Format, Style and Politeness Strategies in Middle Persian Official Letters from 7th-Century Egypt

Format, Style and Politeness Strategies in Middle Persian Official Letters from 7th-Century Egypt

by Narges Nematollahi, May 2023

It is well known that letters can provide a wealth of information about the socio-political and economic situation of the society from which they come. The huge corpus of Greek letters from Greco-Roman Egypt has enabled historians to reconstruct different aspects of social and political life in Egypt in that period. Lewis (1983) and Verhoogt (1998) are two examples of such studies. The corpus of Middle Persian letters from late Sassanid and early Islamic period is not comparable in terms of size with the Greek corpus, but still it has proven helpful in shedding some light on the political and social situation in Sassanid Egypt and in Central Iran.1 But what further information can letters from ancient societies reveal? Letters as half-dialogues between people, often of different social ranks can disclose the social etiquette and politeness norms that predominate in a society. The ways in which the authors refer to themselves and their addressees, variations in greeting phrases depending on the social rank of recipients, and strategies to frame the order or request and to encourage its fulfilment, are all clues that help us to detect the various aspects of social interaction in a culture from which the letter comes. In this blog, I look at the format and linguistic style of Middle Persian documentary letters that were exchanged between Sassanid state officials in Egypt, focusing on the features that reveal politeness norms in Sassanid Iran

In describing the politeness strategies, I mainly use the Brown and Levinson model in which the general principle of politeness is formulated as follows: “people cooperate and assume each other’s cooperation in maintaining face”.2 This principle requires that face-threatening acts (FTA) (e.g., requests which intrinsically threaten the face of the hearer (H) or apologies which threaten that of the speaker (S)) be redressed or mitigated to lower the risk of the threat. Politeness strategies develop in each culture and language to do just that, i.e., to redress or mitigate the FTAs. Brown & Levinson formulate several politeness maxims, e.g., “Don’t coerce H,” and then provide various linguistic strategies which fulfil the maxim, e.g., using questions or hedges (e.g., Could you please do this? or If you see it fit, do this! instead of Do this!).

Pahlavi Papyri from Egypt3

These documents, mostly written on papyri but also on parchment and linen, were found in Egypt’s Fayyūm oasis in the 19th century and relate to a ten-year occupation of Egypt by the Sasanian king, Khosrow II (590-628 CE), between 619 and 629 CE. Weber (2008) estimates the number of the documents to be around 1,000, the majority of which survived only in fragments. Many of the documents seem to be letters: both family and official letters. I will focus in this blog on one official letter (P. 136). 4

