Nowruz in Balkh and Bamiyan

Nowruz in Balkh and Bamiyan

by Nabi Saqee, March 2025

Nowruz, “New Day”, marks the start of the Persian New Year and the beginning of spring. Celebrations begin on the first day of the month Farvardin, which coincides with the spring equinox, and last for forty days. This ancient, Zoroastrian festival survived the Islamic conquests of the 7th century CE and is today a major national and historical holiday in Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and several other countries.

In the greatest epic of Persian literature, the Shahnameh of Firdawsī (940–1019 or 1025 CE), Nowruz is linked to the coronation of Jamshid, the mythical king of Iran:

With his royal farr he constructed a throne studded with gems, and had demons raise him aloft from the earth into the heavens; there he sat on his throne like the sun shining in the sky. The world's creatures gathered in wonder about him and scattered jewels on him, and called this day the New Day, or No-Ruz. This was the first day of the month of Farvardin, at the beginning of the year, when Jamshid rested from his labors and put aside all rancor. [Translation by Dick Davis.]

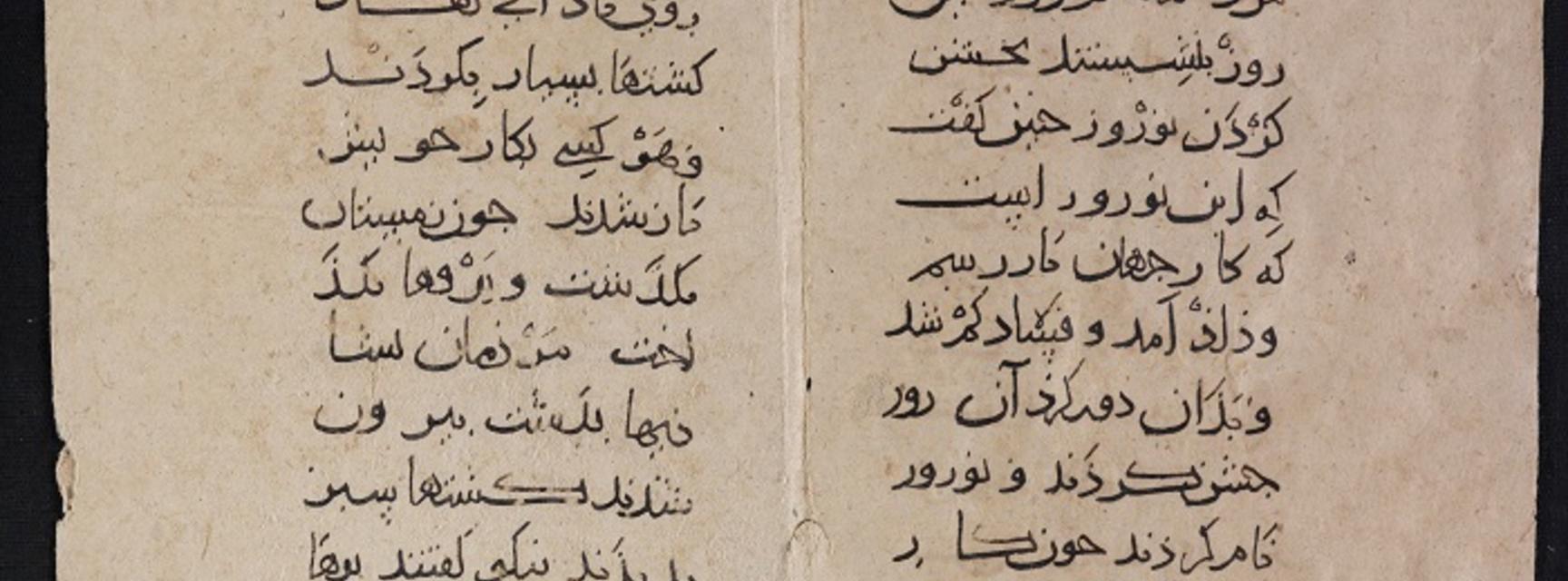

The same theme appears in the Bamiyan manuscript National Library of Israel, Ms.Heb.8333.188, a bifolio from a text on the kingdom of Jam (11th c.).

Figure 1: NLI Ms.Heb.8333.188 verso.

