Document of the Month 3/25: A Female Farmer with a Strong Voice

Divided Fields, Unbroken Will:

A Female Farmer's Stand in Medieval Afghanistan

by Arezou Azad

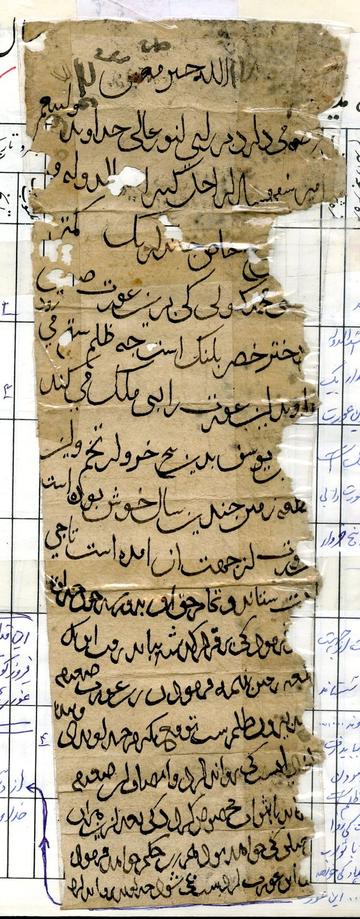

A female farmer's petition (Firuzkuh 95)

Firuzkuh 95 is a nondescript sheet of paper, in fact, a mere fragment. It was found ca. 30 years ago in the Firuzkuh area of Ghur, Afghanistan, together with some 100 other folios. The date hasn’t survived, but judging from the other (dated) documents in the Firuzkuh corpus that the Invisible East team has been reading, translating and digitising, we believe it was written in the 1170s, 80s or 90s; in other words, some 850 years ago.

What has been identified as a petition letter was written in Persian on behalf of a woman who was working as a tenant farmer. She is identified by her patronymic as “the daughter of Khiḍr b. Palang.” Since we do not know her given name, I’ve called her “Maryam” for convenience’s sake. Maryam has addressed her letter to a certain Asad al-Dawla wal-Dīn. Maryam and other peasants would petition Asad al-Dawla asking him to use his good offices to solve their problems. Asad al-Dawla seems to have been managing her plot. She addresses him with the military titles of amir (commander) and sifahsalar (commander-in-chief, or general), and also as a special [attaché?] (khāṣṣ) to a certain prince (bek) called Jāndār (lit., “life-having”). Asad al-Dawla was clearly an important man and was most probably responsible for a much larger area of land allocated to him as a military grant (iqṭāʿ ) by the Ghurid sultan for his services to the court. Iqṭāʿs were common forms of payment for military service by the neighbouring Seljuq state as well, and required the holder to administer financial transactions with the peasants around revenues, rent payments and taxes to generate income for themselves. For a more detailed discussion, see my forthcoming book, The Warehouse of Bamiyan: Economic Life in Medieval Afghanistan (Edinburgh University Press, 2025)

Fig. 1: Afghanistan National Archives, Firuzkuh 95 (image courtesy of Nabi Saqee). Full details of the document can be found in the Invisible East Digital Corpus.