To Yazdānkard about the arrival of a high official to a certain village

|

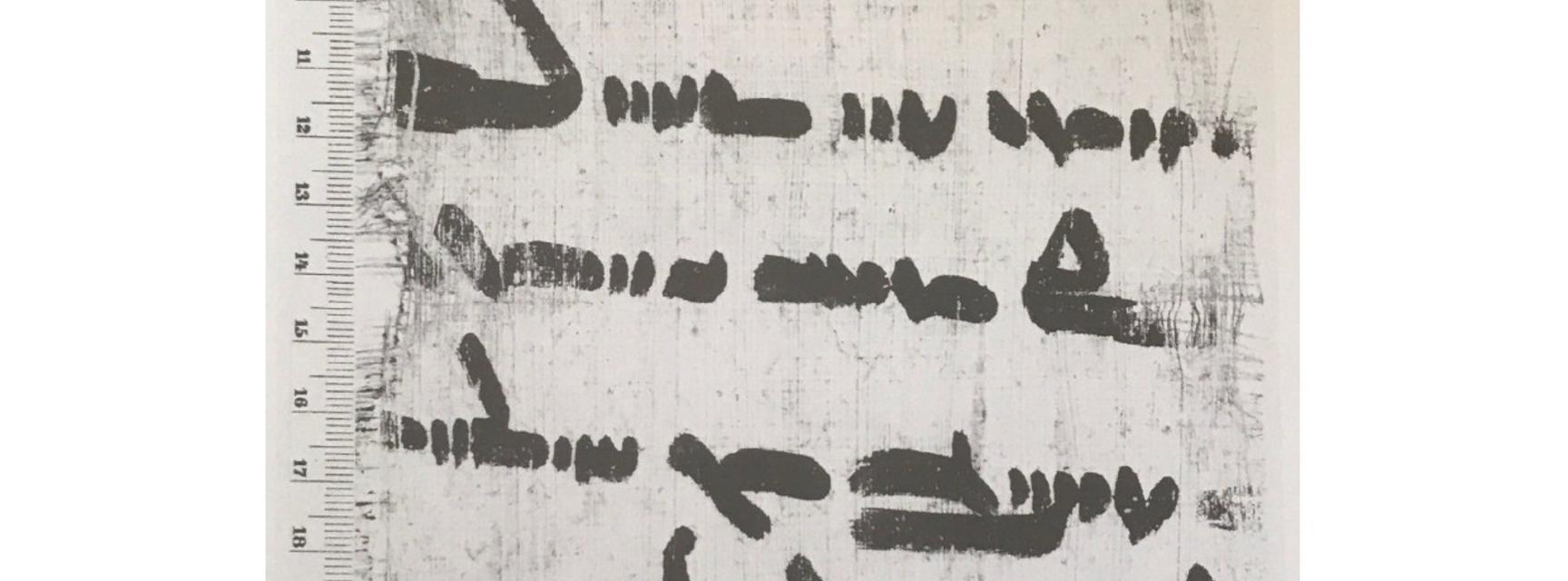

Praescriptio |

(ō) xwadāyīg Yazdānkard namāz |

|

Greeting |

hus]rawīh drōd ud drustīh ud rāmišn ud har]w farroxīh abāg passand ud hušnūd]īh ī amāh būd hamē pad] xwadāyīg pad abzōn rāy ba]wād |

|

Body |

āgāhīh ī xwadāyīg rā]y nibēsēm kū Šahr-Ālānyōzan fra]dāg rōz Anagrān ō deh ī] ṭwrṭ' widerišn ēstēd xwadāyīg ud] gundsālārān ud āzād-mardān ud aswārān [xwē]š fradāg rōz Anagrān … ].. az deh ī ʼplhʼm ] az kust čiyōn abāyēd ] padīrag ē āyēd …. |

|

Praescriptio |

To lordly Yazdānkard, reverence! |

|

Greeting |

May the good reputation, well-being and health and ease and every fortune with pleasure and contentment which we possess, may it be always with the lord in increase. |

|

Body |

For the knowledge of the lord I am writing that tomorrow on the day of Anagrān, Shahr-Ālānyōzan will pass by the village of ṭwrṭ. May tomorrow the day of Anagrān, the lord and the army officers and the noble men and the cavalry from the village of ʼplhʼm … from the district, …. come to welcome (him) as is fitting. …. |

We can identify three sections in the letter: the praescriptio, the greeting, and the body.

Praescriptio

The format of the praescriptio is: to X RECIPIENT, reverence!, in which X stands for one or several honorifics used for the addressee. The honorific used in this letter is xwadāyīg (“lordly”), which is the adjectival form of xwadāy (“lord”). We see other honorifics such as yazdānayād (“remembered by the gods”), and yazdān hamē farroxtar kard (“made ever fortunate by the gods”) in other letters. The word translated as “reverence” is the Middle Persian namāz, which in the literature denotes the extremely polite gesture of bowing down when in the presence of deities and kings. In Middle Persian letters, however, namāz serves as the common deferential phrase which is used in letters to all sorts of recipients: subordinates, superiors, and peers alike.5 How do we characterize the function of the honorifics and the phrase namāz in addressing the recipients? One of the politeness maxims discussed by Brown & Levinson is ‘Give deference to the hearer,’ which can be achieved through humbling the self, and/or elevating the hearer. Giving deference ensures that “S (= the speaker) is certainly not in a position to coerce H’s compliance in any way,” and thereby lowers the risk of the FTA (which in the case of most administrative letters is a request).6 The Middle Persian format for praescriptio gives deference to the recipient by raising them through honorifics, as well as by lowering the sender through the term namāz.

Greeting

The greeting is a full sentence consisting of several abstract nouns (e.g., husrawīh “good reputation,” drōd “well-being,” hušnūdīh “contentment”) and intensifying modifiers (e.g., hamē “always”, pad abzōn “in increase”). In the greeting sentence, the singular author (judging from his use of nibēsēm “I write,” later on in the body of the letter) uses amāh “we” in reference to himself and xwadāy “lord” in addressing the recipient. This use of pronouns feels more polite or more formal than if the author used man “I” and tō “(singular) you.”