The text reads:

The kingdom returned to its rightful owner. On the first day of the month Farvardin1, they sat down to celebrate Nowruz. And he [Jamshid] said: This is a new day because the affairs of the world have returned to law and justice. They celebrated that day and called it Nowruz.

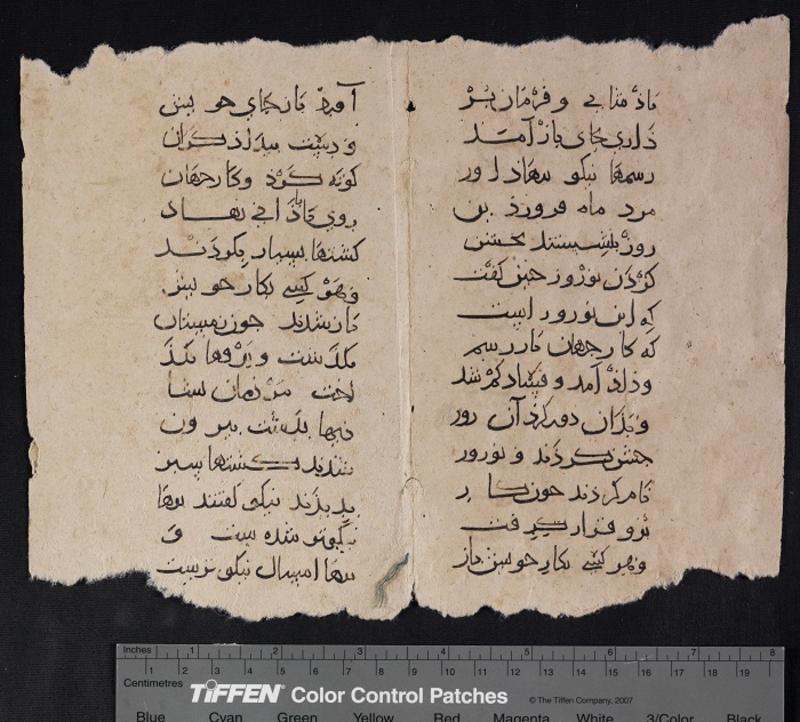

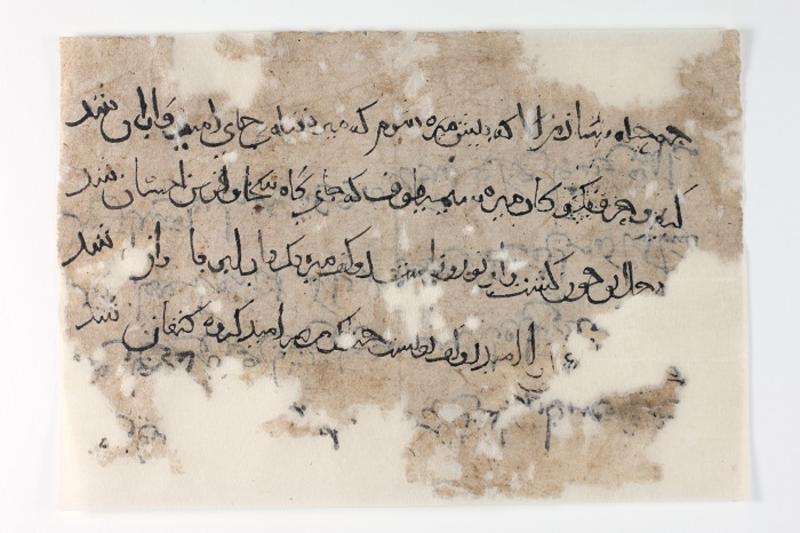

In the Bamiyan manuscript NLI Ms.Heb.8333.7, 9, 10, 14 the mention of Nowruz conjures up an entirely different and more familiar image of the beginning of spring. This damaged set of fragments preserves a panegyric to a Jewish notable in 11th-century Bamiyan, by the name Abū al-Ḥasan Siman Tov b. Abī Naṣr b. Dāniyāl. The unknown poet praises Siman Tov for his benevolence and generosity and asks him for money, wine, and fruit needed to entertain a large number of guests.

Figure 2: NLI Ms.Heb.8333.10 verso. Full details of the document can be found in the Invisible East Digital Corpus.

In NLI Ms.Heb.8333.10 the “open hand”, that is the generosity of “mira Sīmī-Tov”2 is said to give hope to the needy just as a rain-filled cloud helps a sown field sprout and turn green at Nowruz:

What can I do but to approach the mira / for the mira is the one to whom the hopeful turn.

