Document of the Month 7/25: Invisible East Qur’ans

Fragments from Once-Complete Qur’ans

by Alya Karame

This essay is about Qur’anic fragments in the Invisible East corpus that are hundreds of years old. The first questions that come to mind when one looks at such historical documents are: What happened to them? Who made them? Who commissioned them? Who used them? And in whose hands did they fall? Almost like surgical specimens, these fragments can reveal the invisible. They tell us about the people that laid eyes on them, from the time they were copied until the present moment, when they are digitised to be read online.

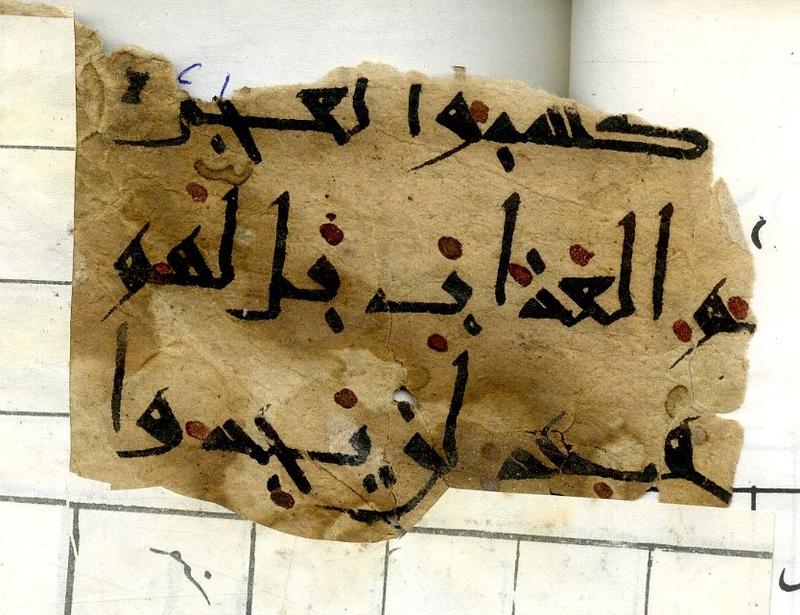

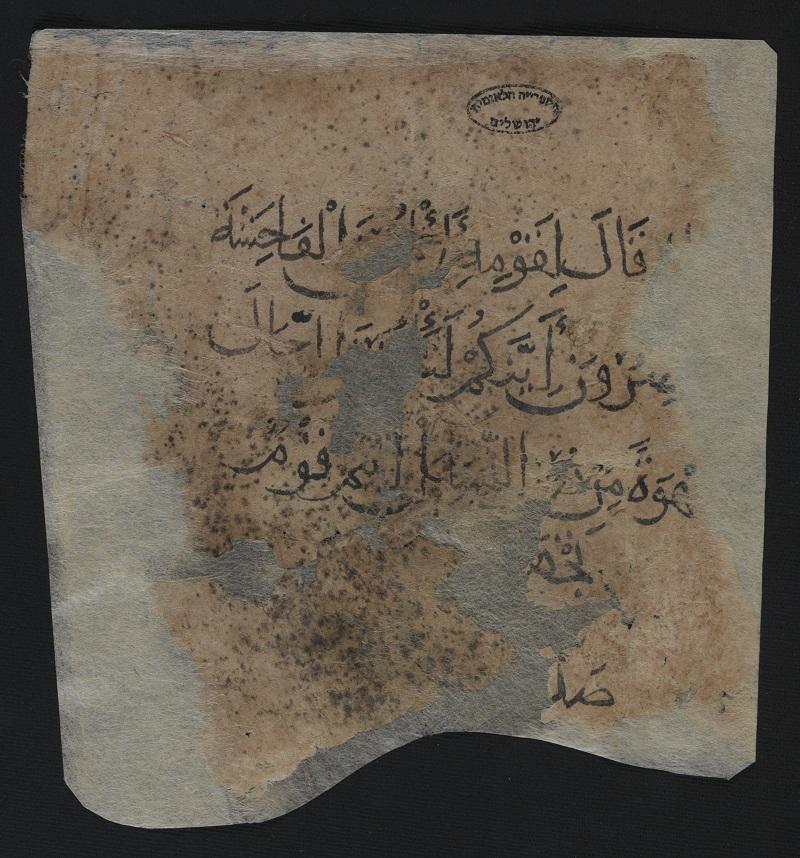

Fig. 1: Afghanistan National Archives, Firuzkuh 88 (left) and Firuzkuh 89 (right), showing the recto and verso of the same folio, pasted into a modern notebook (image courtesy of Nabi Saqee). Full details of the documents can be found in the Invisible East Digital Corpus here and here.