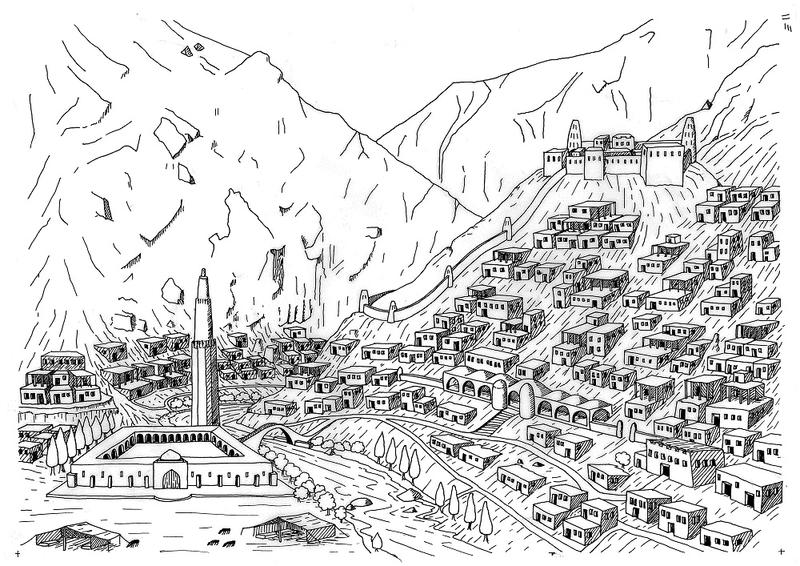

To give us some context, 850 years ago, Firuzkuh was part of the medieval region of Khurasan. It was an important administrative centre as the summer capital of the powerful sultan of the vast Ghurid Empire, which at its largest extent in the mid-12th century included parts of Iran, Afghanistan, Central Asia and India (an area ca. five times the size of the UK). The main ruin that survives today from that sumptuous capital is the Minaret of Jam, a UNESCO heritage site (currently in a precarious state of preservation). Our petition is coming not from the city of Firuzkuh but from a rural farm in its periphery.

Fig. 2: Minaret of Jam. By David Adamec - Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12624288

Fig. 3: Hypothetical reconstruction of Ghurid Firuzkuh in a line drawing by Catriona Bonfiglioli. First published in David C. Thomas, The Ebb and Flow of the Ghurid Empire, Figure 5:59. Reproduced by permission from Catriona Bonfiglioli and David Thomas.

Pause for thought: the life of female farmers in medieval Khurasan meets with silence in our traditional sources (chronicles, biographical compilations, etc), and the information in this document gives us an exceedingly rare insight into the realities faced by medieval female farmers. It allows us to test assumptions about agency and self-perceptions of women in medieval Afghanistan, and of the peasant communities in medieval societies at large.

Maryam’s agency and self-perception

What case is Maryam making in her letter? After the usual words of flattery reserved for senior recipients of letters who are several tiers above the sender’s level, Maryam spells out her problem. Her landlord, the addressee, has notified her that he will strip her of half the land she has been apportioned! He must have communicated this to her previously, either verbally or in a letter which hasn’t survived in the corpus. Apparently, he has told her that he will transfer that half to a certain Yūsuf.

The reason for this drastic 50 percent cut and massive impact on Maryam’s income appears to be something that happened with five donkey-loads of seed. The details are not given in the petition. Perhaps she defaulted in her in-kind rental payment, or some other form of financial transaction, such as a loan or a tax payment that amounted to five donkey-loads of seed (which is not a small amount and points to a decently-sized plot that she was cultivating).

Or perhaps Asad al-Dawla had provided a state grant or subvention of that amount of seed to her, with the expectation that she produce a certain level of yield which she, unfortunately, hasn’t met. We don’t know why. Perhaps there were family or climate conditions that prevented a good harvest. All of these scenarios are entirely possible as we have identified them in other documents of the corpus with regard to other peasants. For example, the Bamiyan corpus attests to seed advances issued by the state. The state monitored their effective use, presumably to ensure recouping its outlay, and ideally, to make profitable returns. We also have plenty of legal documents (written in the iqrār format) in the corpora from Firuzkuh and Bamiyan in which peasants commit themselves to paying back loans, and to the possibility of having to pay bruising fines in case they default on their repayments.

Whatever the reason, Maryam argues that the penalty is unjust, given her history of keeping her “plot productive for several years now.” She feels robbed of her rights and requests her entitlement to be fully restored. She appeals to the landholder’s conscience by reminding him that,

“the expectation from the master [who is meant to be] benevolent and kind to [his] servants, is that he does not unjustly deprive this poor [woman] of her justice. [In this way,] he will be worthy of recompense [in the next world] since after doing so, every [case?] like this, will be dealt with in accordance with this order.”

