Document of the Month 2/25: A Land Sale Deed in Old Uyghur

How to 'Acknowledge' a Land Sale in Old Uyghur:

An Iqrār Document from Qarakhanid Yarkand

by Mateen Arghandehpour

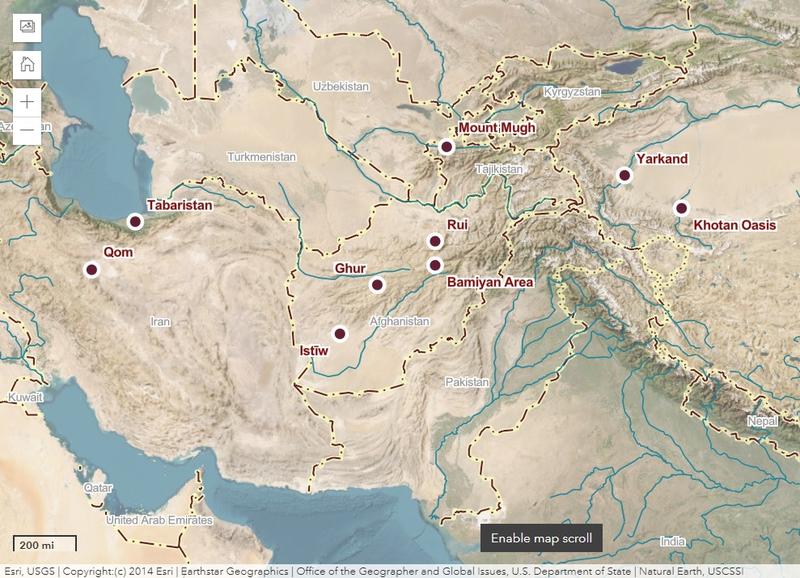

This month’s document comes from a cache of documents discovered in a garden on the outskirts of modern Yarkand, in today’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China, at the southwestern end of the Tarim Basin. Found in 1911, the documents went missing again, and only the photographs of some of them are available. (To learn more about the discovery and fate of the documents, read this blog.)

Map 1. Yarkand can be found on the Yarkand River. Above snapshot is taken from the interactive map on the homepage of this website.

Between ca. 1041-1210 CE, Yarkand was part of the Eastern Qarakhanid Khanate. The Qarakhanids were the first Muslim Turkic dynasty, and the Qarakhanid Khanate was ruled by a Muslim ruler from 955 CE. The Khanate split into eastern and western parts in c. 1041 CE, roughly separated by the Tien Shan mountain range.

Map 2. Qarakhanid Khanate as of 1006 CE, when it reached its greatest extent; By SY - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=68158198

Yarkand legal documents

The Yarkand collection consists of 11th- and early 12th-century legal documents in Arabic and Old Uyghur. All of the Old Uyghur documents are land sale contracts. As observed by Yarkand documents' editors Marcel Erdal and Monika Gronke, these documents demonstrate clear similarities with contemporary Arabic deeds of land sale. At the same time, they differ significantly from their non-Muslim Turkic counterparts, which according to Erdal follow Chinese models. As such, Yarkand Old Uyghur documents provide first-hand evidence of the penetration of Arabic legal terms, formats and formulae into the legal practice of the Eastern Qarakhanid Khanate.

It is fruitful to compare Yarkand Old Uyghur documents not only with Arabic but also with Persian language land sale deeds from medieval Afghanistan. As will become clear below, such a comparison provides additional evidence for the spread of common Arabic-language substrate of legal practices to the Islamicate East, while also allowing us to observe how these traditions were adapted and localised.