The fragments

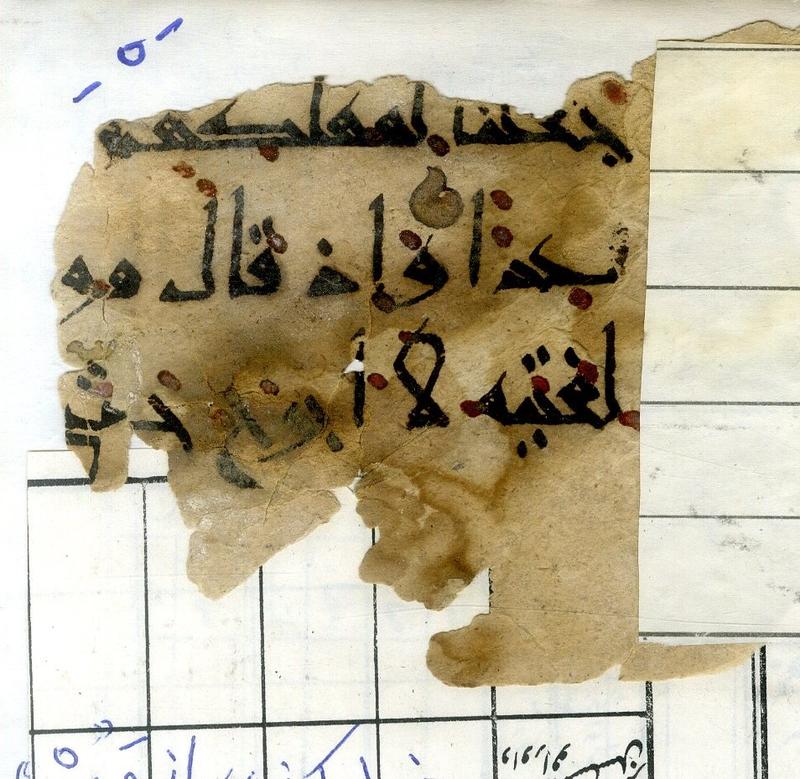

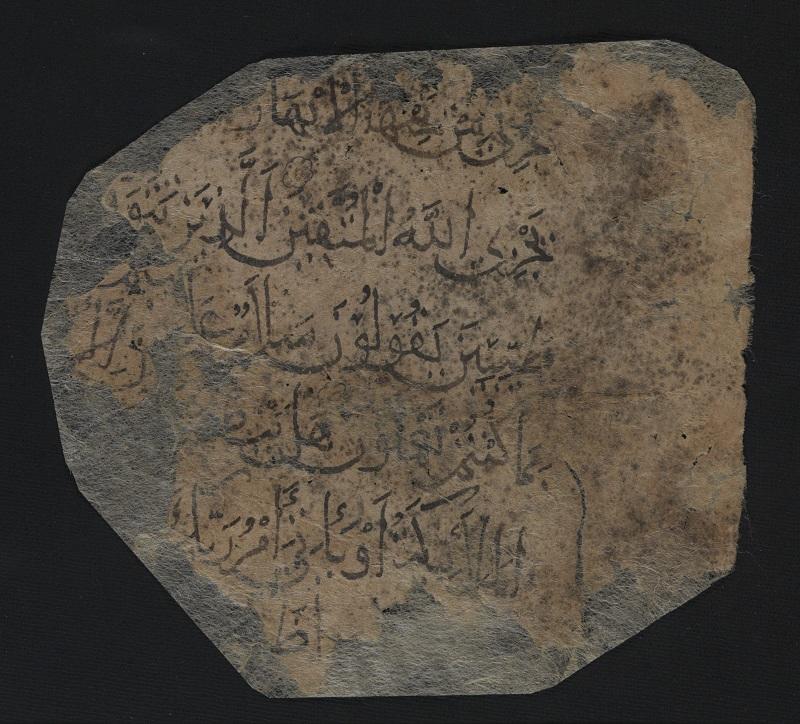

The five fragments discussed here come from two groups of manuscripts from modern-day Afghanistan, known as the Bamiyan Papers and the Firuzkuh Papers. Firuzkuh 88–89 (Figure 1) contains verses 58 to 60 from sūrat al-kahf (The Cage); Firuzkuh 90 (Figure 2) contains verses 90 and 91 from sūrat al-nisāʾ (The Women). These Qur’anic fragments, copied on paper, employ the same script called the ‘New Style’, generally characterised by triangular and trapezoidal heads of letters and diagonal descending strokes (bowls and tails). However, they are not from the same manuscript. The differences are clear: Notice how the script of Firuzkuh 88–89, with its straight diagonal strokes, appears more rigid than that of Firuzkuh 90, which exhibits more curvilinear strokes. These slight differences reflect the individual preferences of copyists who worked within the same scribal tradition. As scribes transmitted the sacred words of God, their agency was visible and can be detected in the aesthetic decisions they sometimes made. To give but one example: notice how the copyist of Firuzkuh 90 cut the final letters of the words at the end of the 5th and 6th lines on verso, turning them vertically – this was the solution they came up with for the miscalculated space as they reached the end of the line.

Fig. 2: Afghanistan National Archives, Firuzkuh 90, recto (left) and verso (right), pasted into a modern notebook (image courtesy of Nabi Saqee). Note the vertically written characters in lines 5 and 6 on verso. Full details of the document can be found in the Invisible East Digital Corpus

