes and remittances, often paid in such key commodities as wheat, barley, and straw. Twenty of these documents are linked to a state department known as al-Dīwān al-Ikhtiyārī.10 Although historical literature of the Ghūrid period does not mention the Dīwān al-Ikhtiyārī, it is evident from the Fīrūzkūh Papers that this department handled matters related to taxes and storage facilities.

Notable figures who appear in the documents are muqaddams and khwājagān (village headmen)11 and the muʿtamid (trustee) or storekeeper.12 The muqaddams and khwājagān, mentioned eight times in the documents,13 served as intermediaries between the Dīwān al-Ikhtiyārī and the community. The title muʿtamid is found in 20 instances in connection with a person named ʿAlī b. ʿAbd al-Rashīd, who communicated governmental directives to muqaddams and khwājagān as well as to the local populace. Two other muʿtamīds, ʿAlī-i Silāhdār (mentioned twice) and Muḥammad b. Maḥmūd (mentioned once), also appear in the Fīrūzkūh Papers.14

Conclusion

The Fīrūzkūh Papers represent significant and rare Persian documents from the pre-Mongol period, discovered in eastern Khurasan (modern-day Afghanistan). In conjunction with the Bamiyan Papers, many of which also date to the Ghūrid period, the Fīrūzkūh Papers offer valuable insights into the political, social, agricultural, and everyday lives of common people in medieval eastern Khurasan during this historical epoch. While some research has already been done on these documents, much of it is introductory. The Invisible East team's ongoing work on the Fīrūzkūh Papers will continue to enhance our understanding of these important documents.

Notes

1 See Geo Names: Shahr-e Khurō, Afghanistan (geonames.org)

2 Khwāja Muḥammad and Nabi Saqee. Barg-hā-ī az yak faṣl ya asnād-i tārīkhī-yi Ghūr. Kabul: Intishārāt-i Saʿīd, 1388/2009.

3 On this handover, see گزارش بیبیسی اسناد تاریخی قبل از حمله مغول را از غور به ارگ رساند - BBC News فارسی

4 Muḥammad and Saqee, Barg-hā-ī.

5 On the Bamiyan Papers, see Ofir Haim,“What is the ‘Afghan Genizah’? A Short Guide to the Collection of the Afghan Manuscripts in the National Library of Israel, with the Edition of Two Documents”, Afghanistan 2/1 (2019), pp. 70-90, Husseini, “The Muqaddam”, pp. 96–98, Majid Montazer Mahdi, “Introduction to the study of Persian documents (in Persian)”, Blog of the Invisible East Programme, 8/08/2022.

6ʿAbd al-Ḥayy Ḥabibī (ed.), Ṭabaqāt-i Nāṣirī by Minhāj al-Sirāj al-Jūzjānī, vol. 1, Kabul: Education Press, 1963 [in Persian], p. 349.

7 Ludwig W. Adamec, Historical and Political Gazetteer of Afghanistan, vol. 3. Graz: Akadem. Druck- u. Verlagsanst, 1975, p. 272 and Muḥammad and Saqee, Barg-hā-ī.

8 See Afghanistan National Archives, Firuzkuh 6, 4, 7, 8, 13a, 13b,14a, 15a, 18, 30, 32, 34, 39, 41, 50, 54, 57a, 61, 63, 64a, 65, 75r, 77r. Document numbers refer to the Invisible East Digital Corpus (Collection: Afghanistan National Archives).

9 See Firuzkuh 4, 14a,15, 38, 53r, 56, 58,72, 80.

10 See Firuzkuh 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47b, 49, 93. See also Huseini, “The Muqaddam”, pp. 105–106.

11 Huseini, “The Muqaddam”, pp. 103–104.

12 Huseini, “The Muqaddam”, pp. 102–103.

13 See muqaddams in Firuzkuh 30, 32, 34, 36, 39, 47a, 65, 75r.

14 See Firuzkuh 28, 37, 46.