Maryam’s tone is confident and assertive. She has taken the time to petition and make her case, rather than acquiescing quietly to what appeared to her as a sudden and unjust decision by the landlord. It is not clear what she suggested for remedying the situation. Perhaps she negotiated a new repayment schedule. We simply do not know since the end of the document hasn’t survived. Or, if the petition continues on the verso side, we can’t read it since the document has (disastrously!) been stuck onto a notebook by its owner 30 years ago obscuring the back of the sheet. It is now in the Afghanistan National Archives which we have not been able to visit (we are working off of high-resolution photos acquired by Nabi Saqee, a native of Ghur province and author of the first book on the documents; on the discovery and modern preservation of the Firuzkuh Papers, see this video made by Invisible East).

Hiring a scribe to present her case “in the prescribed way”

Maryam’s letter is not written in the first person. Instead, she has hired a scribe to write in her name. Whether or not she herself was literate, hiring a scribe ensured that her letter complied with the standard protocol of letter-writing.

The scribe identifies himself on the first line of the petition as “the lowly Mūsā b. Muḥammad Kūlī”: self-deprecation and deference towards a senior recipient is a must, according to the 12th-century Persian letter-writing manual by Muḥammad b. ʿAbd al‑Khāliq Mīhanī, Āyīn- dabīrī.

Mūsā (Moses) never addresses the recipient in the second person. Surely, that would be too forthright and direct and would constitute a breach of protocol. Perhaps the scribe was known to the rural peasantry and farming community and specialised in writing petitions on their behalf. We can see from his accurate orthography and close alignment with petition-writing formats spelled out in administrative manuals, that Mūsā was a pro (or a good imitator of pros)! Either way, Maryam would have paid him for his services: an expense she would have considered worth incurring.

We can guess from comparanda how Maryam’s letter must have continued if the full text were visible. One petition to the Fatimid female ruler of Egypt, Sitt al-Mulk, dated from a century and a half earlier to the 410/1020s, is spelled out by Marina Rustow (“The Fatimid Petition,” 370-1); building on Geoffrey Khan, “The Historical Development of the Structure of Medieval Arabic Petitions”. The structure aligns closely with Maryam’s petition in Firuzkuh 95:

-

Name of sender (tarjama)

-

Opening blessings (ṣalwala)

-

Presentation of problem (matn, baʿdiyya, narratio)

-

Request (qiṣṣa or ruqʾa)

-

Arenga (“softens the request while flattering the recipient”)

-

Dispositio/raʾy clause

-

Closing blessing (ḥamdala, taṣliyya).

Maryam’s fragment is missing points 5-7.

Conclusion

We will never know the outcome of Maryam’s case. The lord would have been sure to respond; but if he did, his letter hasn’t survived.

What we do know now is that Maryam was a medieval farmer; a business woman. She understood her rights and channels for redress, and utilised them. We also know that she was working hard to succeed, possibly managing junior peasant workers on her medium-sized plot.

And so, we celebrate and recognise Maryam’s agency, confidence and hard work today on International Women’s Day: 850 years after the fact. It is always better late than never. Congratulations Maryam and all hard-working female farmers around the world today and in times past.

Afghanistan National Archives, Firuzkuh 95, O. Haim, N. Saqee and A. Azad, unpublished transcription and translation available online through the Invisible East programme.

- الله خیر معین

- عرضه می دارد بر رای انور عالی خداوند ولینعم

- امیر سفهسالار اجل کبیر ا[سد] الدوله و

- [الدین الـ]ـغ خاص جاندار بک کمتر

- [مو]سی محمد کولی کی برین عورت ضـ[ـعیـ]ـف

- [کی] دختر خضر پلنگ است چه ظلم ستم می رود

- [خـ]ـداوند این عورت را بی ملک می کند

- [+ 1] یوسف بدین پنج خروار تخم و این

- قطعه زمین چندین سال خوش بوده است

- [ایـ]ـن عورت از جهت آن آمده است تا چی

- [+ 1] ستاند و تمام حق او بدو رسد چون خداوند

- [+ 1] فرمود کی بر قرار گذشته بباید رفت این یک

- [قطـ]ـعه زمین نیمه فرمودن برین عورت ضعیفه

- [از] حد بیرون ظلم است توقع بکرم خداوندی و بنده

- [نو]ازی اینست کی روا ندارد و انصاف این ضعیفه

- [سـ]ـتاند تا بثواب مخصوص گردد کی بعد ازین هران

- [+ 1] چنان کی خواهد بود همبرین حکم خواهد فرموده

- [آیـ]ـد این عورت از دست بمی شود خداوند روا ندارد

Afghanistan National Archives, Firuzkuh 95, O. Haim, N. Saqee and A. Azad, unpublished transcription and translation available online through the Invisible East programme.