But why is that? In an interesting article entitled “Two’s Company, Three’s a Crowd,” Bean (1970) applies the theories of politeness to pronoun usage in various languages and argues that the use of plural pronouns in place of singular transforms the interaction from a dyad to a triad. This transformation removes the intimacy between the two parties and creates a social distance, which in turn, develops a sense of deference or respect. The greeting sentence in this letter maximizes the distance between the sender and recipient by using a plural pronoun for the sender and third-person pronoun for the addressee. This explains the extremely polite and formal feature of the greeting. In the body of the letter also we see that the addressee is referred to not directly through some forms of second-person pronouns, but rather indirectly in the third person through the term xwadāyīg (”lord”).7

The request is expressed in the optative mood in the second-person plural, ē āyēd (“may you [please] come”), as opposed to the imperative form. The use of optative which, by definition, gives the hearer the option not to act, is a politeness strategy that falls under the maxim, ‘Don’t coerce H,’ in the Brown and Levinson model.

Body and the Address of the Letter

P. 136 is too fragmentary towards the end, but we know through other letters that the body is followed by a section in which the name of the sender is mentioned after that of the recipient.8 An example of this section, called the “address section” is given below. It has a similar format to the praescriptio (to X RECIPIENT, reverence!) with the name of the sender following the namāz.

|

ō yazdān hamē farroxtar kard pad hazār anōšayād Dādrōy ī ... ī Xusrōdādān namāz Māhtēx [?] ī aswār (P. 70) |

|

To whom the gods made ever fortunate, ever-remembered for thousand times, Dādrōy …. son of Khosrowdād, reverence! (From) Māhtēx the horseman. |

Basic Layout

This table summarizes the basic layout of Middle Persian official letters from Egypt:

Politeness Strategies in the Aramaic Tradition of Achaemenid Iran

The degree of politeness in Middle Persian epistolary tradition is more pronounced when we compare Middle Persian official letters with official letters in Aramaic from the Achaemenid period. In the Aramaic tradition the following applies:

- The only honorific used for the addressee is mr’ (‘lord’) which is used only for high officials.

- There is no word corresponding to namāz (‘reverence’), and unlike the Middle Persian tradition which includes greetings in all the letters, in the Aramaic tradition letters to subordinates have no greetings.

- The author uses the first singular pronoun to refer to himself, and the second person singular in addressing the recipient. Superior recipients may be occasionally addressed as mr' (‘lord’).

If we compare the greeting sentence in the Aramaic and the Middle Persian traditions, we find that the general structure is the same: the sender reassures the recipient about his own well-being and wishes the recipient well. However, the Middle Persian version is characterized by the use of reverential we for the sender, and honorific (‘lord’) for the recipient, as opposed to ‘I’ and ‘you (singular)’ in Aramaic. Also, it is more verbose by including several abstract nouns in addition to just ‘peace’ and ‘prosperity’ in Aramaic. Finally, it uses modifiers, such as, ‘always’ and ‘in increase’ to intensify the sender’s wish.9

Aramaic

|

שלם ושררת שגיא הושרת לך וכעת שלם בזנה קדמי אף שלם תמה קדמיך יהוי |

|

I send you much peace and prosperity! And now, (there is) peace here before me. May there also be peace there before you (singular). |

Middle Persian

|

husrawīh drōd ud drustīh ud rāmišn ud harw farroxīh abāg passand ud hušnūdīh ī amāh būd hamē pad xwadāyīg pad abzōn rāy bawād |

|

May the good reputation, well-being and health and ease and every fortune with pleasure and contentment which we possess, may it be always with the lord in increase. |

All these features are familiar to people who know about the concept of ta‘arof in the culture of present-day Iran. So if you ever wondered about the roots and development of this cultural practice among Iranians, Middle Persian letters are a promising point to start.

Notes

1See Gariboldi (2009), Gignoux (2009), Weber (2010, 2011) among others.

2 Brown and Levinson (1987: 61). The concept of face in this model is adopted from Goffman and defined as follows: “the positive social value a person effectively claims for himself.” (Goffman 1955: 213)

3 The collection of Pahlavi papyri from Egypt is now scattered in various libraries and museums, largely in Europe. Weber (1992) and Weber (2003) provide an edition of around 350 of them. For the inventory of Middle Persian documents from Iran, see the entry by Thomas Benfey here

4 The numbering and the edition of the text follow Weber (2003).

5 It is noteworthy that in Middle Persian literature (Book Pahlavi),namāzis usually written as an Aramaic heterogram, i.e., ‘SGDH. In Middle Persian letters, however, it is written in an abbreviated form, i.e., nc. The different writing conventions for this phrase further suggest its varying usage in Middle Persian literature vs. in the epistolary tradition. See Nematollahi (2019: 246-48) for a more detailed discussion.