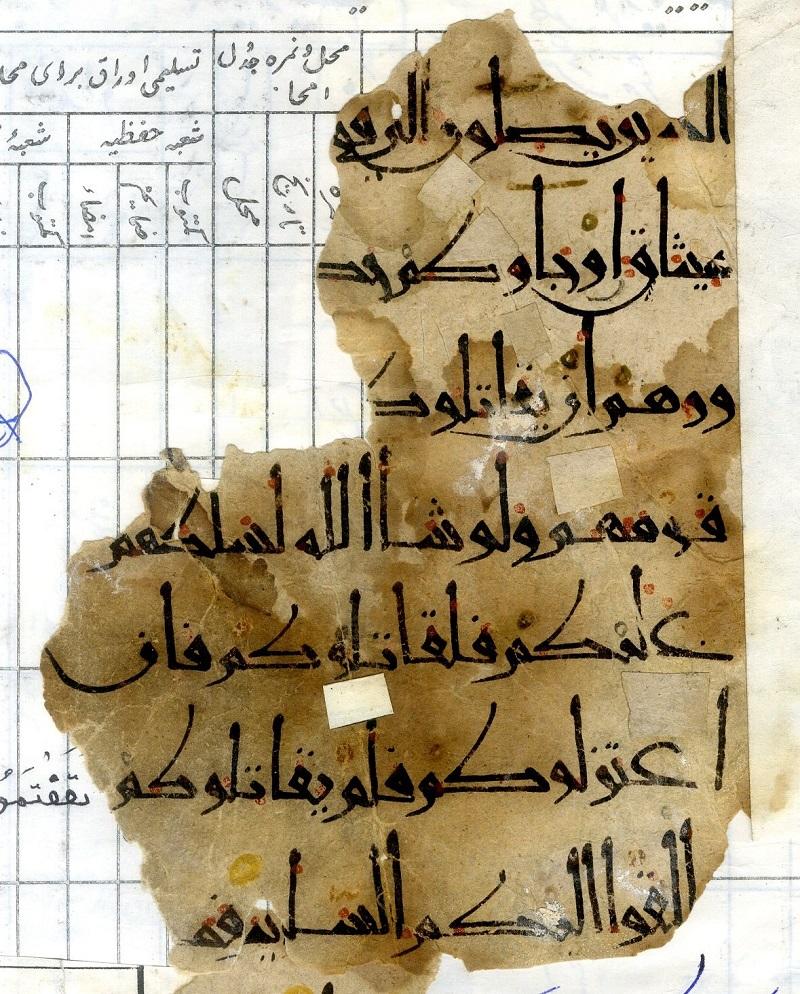

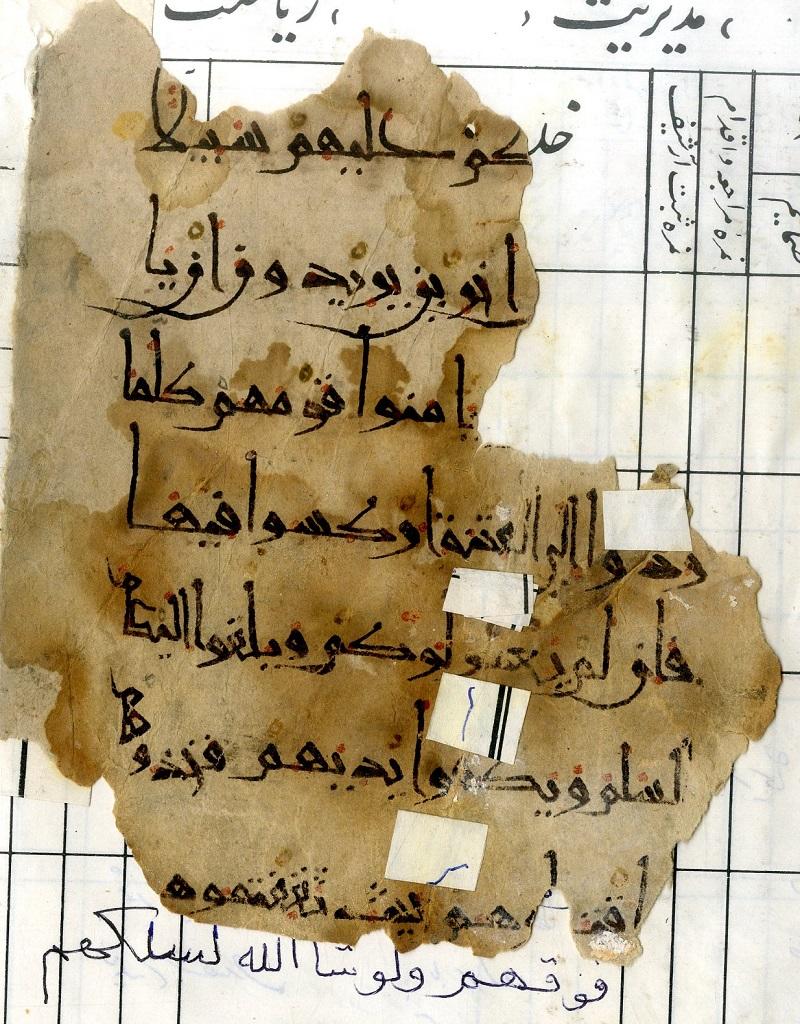

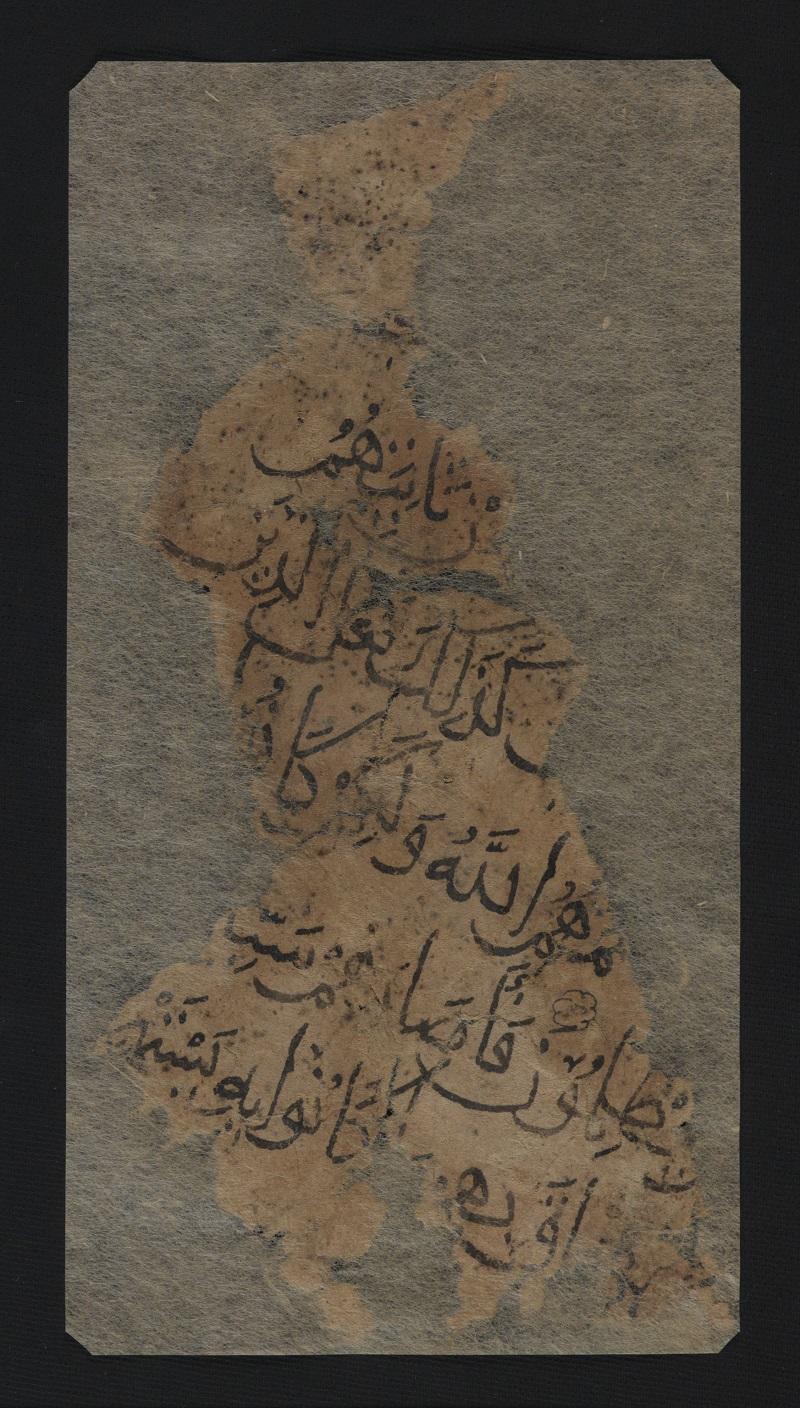

The Bamiyan fragments are copied in a different script, one I call the ‘Round Style’, a legible script that developed out of the book scripts and the everyday handwriting of the period to gradually gain consistency and proportions. NLI, Ms. Heb. 8333.180 (Figure 3) holds verses 54 and 55 from sūrat al-naml (The Ant). Both NLI, Ms. Heb. 8333.181 (Figure 4) and NLI, Ms. Heb. 8333.182 (Figure 6) contain verses from sūrat al-naḥl (The Bee), the former holding verses 28 through 33 and the latter verses 29 through 34. Is it a coincidence that what survives from two original Qur’ans has overlapping verses? Is it why they were preserved in the first place? The verses describe the condition of the soul after death, highlighting how believers go to heaven and disbelievers enter hell directly after death. We cannot be sure if this message had a personal meaning for the person that preserved them. However, visually speaking, all three Bamiyan fragments employ the same script and the same ink, suggesting that they are the work of a single copyist or perhaps of many copyists in a single workshop. We do not know whether they were at some point removed from complete Qur’ans, or, in the case of NLI, Ms. Heb. 8333.181 and NLI, Ms. Heb. 8333.182, were failed drafts of the same folio, but they were certainly produced by the same people.

Fig. 3: NLI, Ms. Heb. 8333.180, recto. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Israel. “Ktiv” Project.

Fig. 4: NLI, Ms. Heb. 8333.181, recto. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Israel. “Ktiv” Project.