-

God is the best helper.

-

The lowly Mūsā(?) b. Muḥammad Kūlī petitions for enlightened and superior judgement by the beneficent lord,

-

the illustrious and grand amīr and sifāhsālār, Asad(?) al-Dawla

-

[wal-Dīn Ulu]gh khāṣṣ jāndār bek,

-

on: the injustice that is being committed against this poor woman,

-

the daughter of Khiḍṛ b. Palang.

-

The master is dispossessing this woman of her land

-

[in favour of?] Yūsuf because of(?) these 5 donkey-loads of seed. This

-

plot of land has been productive for several years now.

-

This woman has come [here] for this reason so that she

-

retains what [is her due?] and that all her rights are fully restored. By

-

[+1] ordering that the previous practice be followed and this

-

plot of land be divided in two, the master is subjecting this poor woman

-

to excessive injustice. The expectation from the master [who is meant to be] benevolent and

-

kind to [his] servants, is that he does not unjustly

-

deprive this poor [woman] of her justice. [In this way,] he will be worthy of recompense [in the next world] since after doing so, every

-

[case?] like this, will be dealt with in accordance with this order.

-

It would not be appropriate for the master to deprive this woman.

Primary Sources

Mīhanī, ʿAbd al-Khāliq. Āyīn‑i dabīrī. Edited by Akbar Naḥwī. Tehran: Markaz‑i Nashr‑i Dānishgāhī, 1389/2010–11.

Secondary Sources

Azad, Arezou, with Pejman Firoozbakhsh, The Warehouse of Bamiyan: Economic Life in Medieval Afghanistan. Islamicate East: New Approaches to Texts and History Series. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press (forthcoming in 2025)

Haim, Ofir. “Acknowledgement Deeds (Iqrārs) in Early New Persian from the Area of Bamiyan (395–430 AH/1005–1039 CE)”. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 29, no. 3 (2019): 415–46.

Khan, Geoffrey. “The Historical Development of the Structure of Medieval Arabic Petitions”. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 53, no. 1 (1990): 8–30.

Muhammad, Khwaja, and Nabi Saqee. Barg-hā-ī az yak faṣl ya asnād-i tārīkhī-yi Ghur. Kabul: Intishārāt-i Saʿīd, 1388/2009.

Rustow, Marina. “The Fatimid Petition”. Jewish History 32, no. 2/4 (2019): 351–72.

Saqee, Nabi. “Fīrūzkūh Papers: Pre-Mongol Persian Documents from Today’s Afghanistan”. Invisible East blog, November 2024.

Thomas, David C. The Ebb and Flow of the Ghurid Empire. Sydney: Sydney University Press, 2018.

Cite this article

Azad, A. 2025. “Divided Fields, Unbroken Will: a Female Farmer's Stand in Medieval Afghanistan.” Document of the Month. Invisible East. doi: 10.5287/ora-kz8k4kka6.

About the author

Arezou is a historian of the medieval Islamicate East from the coming of Islam in the 7th century CE to the Mongol Empire of the 13th century, and all its various component cultures and societies. She is Programme Director of Invisible East, Senior Research Fellow at the Department of Continuing Education, University of Oxford, and Lauréate de la Chaire et Professeur junior, Institut national de civilisations orientales (Inalco), Paris

The online series, Document of the Month, presents some of the most interesting and revealing medieval documents from the desks of Invisible East researchers and their colleagues worldwide. Each piece in the series is dedicated to a single document or a closely related group of documents from the Islamicate East and tells their story in an engaging and accessible way. You will also find images, editions and translations of the documents. If you would like to contribute to the Document of the Month series, please, get in touch with Nadia Vidro.