6 Brown & Levinson (1987: 178).

7 As the adjectival form of xwadāy (“lord”), xwadāyīg is usually used as an honorific term meaning (“lordly”), similar to its usage in the praescriptio of P.136. However, there are cases in which xwadāyīg as a substantivized adjective is used interchangeably with xwadāy (Weber 2007).

8 P.70, P.75, P.80, P.109 and P.305 include the address sections. Among these letters, P.70, P.75 and P.305 have only the address section preserved, and thus, they do not reveal the position of the address within the entire letter. P.80 and P.109 are more complete and have the address section following the body (P.80 has one blank line in between the body and the address, in P.109, address starts a new line right after the body).

9 One of the major characteristics of politeness is that it is subject to gradation, so we have more and less polite expressions (Leech 2014). One principle noted in the literature which makes an already polite utterance even more polite is that the longer the utterance is, the more polite it is felt to be. See Martin (1964: 411) for Japanese and Wardhaugh (2010: 298) for French.

References

Bean, S. 1970. “Two’s Company, There’s a Crowd” American Anthropologist 72, pp. 562-564.

Brown, P. & S.C. Levinson. 1987. Politeness: Some Universals in language usage (re-issue of Brown & Levinson (1978) with corrections, new introduction, and new bibliography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gariboldi, A. 2009. "Social Conditions in Egypt under the Sasanian Occupation." La parola del passato: rivista di studi antichi 64. pp. 335-350.

Gignoux, P. 2009. “Les comptes de Monsieur Friyag: Quelques documents économiques en pehlevi",in R. Gyselen (ed.) Sources pour l’histoire et géographie du monde iranien (224-710) (Res Orientales XVIII), pp.115-142.

Goffman, E. 1955. “On Face-work: An Analysis of Ritual Elements in Social Interaction”, Psychiatry 18, pp. 213-231.

Leech, G. 2014. The Pragmatics of Politeness. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Lewis, N. 1983. Life in Egypt under Roman Rule, Oxford, New York: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press.

Martin, Samuel. 1964. “Speech levels in Japan and Korea”, in D. Hymes (ed.) Language in culture and society. New York: Harper and Row. pp. 407-415.

Nematollahi, Narges. 2019. “The Iranian Epistolary Tradition: Origins and Developments (6th century BCE to 7th century CE)”, PhD dissertation, Indiana University.

Verhoogt, A. M. F. W. 1998. Menches, Komogrammateus of Kerkeosiris: The Doings and Dealings of a Village Scribe in the Late Ptolemaic Period (120-110 BC), Leiden; New York; Köln: Brill.

Wardhaugh, R. 2010. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics (6th edition). Wiley-Blackwell.

Weber, D. 1992. Ostraca, Papyri und Pergamente: Textband (Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum. Part III: Pahlavi Inscriptions. Vol. iv. Ostraca and Vol. V. Papyri. Texts I). Cambridge University Press on behalf of School of Oriental and African Studies

Weber, D. 2003. Berliner Papyri, Pergamente und Leinenfragmente in mittelpersischer Sprache (Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum, part III, vol. IV-V). London: School of Oriental and African Studies. Unter Mitarbeit von W. Brashear.

Weber, D. 2007. “Remarks on the development of the Pahlavi script in Sasanian times”, in F. Vahman, C.V. Pedersen (eds.) Religious Texts in Iranian Languages (Akten des Kongresses Kopenhagen 2002), København: Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab. pp. 185–195.

Weber, D. 2008. “Sassanidische Briefe aus Ägypten”. Asiatische Studien/Études Asiatiques LXII(3). pp. 803–826.

Weber, D. 2010. “Villages and Estates in the Documents from the Pahlavi Archive: The Geographical Background”, Bulletin of the Asia Institute, New Series, Vol. 24, pp.37-65.

Weber, D. 2011. “Testing Food and Garment for the "Ōstāndār": Two Unpublished Documents from the "Pahlavi Archive" in Berkeley, CA”, Bulletin of the Asia Institute, New Series, Vol. 25, pp. 31-37.

About the author

Narges Nematollahi is the Elahé Omidyar Mir-Djalali Assistant Professor of Persian Language at the University of Arizona, Tucson.