Rural Administration, Society and Economy in the Bamiyan Area - Part 1

Rural Administration, Society and Economy in the Bamiyan Area: The Story told by the Barāt Documents in the Bamiyan Papers

by Arezou Azad, 11 November 2022

** Contents of this blog will appear in a volume that is currently being prepared for publication by Arezou Azad and Pejman Firoozbakhsh. **

Part 1: "The Documents"

1. The context: overcoming the imperial history paradigm and turning to the grassroots

The history of the first five hundred years of Islamic rule in the eastern Islamicate lands (in what is today Iran, Afghanistan, and Central Asia) from the 8th century Arab conquests to the 13th century Mongol takeover has typically been told through the eyes of court historians and religious scholars. Many of the authors of these texts were based in large urban centres, and in faraway places like Syria and Egypt. As important as these narratives are, they tell us little about the private or public lives of ordinary people: cobblers, shopkeepers, lower and middle-rank officials, non-royal women, slaves, tax collectors, and so on. The focus of the Invisible East programme on documents—contracts, administrative documents, private letters, etc.—is putting the spotlight on ordinary people. This blog is a preview of some of the findings from our study of the fascinating “Bamiyan Papers.”

2. The archive of Abū Bakr ibn ʿUmar

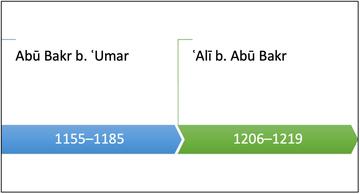

Of the 200+ sheets in the Bamiyan Papers that are accessible on the www.nli.il (called “Afghan Geniza” on the website), some 47 sheets have something in common. They were all issued by a certain Abū Bakr ibn ʿUmar and an ʿAlī ibn Abū Bakr, who appears to be the former’s son. From references to them as anbār-dār, we know that both men worked in a royal store house (anbār-i khāṣṣa) that collected grains as taxes. Together their service spanned seventy years from 1155 to 1219 CE; which coincides with the Shansabānī (Ghūrid) rule, followed by Khwārazmshāhī rule in the Bamiyan area.

Diagram 1: Timeline of the two warehouse managers

The original location of the archive is still uncertain due to the lack of precise information regarding the Bamiyan Papers’ provenance, but at least four place names mentioned in them point to the region between Bamiyan and Ghurwand (today, ca. 120 km apart). The region falls within the eastern extension made to the Bamiyan sultanate under the Ghurid sultan Shams al-Dīn Muḥammad (r. 558-88/1163-92), approaching the modern-day border of Afghanistan with Pakistan. If this georeferencing is correct, then the Bamiyan Papers offer us a unique first-hand insight into the way an area that later become a contested border area between the Mongol Ilkhānate and the Delhī Sultanate, and lies at a geostrategic faultline between Afghanistan and Pakistan today, was administered.

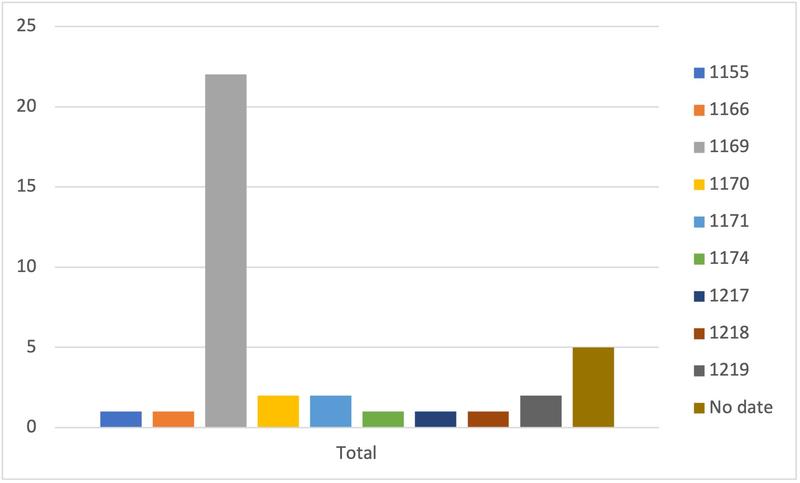

The chronological distribution of the documents is uneven, with a large majority issued in a single year (1169 CE). We have identified four types of documents amongst the 47 warehouse documents: 1) receipts (type-1 barāt), 2) cheques (type-2 barāt), 3) legal declarations (iqrār), and 4) internal state correspondence and lists.