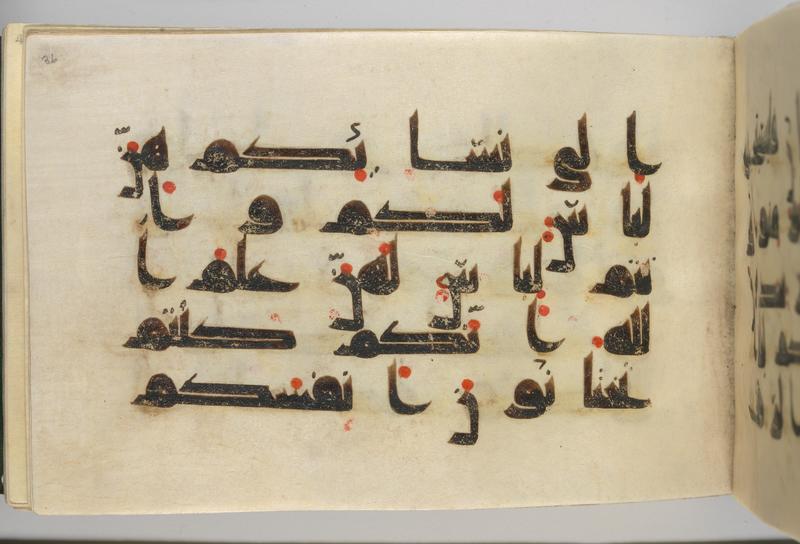

Based on their scripts, the Firuzkuh and Bamiyan Qur’anic fragments can be securely placed within a corpus of Qur’ans copied at the eastern frontiers of the Islamicate lands under the consecutive rules of the Ghaznavids (r. 366/976–582/1186) and Ghurids (r. 539/1144–612/1215). This eastern corpus stands at the beginning of a transformative phase in the history of the Qur’an manuscript when paper was gradually adopted as material support, displacing parchment; the vertical format replaced the horizontal one; and and Kufic script, which was employed throughout the Islamicate world from the 8th to the 10th centuries, was steadily abandoned for the new scripts (see Figure 5 for an example of an old style Qur’an). The visual identity of this eastern corpus synthesised transregional traits that can be loosely defined as Khurasani. Hence, the importance of the Bamiyan and Firuzkuh Qur’anic fragments stems from their being at geographic crossroads on the eastern frontiers of the Islamicate world, and at the same time, being representative of a turning point in the history of the Qur’an.

Fig. 5: Qur’an manuscript, late 9th–early 10th century. Metropolitan Museum of Art, object number 37.142. Gift of Philip Hofer, 1937. Public domain

The fragments’ use and role

The Firuzkuh fragments are vocalised using red dots: a dot above the letter represents a fatḥa, one below the letter a kasra, and a dot on the line a ḍamma. Other marks, such as sukūn and shadda, were added in what seems to have been green ink that contained iron, now oxidised (see Figures 1 and 2). This old system of vocalisation was used in the Kufic tradition (as seen in Figure 5). It was, however, replaced by the modern system seen in the Bamiyan fragments in which vowels are marked as we know them today in the same black ink as the main text (see Figures 3 and 4). This shift between the system of dots and the modern vowels once again places our fragments between the old and the new traditions.

The presence of vowels reminds us that our Qur’an fragments reflect only one of the many variant readings (qirāʾāt) in circulation. These variant readings followed different recitational schools that developed throughout the Islamicate world. Furthermore, the small rosettes seen in NLI, Heb. 8333.180r (Figure 3, line 2) and NLI, Heb. 8333.182v (Figure 6, line 2 from bottom) have a related role and mark ends of verses following the reading tradition chosen in the manuscript, since the division of verses can differ between readings. The rosettes may appear decorative at first, but they have a functional role in structuring the text and guiding its recitation. However, they may have been added later, after the copying of the text, because no space on the line had been conceived for them in advance. The marking of vowels and ends of verses indicates that the fragments were used and relied on for Qur’an recitation. Their original sizes, estimated from the surviving fragments, are also very telling of how they were used. At around 15 cm wide and no more than 20 cm high, these books were similar to the size of novels today. They must have been perfectly comfortable to hold in one’s hand and were certainly intended for individual use.

Fig. 6: NLI, Heb. 8333.182v. Notice a small rosette over line 2 from the bottom. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Israel. “Ktiv” Project.

In addition to their role as recitation guides, these fragments and the original manuscripts to which they once belonged bestowed blessing (baraka) on their patrons, and often reflected prestige. Even if paper was cheaper than parchment, commissioning a Qur’an was only possible for those who could afford it: the wealthy elite and ruling classes. Our fragments were, therefore, most likely commissioned for the private libraries of their patrons, either for their mosque or for their school. We do not know how much people were paid at the time for producing a Qur’an but we know that it was a time-consuming task that could take years to complete and could be accomplished only by those trained in beautiful calligraphy and illumination.

The afterlives

Found in a cave in the village of Shahr-i Khurū in today’s Afghanistan, the Firuzkuh Qur’anic fragments are part of what has become known as the Firuzkuh Papers, documents of mainly legal and administrative nature. They have been purchased from the locals by Mirza Khwaja Muhammad, who first published them in 2009 together with Nabi Saqee, currently a member of the Invisible East team. They were later donated to the Afghanistan National Archives, where they are still preserved today.