A comparison of an Old Uyghur vs. a Persian land sale deed

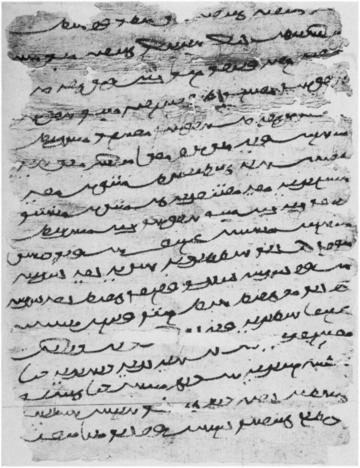

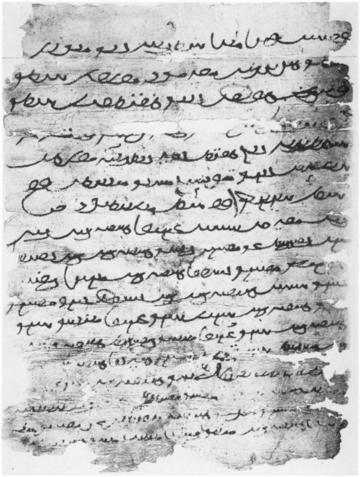

For this comparison, I have selected a Yarkand Old Uyghur document, edited and translated by Erdal (1984, pp. 269-77, document I, plates I, II: Turki 4 and Turki 5) and a Persian language document, Afghanistan National Archives, Firuzkuh 6 (unpublished edition and translation available online through the Invisible East programme).

Photographs Turki 4 and Turki 5 (Figure 1) show the recto and verso of this Old Uyghur document recording a sale of a piece of land in Rabul, a village near Yarkand. Written in 473 AH / 1080 CE, this is one of the oldest extant legal documents in a Turkic language. The document is written in neat lines on the recto and verso of the folio.

Figure 1. Turki 4 (left, recto) & Turki 5 (right, verso); photographed in 1910s by Sir Denison Ross; images after Erdal (1984, plates I, II).

Line 8 of Turki 4 contains a key word of Arabic origin: iqrār. In translation, it means ‘acknowledgement’, but the word has legal connotations. An iqrār was considered a voluntary declaration, made by the declarant (muqirr), in favour of a beneficiary (al-muqarr lahu) concerning an object of recognition (al-muqarr bihi). Legal documents using iqrār formats are known to have existed in the Bamiyan area (see Map 1) as early as the beginning of the 11th century. Their appearance in the Tarim Basin is indicative of the influence of Islamic legal practice and bureaucracy much further east.

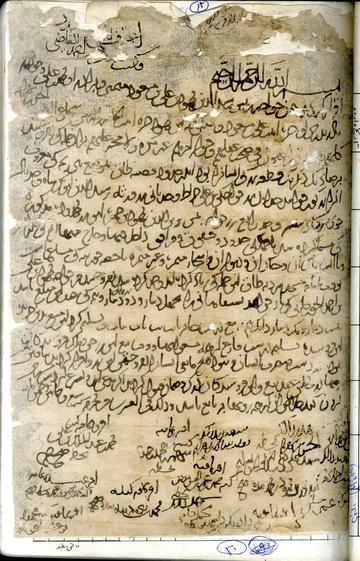

My comparandum, Afghanistan National Archives, Firuzkuh 6, is a land sale document written in New Persian. It is in a better physical condition than its Old Uyghur counterpart above. It acknowledges (the term used is again iqrār) the sale of a plot of land near a village called Ṭāq in 587 AH/ 1191 CE (Firuzkuh is shown as Ghur on Map 1; Ṭāq’s location remains unidentified).

Figure 2. Afghanistan National Archives, Firuzkuh 6, image courtesy of Nabi Saqee

The structure of iqrār documents

Iqrār contracts are very common among Islamic legal documents and they follow a common structural format. Here I adopt Geoffrey Khan’s analysis of such a structure (which he developed based on texts from the Cambridge Genizah collections), along with Ofir Haim’s structural amendments for contracts concerning land (which he used for texts from the Bamiyan Papers); I have made minor modifications and taken the more relevant aspects of their more comprehensive list. As per this structure, we expect to see the following clauses, with attention to the order in which they appear:

-

The basmala

-

Opening formula (where the iqrār is announced)

-

Identification of the muqirr (here, the seller)