Diagram 2: Timeline of Surviving Documents Issued by the Office of Abū Bakr b. ʿUmar and ʿAlī b. Abū Bakr

3. Two Types of barāt in the Warehouse Archive

Type 1:

The largest proportion of administrative documents issued by Abū Bakr b. ʿUmar and his son consisted of what my colleague Pejman Firoozbakhsh and I call a type-1 barāt, i.e. a quittance or receipt. Thirty-five such receipts made it into this set and were issued over an extended period of 38 years (1169-1207 CE); although 22 of them (58 %) were issued in the year 564-5/1169 alone by Abū Bakr b. ʿUmar who also issued receipts in 1170 and 1171 CE. Receipts were also issued in 1183 and 1185 CE, at which point Abū Bakr’s son ʿAlī had already taken over warehouse management. These seem to have been handed over by the warehouse managers to the taxpayers directly, while it is the copies that were retained in the warehouse archives that have survived.

Barāt (a Persian term, derived from the Arabic barāʾa) is a type of document that is well attested across Islamicate documentary sources. It is a formal note that acknowledges the receipt of a payment or a delivery, in this case in relation to tax contributions. The Arabic Papyrology Database encompasses many dozen tax-related barāt documents issued in Arabic mainly in Egypt between the years 700 and 1100 CE. The ʿAbbāsid historian Ibn Miskawayh refers to the barāt type of document in the 10th century in respect of instalments paid in relation to the word rūz (day). Barāt appears in the eastern Islamic Mafāṭiḥ al-ʿulūm from the Sāmānid period (900s CE) when its author used it specifically to denote “an assignment of pay from a specific estate or source” (Bosworth 1969: 124). And it occurs again in this sense in early Ghaznawid times, e.g., in Bayhaqī’s Tārīkh-i Masʿūdī.

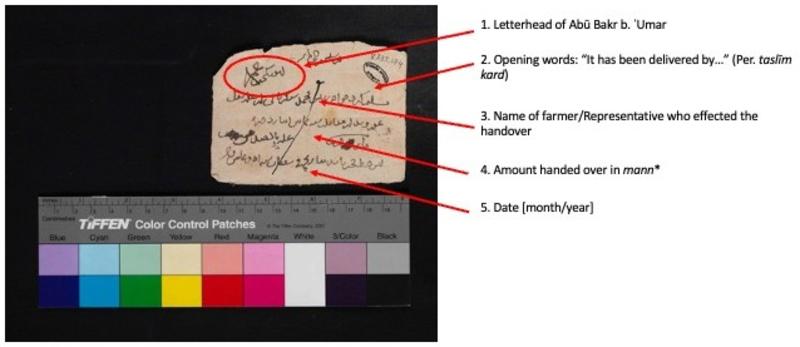

The structure of the NLI barāt is pretty uniform and simple, and many of the delivery records were written in the same hand, probably belonging to the managers themselves. The stylised font (larger and set apart from the rest of the text) in which their names appear is reminiscent of—and seemingly a precursor to—the more elaborate tughras or tawqīʿs (calligraphic emblems of rulers affixed to documents) found on some of the other medieval documents from Fīruzkūh area of Afghanistan. The latter were issued on documents coming from the higher chancelleries (Per. dīwān), such as a dīwān-i ʿālī, dīwān-i marāʿī, dīwān-i ʿarḍ, and dīwān-i ikhtiyārī, as well as, by the office of a judge on a court record.

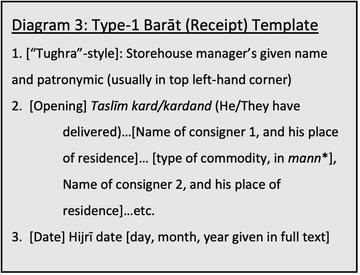

The content in the NLI barāts is formulaic and follows with two main statements: the name of the consigner and his place of residence and the volume or value of the commodity that is delivered. A closing statement gives the date. The schematic template is this:

Type 2

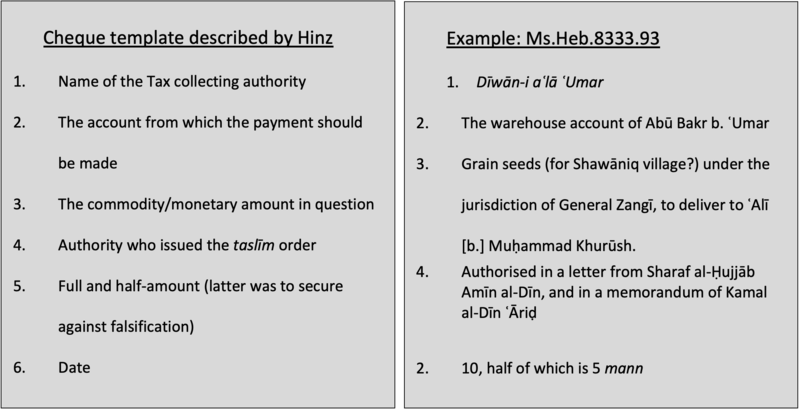

The second type of barāt in the archive is the cheque. Cheques appear three times in the archive and were issued by a dīwān-i ʿalā/ʿālī ( Ms.Heb.8333.91, Ms.Heb.8333.93 and Ms.Heb.8333.94), which perhaps consisted of the imperial finance authority and was headed by the grand vizier. (The terms ʿalā and ʿālī both appear: ʿalā would just be a preposition “over” and so seems odd by itself; ʿālī means “high”). The imperial finance authority, in turn, had three heads of department: the mustawfī (the finance department), mushrif (accountancy department) and nāẓir (the inspector, auditor). The cheque follows almost the same structure of the Steuerscheck (“tax cheque”) described by Walter Hinz based on accountancy 14th-century Persian accountancy manuals such as the Ṣaādatnāma and the Risāla-yi Falakiyya (with minor variations):

Diagram 4: Schematic template of cheques in the NLI set and compared to Hinz’s schema

4. Document Archiving and Recycling

We noticed that the recto (front) and verso (back) sides of the folios were often not part of the same document. They were different documents written at different times by different people. Paper was valuable, and so sheets were reused, just like the Fatimid-era documents of the Cairo Geniza were reused by synagogue officials (for a recent discussion, see Rustow 2020). From a number of the verso sides of the sheets from the office of Abū Bakr b. ʿUmar and his son ʿAlī, we identified internal state correspondence and lists, presumably decommissioned by the relevant ministry, and then reused by the warehouse.

What did the warehouse do with the barāts? On many of these sheets we find notes made in a new hand after the issuance and filing of the documents. For example we see a diagonal line drawn over the receipts (see photo above). The line may have been drawn as a note-to-self by the accountant as he was comparing and recording amounts in an adjacent ledger. The ledger may have listed the tax rates for each particular district and the accountant might have been checking the incoming against the balance. Another possibility is that the accountant was recording the incoming in the day book (rūznāmaj), much like it is prescribed in the near-contemporary Persian accountancy manual Riṣāla-yi Falakiyya1.

---

1The Risāla-yi Falakiyya was first recognised in an article by Turkish scholar A.Z.V. Togan, in his article, “Mogollar devrinde Anadolu’nun iktisadî vaziyeti (The Economic Situation in Mongol-Era Anatolia),” in Türk Hukuk ve İktisad Tarihi Mecmuası 1 (Istanbul: Evkaf Matbaasi,1931), 3-6, 14-15.

---

About the author:

Arezou Azad is Senior Research Fellow at the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Oxford, PI and Director of the Invisible East programme.

---

Selected bibliography

Bosworth, C. Edmund. “Abū ʿAbdallāh al-Khwārazmī on the Technical Terms of the Secretary's Art: A Contribution to the Administrative History of Mediaeval Islam.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 12/2 (Apr.,1969).

Hinz, Walther. “Das Rechnungswesen orientalischer Reichsfinanzämter im Mittelalter,“ Der Islam (1950), 1-29.

Hinz, Walter, Die Resala-ye Falakiyye des 'Abdollah Ibn Mohammad Ibn Kiya al-Mazandarani. Ein persischer Leitfaden des staatlichen Rechnungswesen (um 1363) (Wiesbaden, 1952).

Lambton, Ann K.S. Landlord and Peasant in Persia: A Study of Land Tenure and Land Revenue Administration (London: I.B Tauris, 1991 [1953]), xiii-xxxi, 1-76.

Lambton, Ann K.S. Continuity and Change in medieval Persia: Aspects of Administrative, Economic and Social History, 11th-14th Century (London: I.B. Tauris, 1988).

Nabipour, Mirkamal. Die beiden persischen Leitfaeden des Falak ʿAlā-ye Tabrīzī ueber das staatliche Rechnungswesen im 14. Jahrhundert, Goettingen 1973.

Rustow, Marina. The Lost Archive: Traces of a Caliphate in a Cairo Synagogue (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020).

Spuler, Bertolt. Die Resalä-ye Falakiyyä des 'Abdollah ibn Mohammad Ibn Kiya al-Mazandarani (Book Review) in: Der Islam 31 (Jan 1, 1954): 260.