Fig. 7: Caves in Shahr-i Khurū, the find-spot of the Firuzkuh Papers

Unlike the Firuzkuh Papers, it is unclear how the Bamiyan Papers were originally discovered, but they were most likely found in the Bamiyan area and circulated in the hands of antiquities dealers and private collectors. Some of these documents were in Hebrew script and belonged to the archive of a Jewish family that lived in Bamiyan during the Ghaznavid period. As part of its project to collect materials related to Jewish history, the National Library of Israel purchased around 220 of these texts, first in 2013 and again in 2016. Although more than half of the NLI collection consists of 11th- to 13th-century administrative documents in Arabic and New Persian, and the collection also includes the Qur’anic fragments discussed here, it is now known as the “Afghan Geniza”. With no evidence that they were ever part of a geniza – usually a storage room for worn-out sacred texts in a synagogue – this designation flattens the cultural diversity that had once existed at the eastern frontiers of the Islamicate world.

The cities of Firuzkuh and Bamiyan were commercial centres that were well positioned on the so-called Silk Road. They were ruled by the Ghurids, from whom very few monuments survive to shed light on the mixed communities that once inhabited them. We add to them the Qur’ans discussed in this essay. Fragmentary, like most of the monuments they once complemented, these Qur’ans are interwoven with the stories of those who copied, commissioned and used them. As they remind us of the people behind them, they inform us of scribal practices, the ways in which the Qur’an was visually transmitted, and the roles that Qur’an manuscripts played in Muslim communities.

Déroche, François. The Abbasid Tradition: Qur’ans of the 8th to 10th Centuries AD. The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art 1. London: Nour Foundation, 1992.

Flood, Finbarr Barry. ‘Ghurid Monuments and Muslim Identities: Epigraphy and Exegesis in Twelfth-Century Afghanistan’. Indian Economic and Social History Review 42, no. 3 (2005): 263–94.

Karame, Alya. ‘Ghaznavid Imperial Qur’an Manuscripts: The Shaping of a Local Style’. In The Word Illuminated: Form and Function of Qur’anic Manuscripts from the Seventh to Seventeenth Centuries, edited by Simon Rettig and Sana Mirza. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Scholarly Press, 2023, 27–53. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.21948098

––––. The Forgotten Qur’ans of the Eastern Islamic World. Manuscripts of the Ghaznavid and Ghurid Dynasties, Eleventh–Twelfth Centuries CE. Edinburgh University Press, Forthcoming in 2026.

––––. ‘Les manuscrits coraniques à Nishapur au début du XIeme siècle'. In The Qur’an and its Handwritten Transmission, edited by François Déroche. Brill, 2024, 223–45.

Khwaja Muhammad and Nabi Saqee. Barghā-ī az yak faṣl ya asnād-i tārīkhī-yi Ghur. Kabul: [I]ntishārat-i Saʿīd, 1388/2009.

Richard, Francis, Noshad Rokni, Amir Mansuri and Behruz Amini. Report on the State of the National Archive of Afghanistan and Its Manuscript Collection. Kent, OH and College Park, ML: Kent State University School of Library and Information Science and Roshan Institute for Persian Studies, 2016; available at: https://persianmanuscriptinitiative.github.io/img/Report_on_the_State_of_the_National_Archive_of_Afghanistan_and_its_Manuscript_Collection_Revised_final.pdf

Rustow, Marina. The Lost Archive. Traces of a Caliphate in a Cairo Synagogue. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2020.

Cite this article

Karame, A. 2025. “Fragments from Once Complete Qur’Ans.” Document of the Month. Invisible East. doi: 10.5287/ora-o0npn8rx4.

About the author

Alya Karame specialises in Islamic art, with a focus on manuscripts. Her forthcoming book (Edinburgh University Press, 2026) is centred around an understudied corpus of Qur’ans from the eastern Islamicate lands, copied between the 10th and 12th centuries. Her research has been supported by numerous grants and fellowships. She is currently a research associate at the Orient-Institut Beirut.

The online series, Document of the Month, presents some of the most interesting and revealing medieval documents from the desks of Invisible East researchers and their colleagues worldwide. Each piece in the series is dedicated to a single document or a closely related group of documents from the Islamicate East and tells their story in an engaging and accessible way. You will also find images, editions and translations of the documents. If you would like to contribute to the Document of the Month series, please, get in touch with Nadia Vidro.