-

Confirmation of the muqirr’s legal capacity

-

Object of recognition (muqarr bihi/lahu, here the land sale)

a. Name of buyer

b. Location and boundaries of land for sale

c. Price of sale and half that figure (to avoid illegal alteration of the document)

d. Confirmation that the seller has received the agreed sum

e. Muqirr renounces all claims on the sold property

-

Acceptance formula

-

Confirmation of witness statements

-

Date

-

Witness clauses

To determine if the same structure is also followed in the Old Uyghur and the Persian land sale deeds, I have provided an English translation of both documents side-by-side, where I have fitted each clause into its own cell (I have inserted several clauses in their own rows to better represent the similarity between the documents). Next to each I have noted how the clause compares to the structure suggested by Khan and Haim. To do this I insert the number referring to the list above.

|

Common iqrār structure |

Firuzkuh 6 (Trans. from Haim et al. on Invisible East Digital Corpus) |

Turki 4-5 (Trans. from Erdal 1984) |

Common iqrār structure |

|

1 |

[+ 1] b. Aḥmad the qāḍī acknowledged [+/- 2] and wrote [it]. In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate. |

(Lines may be missing) |

|

|

|

|

The names of the witnesses have been noted at the lower part of this document. The witnesses give conscious testimony. |

7 |

|

2, 3 |

The khwāja raʾīs Rashīd al-Dīn Maḥmūd b. ʿAlī b. Masʿūd Maymanī, his brother Muḥammad b. ʿAlī, his full sister, the noble woman, the daughter of ʿAlī b. Masʿūd, and the wife of this Maḥmūd, the noble woman, the daughter of the amīr and raʾīs Shujāʿ al-Dīn al-Ḥasan b. Bahrām, acknowledged, |

I, commander Bäk Tüzün's son, the veteran commander ʿAlī (and) I, commander Bäk Tüzün's son Aḥmad Arslan, |

2 |

|

4 |

all of them with their consent and of their own volition, of sound mind, legally capable of conducting their affairs, without coercion or force, the following: |

we two, being clear of mind, free of illness and sound of body, our mental powers being unimpaired, acknowledge: |

4, 3 |

|

5b, 5a |

They sold, in mutual agreement, a plot of land which they possess in the environs of the village of Ṭāq, in a place [+/- 2] known as Zamīn-i Gūr. The first boundary is the land of Khwājagī b. ʿAlī the turner. The second boundary is the land of the heirs of Rashīd al-Dīn Abū Bakr Shāh. The third boundary is the canal of the partners of [+ 1]. The fourth boundary is the land of the khwāja raʾīs Zayn al-Dīn Maḥmūd b. Ḥamza. This delimited and mentioned land which has been designated has been sold, with all the boundaries, rights and contents, interiors and exteriors, what is within it and what comes with it: its vines, its earth, its walls, its trees - fruit-bearing and barren - until the nut [+ 1] tree area, which is indivisible, (and) the waqf [land administered by] the imām of the mosque at the beginning of the village of Ṭāq. They sold all of what has been mentioned and delineated to khwāja Maḥmūd b. ʿAlī b. Aḥmad al-Jūzjānī, also known as [+1]-miyānī, |

I, commander ʿAli (and) I, Aḥmad Arslan have sold Master Isḥaq a piece of land in Rabul |

5a, 5b

(5b appears again below to delineate the property’s boundaries) |

|

5c |

for 42 and a half Mālikī gold dīnārs, half of this sum is 21 dīnārs and one-and-a-half dāng. [It is] a proper, lawful, effective, valid, absolutely definitive. |

for 800 yarmaqs. The half of this amount is 400 yarmaqs. We have sold this land, with its four boundaries, [to] Master Isḥaq. There will, after us, be no litigation or legal trick by our sons, our daughters, our wives, our family or by anybody. Whoever, not being satisfied, starts litigation, (that) is null and his witnesses are false. |

5c, 5e |

|

|

|

The first [boundary] of this land is the land which Buġra bäg sold; the second boundary is the mill-race; the third boundary is the land of B. tuδun; the fourth boundary is Buġra ögä's (?) [land. |