The generous, noble and benevolent mira Sīmī-Tov / who has become the seat of mercy and the companion of beneficence.

[The heart?] of the people is like a sown field at new year / and the mira’s open hand is like a rain-filled cloud.

[Suffering?] has ceased [?] with the hope that your open hand brings / just like Egypt became the hope of the Canaanites.

[Translation by Arezou Azad, Nabi Saqee and Ofir Haim, revised from a publication by Olga Yastrebova]

Nowruz traditions in modern-day Afghanistan

Among the best-known traditions of Nowruz is the the Haft-Sīn (“seven S”) spread on which foods are displayed that start with the letter “S” (often alongside other symbolic items). These are:

-

Sīb (apples)

-

Samanū/samanak (sweet paste made of wheat)

-

Sabzah (sprouts)

-

Sīr (garlic)

-

Sirkah (vinegar)

-

Sinjid (oleaster)

-

Sumāq (sumac berries)

Figure 3: The Haft-Sīn table.

However, in Afghanistan, where the Bamiyan Papers are from, the central symbol of Nowruz is Haft-Mīwa (“seven fruits”), which is a dish made with raisins, walnuts, almonds, pistachios, apricots, hazelnuts, and oleaster. Other traditions are also prominent. Villagers paint their animals in bright colours and visit each other. In Mazar-i Sharif, the capital of the Balkh province, a flag is raised over the shrine of the caliph ʿAlī on Nowruz and is flown for forty days.

Figure 4: The shrine of the caliph ʿAlī in Mazar-i Sharif, Afghanistan.

Nowruz celebrations also coincide with the blooming of tulips in the fields and mountains of Balkh. This stunning spectacle gave rise to the Red Tulip Festival (Mīla-i Gul-i Surkh) in Mazar-i Sharif that draws crowds from all over Afghanistan.

Figure 5: In Balkh, red tulips are in bloom at Nowruz.

Today, as a thousand years ago when the anonymous poet wrote his panegyric to Siman Tov (literally, “a good sign”), blooming green fields at Nowruz are an evocative symbol of hope, anticipation and renewal.

Notes:

1 The scribe appears to have mistakenly swapped the day and the month.

2 Sīmī-Tov may be a scribal mistake for Siman Tov.

Attribution:

This blog's listing image "Haft Mewa compote" by Waleedkabul is licensed under CC BY 2.0. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Haft_Mewa_compote.jpg

Azad, Arezou and Pejman Firoozbakhsh. “Earliest Manuscript of Persian Verse, from Afghanistan”. The Invisible East Blog, 3 September 2020.

Davis, Dick (tr.). Abolqasem Ferdowsi. Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings. Penguin Books, 2016.

Editors, “Jamšid”. Encyclopaedia Iranica, available online.

Firoozbakhsh, Pejman. “Dast-Nivisht-i Qaṣīda-yi Fārsī az Hudūd-i sāl-i 400 AH” [Manuscript of a Persian Qaṣīda from about the Year 400/1007]. In Bi yād-i Īraj Afshār, edited by Jawād Basharī, vol. 2. Tehran: Duktur Maḥmūd Afshār, 1402/2024, pp. 661-72, available online.

Firoozbakhsh, Pejman. “A Panegyric Poem”. The Invisible East Blog, 12 December 2022 (in Persian).

Shaked, Shaul. “Yima in a Newly Discovered Manuscript”. In Arj-e-Xirad: Papers in Honour of Professor Djalal Khaleghi-Motlagh, edited by F. Aslani and M. Pourtaghi. Tehran: Morvarid, 1396/2018, pp. 21–28 (English section).

Shapur Shahbazi, Alireza. “Haft Sin”. Encyclopaedia Iranica, available online

Yastrebova, Olga. “A Panegyric Poem dedicated to Abū al-Ḥasan Siman-Tov”. In Life in Medieval Khorasan: A Genizah from the National Library of Israel. Exhibition Catalogue. St Petersburg, 2019, pp. 40-47, 132-5.

Zeini, Arash. “Interreligious Dialogue in Medieval Bamiyan”. The Invisible East Blog, February 2023.

About the author

Nabi Saqee is a Research Associate in the Invisible East Programme.