5b (The boundaries are detailed here) |

|

5d |

This seller handed over this object of sale to the buyer in a proper handover free of burdens [made by any claimants]. At the time of sale, this land was the rightful property of the seller's and it was at their disposal and use. There was no obstacle to the sale of this land. They acknowledged the receipt of the full amount at the meeting concluding the sale contract. |

|

|

|

5e |

These sellers confirmed the guarantee against defects. If a claimant comes forward and legally revokes the buyer’s access, the resolution of all aspects of this [dispute] rests with the seller. |

||

|

8 |

This [was written] on the 20th of Muḥarram in the year 587. |

In the year 473, in a mouse year, in the month of rabiʿ al-āḫir, this document was drawn up. |

8 |

|

9 |

[witnesses] |

[witnesses] |

9 |

Results of the comparison

The table shows that the two documents closely resemble one another. The similarities are not simply because both are land sales, but rather due to the order of appearance of their clauses. To make the comparison easier, I have shown the layout order without the translations in a more concise table below.

|

Firuzkuh 6 |

1 |

|

2,3 |

4 |

5b, 5a |

5c |

|

5d |

5e |

8 |

9 |

|

Turki 4-5 |

|

7 |

2 |

4, 3 |

5a, 5b |

5c, 5e |

5b |

|

|

8 |

9 |

The body of the documents follows a very similar order and layout. Both texts have the iqrār formula (2), followed by the identification of the seller (3) and a verification of their legal capacity (4). The object of acknowledgement (5) appears with its subsections in both documents, with some complications that are discussed in greater detail below. Both documents omit the acceptance formula (6). The date (8) and witness statements (9) appear in the same position, but the date in the Old Uyghur document includes not only the Hijri year and month (the day is omitted) but also the Sino-Turkic animal year. The Persian text mentions the full Hijri date of the contract. Both documents follow the structure of Arabic-language iqrār documents as established by Khan and the described similarities between them must stem from their common origins in the Arabic-language legal tradition.

Despite this, the documents’ format is not identical. Thus, the order of the elements in the description of the sale (5) is somewhat different in the two texts. Most notably, in the Old Uyghur document, point 5b is split, so that the location and boundaries of the plot are mentioned in two separate parts of the document. This format of the split 5b clause recurs in Turki 3: another Old Uyghur text from the collection.

The greatest difference between the Old Uyghur and the Persian documents is found in the introductory sections. Firuzkuh 6 starts with a basmala. This is, of course, the case in most Islamic texts, including the Arabic texts from the same collection published by Gronke (1986). Whether this was also the case in Old Uyghur texts in the corpus is unclear. All Old Uyghur texts from Yarkand, including Turki 4 (Figure 1), are damaged in such a way that the top section – and the would be basmala – is missing. The only complete Old Uyghur document from this collection is Erdal’s document VI (the Old Uyghur document in Arabic script). This document begins with a basmala. However, even its photograph is lost, and the document survives only as a 1942 transcript (Erdal 1984, p. 291 and plate VII) – not the most favourable piece of evidence. Erdal and Gronke conclude on this basis that Yarkand Old Uyghur documents display no religious affiliation. The present study finds this argument unsubstantiated due to lack of evidence.

After the basmala, Firuzkuh 6 starts with the iqrār opening formula (2). In contrast, the Turki document starts by confirming the validity of the witnesses (7). Erdal points out that other Old Uyghur documents from the collection open in the same way. Erdal and Gronke are agreed that non-Islamic Old Uyghur documents, influenced vastly by Chinese models, do not begin in this way either – those documents begin with the date. Further study is required to understand where this commonality among the Old Uyghur Yarkand documents stems from. The opening style of Old Uyghur Yarkand documents does, however, suggest that the Qarakhanid practice of writing legal documents outside the Chinese format was not borrowed wholemeal from the Islamic world. Instead, the Islamic models were adopted as a standard, but not an exact template.

Conclusions

It is striking that legal documents written not only in Persian but also in Old Uyghur reflect so much of the Arabic-language substrate of legal terminology, format and style. The Yarkand land sale documents therefore are testament to the legacy of Islamic law beyond the eastern boundaries of Afghanistan before the Mongol conquests. However, Old Uyghur land sale documents also diverge in places from their Arabic- and Persian-language counterparts, furnishing evidence for the adaptation and localisation of legal traditions in different parts of the Islamicate world.

Amat, Akbar, Arienne Dwyer, G. Eziz, Papas Alexandre, and C.M. Sperberg-McQueen. ‘Chagatay Manuscripts Transcription Handbook’. Chaghatay 2.0, 3 June 2018. https://uyghur.linguistics.indiana.edu/manuals/ManuscriptsTranscription.xhtml#Perso-Arabic_scripts.

Biran, Michal. ‘Ilak-Khanids’. In Encyclopædia Iranica, Online Edition. New York, 2012. https://iranicaonline.org/articles/ilak-khanids.

———. ‘Karakhanid Khanate’. In The Encyclopedia of Empire, edited by Nigel Dalziel and John M MacKenzie, 1–2. Wiley, 11 January 2016. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118455074.wbeoe156.

Bosworth, C. E. ‘Ilek-K̲h̲āns or Ḳarak̲h̲ānids’. In Encyclopaedia of Islam New Edition Online (EI-2 English), edited by P. Bearman. Brill, 2012. https://referenceworks.brill.com/doi/10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0360.

Duturaeva, Dilnoza. Qarakhanid Roads to China: A History of Sino-Turkic Relations. Handbook of Oriental Studies 8: Uralic and Central Asian Studies 28. Leiden: Brill, 2022.

Erdal, Marcel. ‘The Turkish Yarkand Documents’. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 47, no. 2 (1984): 260–301.

Khan, Geoffrey. Arabic Legal and Administrative Documents in the Cambridge Genizah Collections. Cambridge University Library Genizah Series 10. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Golden, Peter B. ‘The Karakhanids and Early Islam’. In The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, edited by Denis Sinor, 343–70. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Gronke, Monika. ‘The Arabic Yārkand Documents’. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 49, no. 3 (1986): 454–507.

Haim, Ofir. ‘Acknowledgment Deeds (Iqrārs) in Early New Persian from the Area of Bāmiyān (395–430 AH /1005–1039 CE)’. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 29, no. 3 (July 2019): 415–46. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1356186318000718.

Huart, Clément. ‘Trois Actes Notariés Arabes de Yârkend : Documents de l’Asie Centrale (Mission Pelliot)’. Extrait Du Journal Asiatique, 11, 4, no. 2 (1914): 607–927.

Pakatchi, Ahmad, Manouchehr Pezeshk, Sadegh Sajjadi, Esmaeil Shams, and Enayatollah Majidi. ‘ایلک خانیان (قراخانیان یا آل افراسیاب) [Ilak Khānids (Qara Khānids or Āl-i Afrāsiyāb)]’. In دنبالهٔ حکومتهای شرقی حکومتهای شمال و غرب ایران [Continuation of Eastern Governments: governments of north and western Iran], edited by Sadegh Sajjadi, 4–69. تاریخ جامع ایران [The Comprehensive History of Iran] 7. Tehran: مرکز دائرة المعارف بزرگ اسلامی, 2015.

Cite this article

Arghandehpour, M. 2025. “How to 'Acknowledge' a Land Dale in Old Uyghur: an Iqrār Document from Qarakhanid Yarkand.” Document of the Month. Invisible East. doi: 10.5287/ora-yre9e4y7g.

About the author

Mateen Arghandehpour is Digitisation Officer with the Invisible East Programme. He received his PhD from UCL in 2024, and his thesis considered how Persians attempted to manipulate the Greek states by means of their religious culture during the Greek-Persian Wars of the 5th century BC. His work deals mainly with historiography and intercultural interaction. He is interested in ancient languages, cultures and religions.

The online series, Document of the Month, presents some of the most interesting and revealing medieval documents from the desks of Invisible East researchers and their colleagues worldwide. Each piece in the series is dedicated to a single document or a closely related group of documents from the Islamicate East and tells their story in an engaging and accessible way. You will also find images, editions and translations of the documents. If you would like to contribute to the Document of the Month series, please, get in touch with Nadia Vidro.